<!– –>

<!– –>

<!– –>

<!– –>

<!– –>

<!– –>

By Summer Jarro | December 18, 2017

<!– –>

For most of us, insulation is a given in our home or apartment. We wouldn’t want to live without the basic material that keeps warm air in and cold air out in the winter, vice-versa in the summer. But many low-income residents do.

“It’s like the difference in pouring a hot drink in a glass versus if you had an insulated mug or some of those thermoses that can keep liquids hot or cold for many hours,” said Lynn Jarrett, an engineer with the University of Florida’s Program for Resource Efficient Communities (PREC). “That’s the insulation preventing the heat from moving either outside in or inside out.”

UF’s Wendell Porter, who teaches energy courses and helped found Gainesville’s Community Weatherization Coalition (CWC) that performs free energy audits for low-income residents, says of all the efficiency standards debated locally and statewide over the years, attic insulation would go farthest to help the poor and save energy.

Just trying to be comfortable and survive in your home, you’re likely going to have higher utility bills.

Florida residences are required to have a heating system, but not an air conditioner or insulation. Due to changes in building codes over the years, new homes must meet minimum energy efficiency standards, including at least “R19” insulation, R being the resistance to heat flow. “The bigger the number, the better,” Porter said. “The Department of Energy for our state recommends between R30 and R38.”

Yet, some older homes, including rental properties, have no insulation whatsoever, and “there’s nothing against that,” Porter said. Advocates have tried for years to lobby for minimum insulation standards for existing houses and apartments locally and at the state level, but the real estate industry has fended off the change as too restrictive and costly.

Local advocates for the poor and for energy conservation say insulation is just one change that would go a long way toward helping low-income families, especially renters, deal with bills they can’t afford. The problem is generally with older homes that predate efficiency standards.

“Buildings that are being built now are significantly more energy efficient,” said Jason Fults, an instructor at Santa Fe College and sustainable energy advocate.

Older rental properties sometimes lack efficient appliances or even basic insulation because of what’s known as the “split incentive” problem: Landlords have no incentive to make upgrades because they aren’t the ones paying the utility bills. Renters may not be in the home long enough to recoup the investments, which they probably can’t afford anyway.

“Hence, neither party has a really strong incentive to make the investments in energy efficiency,” Fults said. “So what you end up with is rental housing stock that is on average less efficient than homeowner-occupied housing stock.”

For low-income residents, the split incentive can lead to not only poor living conditions and high utility bills, but a basic lack of comfort, Fults said.

“Just trying to be comfortable and survive in your home, you’re likely going to have higher utility bills,” Fults said.

“Do things the right way”

Some Gainesville landlords argue such upgrades mean they would have to raise the rent, which hurts low-income residents in the long run. Others have found investing in efficiency pays off; tenants with reasonable electric bills ultimately will have more financial stability.

When Betty Hopper bought a three-unit property near NE Second Street and NE Seventh Avenue in downtown Gainesville seven years ago, it was “a pretty big mess.” She wanted to make the property energy efficient even though it wasn’t required.

“You should do things the right way,” Hopper said.

She added insulation and a tankless water heater to all the units, and rooftop solar panels for the smallest. The changes have lowered her tenants’ utility bills significantly, Hopper said. The 1,100-square-foot downstairs bill has dropped from the $200, $240 range to “never more than $100.”

While the investment cost her, the changes have paid off in tenants who can juggle the rent and utilities and want to stick around.

“It’s a long-term strategy,” Hopper said. “There’s no cost in the long term doing that stuff.”

Local action

In addition to grassroots efforts such as CWC, city-owned Gainesville Regional Utilities has a suite of programs, including free energy surveys, to help poor families shore up their homes.

The problem is GRU’s programs that save customers the most energy and money – such as the Low-income Energy Efficiency Program that installs attic insulation and even efficient air conditioning – are for homeowners. But some of the properties most desperately in need of such upgrades are rentals.

GRU staff are among those who’ve proposed the city require minimum attic insulation and minimum energy efficiency standards for rental housing, without success.

In the past few years, local groups also have come together to try and help forge policies or incentives to make Gainesville rental properties more energy efficient.

In 2015, members of the sustainable energy organization Gainesville Loves Mountains, along with faculty from UF’s Levin College of Law, drafted a “Model Energy Conservation Ordinance for Florida Communities” with minimum energy standards for rental properties.

Basic rental efficiency requirements would help with the split-incentive problem, leading to energy savings and lower bills, Fults said.

The group researched conservation ordinances in three different cities: Berkeley, California; Boulder, Colorado; and Burlington, Vermont.

The model ordinance, created with Gainesville in mind, would be “a minimum housing code, providing minimum standards for all structures in the community in question where the property owner does not supply utility services.” According to the draft, property owners of older homes would essentially have to be in compliance with the 2010 Florida Building Code.

“You’d create a level playing field,” Fults said. “All the landlords would have to meet these basic certain standards, and so, it leaves more fair competition.”

However, initial conversations with city of Gainesville and Alachua County commissioners didn’t gain traction. Fults said he hopes the proposal could at least be debated.

Demonstrating success

In 2015, a group of Florida university researchers from UF’s Public Utility Research Center and PREC, along with the University of Central Florida’s Florida Solar Energy Center, set out to study low-income energy challenges on a large scale – in multifamily apartment complexes. They created the Florida Multifamily Efficiency Opportunities Study.

The researchers found that about half of all multifamily units in Florida were built before 1980, which meant dr

amatic potential for energy and water savings from retrofits. Applied to all the rental units in the state, the savings alone could provide electricity to more than 300,000 Florida homes for a year – and water savings of nearly 90 million gallons a day.

Of eight recommendations, the state adopted only two due to limited funding and not all of them being policy related, said Aaron Keller of the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, which commissioned the study.

Both recommendations involved pilot projects to see how dramatic a difference retrofits could make. The agriculture department’s Office of Energy chose Robinson Village, a 1986 property catering to mostly low-income families with children in Palm Beach County, and Crystal Lakes Manor, a 55-plus rental community built in Pinellas County in 1999.

Both properties received $500,000 of American Recovery and Reinvestment Act funds to retrofit as many units as possible, said Angela Clute, special projects manager with the Pinellas County Housing Authority.

Units in the worst condition were retrofitted – 84 in Robinson Village and 236 in Crystal Lakes Manor – since there wasn’t enough funding to do them all, said Jennison Kipp Searcy of UF’s PREC and one of the study’s project managers.

Both properties had energy efficiency upgrades to lighting, attic insulation, water heaters, ventilation ductwork, and central heating and air-conditioning systems. Crystal Lakes Manor also had upgrades to its ceiling fans.

Crystal Lakes saw energy use drop about 13 percent. Robinson Village, with larger units, saw about a 30 percent decrease.

The decrease at Crystal Lakes Manor saved residents an average $94 per unit per year, with an annual savings of $22,197 for the complex. At Robinson Village, the decrease saved residents an average $480 a year, with an annual savings of $40,308 for the complex.

While the tenants have lower utility bills, the landlords’ benefits are long-term. Owners at both properties have benefitted from reduced maintenance calls, said Sergio Alvarez, chief economist at the agriculture department’s Office of Policy and Budget.

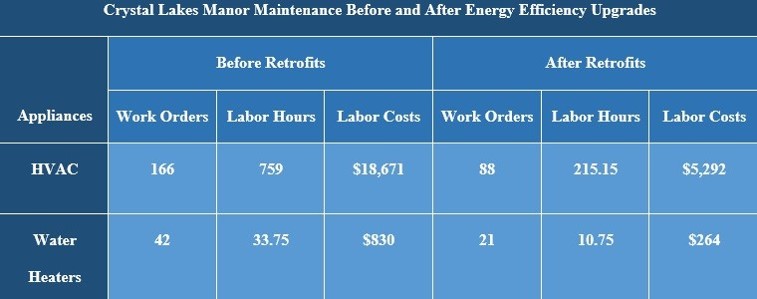

For example, the year before retrofits to efficient heat and air units at Crystal Lakes, management had 166 work orders for repairs and replacements that required 759 labor hours and $18,671 in labor costs. The year after the retrofits, the work order dropped to 88, labor hours to 215.15 and labor costs to $5,292 creating a savings of about $13,000 in labor costs alone. The upgrade in water heaters, meanwhile, dropped the work orders from 42 to 21, labor hours from 33.75 hours to 10.75 hours and labor costs from $830 to $264, Clute said.

Knowing the payoff for landlords is key, the policy researchers say. Many owners are unaware of the cost savings they could reap, so they’re apprehensive about retrofits, Clute said.

“The fact that now we have a lot more data for two big properties is a huge win,” Searcy said. “Being able to share the lessons learned and being able to share the stories can go a long way in helping promote policies that will then provide more incentives to the property owner to make these changes.”

The original study is in the hands of the Florida Legislature, which hasn’t taken action so far, Searcy said. A final report of the pilot results has not yet been published.

Home by home and program by program, ultimately it will take showing the savings possible to help the many renters struggling to pay their utility bills in Florida, Searcy said.

“To see that gap between the people who can afford and have an easy time paying their bills and those who are relying on the property owners to make the investment, to reduce that cost burden, to see those numbers shrink rather than continue to grow, to see a reversal of that trend ultimately would be fantastic.”

Up next: State of Emergency »

<!– –>

Special Report from WUFT News

Special Report from WUFT News