<!– –>

<!– –>

<!– –>

<!– –>

<!– –>

<!– –>

By Liana Zafran | December 20, 2017

<!– –>

In the early years of the 21st Century, Gainesville was considered one of the most progressive U.S. cities on solar energy, outshining other municipalities in programs and capacity. As part of its goal to slash carbon emissions, the city was first in the nation to offer feed-in-tariff rates – paying solar customers to send surplus energy back into the grid. Other incentives likewise brightened the landscape, giving the city one of the highest rates of solar generation per customer in Florida.

But a closer look at solar generation in Gainesville shows how that story misses low-income neighborhoods. Like underground power lines and highly efficient homes, solar coverage is settling into a familiar pattern: fewer solar systems are installed in low-income neighborhoods most in need of the lower utility bills and other benefits.

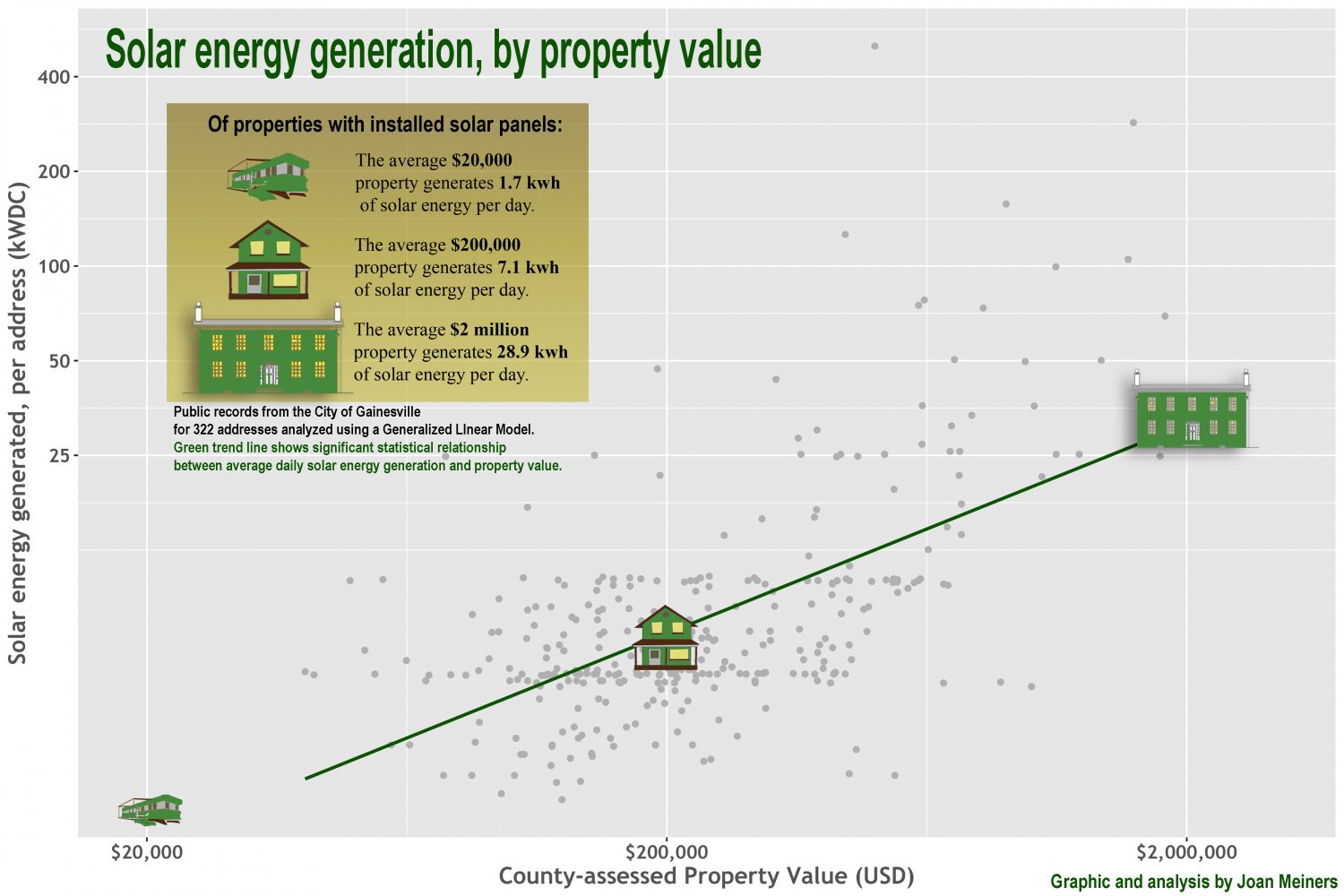

An analysis of solar generation in Gainesville shows the strong correlation between solar generation and higher-value properties, reflecting not only more expansive roofs for larger solar panels, but the ability of wealthier homeowners to invest, access rebates and loans and benefit from tax credits.

“Florida might be the Sunshine State, but solar follows the money not the sun,” says Barry Jacobson, owner of the Gainesville-based solar contracting firm Solar Impact.

No one would benefit more from solar than low-income consumers, who pay a higher portion of their income on utility bills, according to a report from the Clean Energy States Alliance (CESA). But poverty is a considerable barrier: Low-income residents lack the savings to buy solar systems, may have low credit scores that impede financing, or are renters. Bringing solar coverage to low-income neighborhoods requires up-front investment, which is difficult with squeezed local budgets. While the average cost of solar panels continues to drop, a 5-kilowatt system can cost roughly $15,000.

Wendell Porter, a UF professor who specializes in sustainable energy, said shoring up inefficient homes is the most-logical first step for reducing the energy burden for the poor. Meanwhile it may not be cost-effective to install small solar arrays on small rooftops. But once residents’ homes are efficient and secure, Porter says, community solar might be a good option.

Community solar, sometimes known as a solar garden, is one way other parts of the country are bringing solar power to poor communities, turning the energy burden into an energy benefit. New York state, for example, has required 20 percent of customers in its initial community solar projects to be low-income.

Federal energy assistance programs such as the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program are also starting to include solar. In some parts of the country, Habitat for Humanity is beginning to build solar homes. The CESA report finds that installing solar on public housing could save taxpayers some of the $5 billion that the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development spends annually on utility bills. Affordable solar housing programs in California led to as many installations in low-income neighborhoods as in high-income neighborhoods by 2015.

Washington D.C.’s Sustainable Energy Utility has installed more than 350 solar panel systems on low-income homes over the past five years in a program that aims to lower electric bills by some 70 percent.The installations are financed by a surcharge on all electric and natural gas ratepayers. Ted Trabue, managing director of the D.C. Sustainable Energy Utility, describes the surcharge as a “public benefit” that helps the district meet its carbon-reduction goals, ease the burden on the poor and strengthen local business. “Here’s an opportunity that the government has to actually create economic development and economic opportunity in a confined area,” Trabue says.

Gainesville simply doesn’t have the political will to charge ratepayers any more than they already pay, says Mayor Lauren Poe.Gainesville Regional Utilities’ rates are among the highest in Florida. Meanwhile the city’s purchase of the controversial biomass plant has left some taxpayers leery of new projects.

Poe says he’d like to see Gainesville tap deeper into programs such as federal Property Assessed Clean Energy (PACE), which allows a property owner to finance improvements without a large up-front cash payment. “For a low-income family, if you can spread out the cost of installing solar over 20 to 25 years of their annual tax bill, then that becomes incredibly affordable,” Poe says.

The CESA report stresses that it will take a blend of approaches including community involvement, such as volunteers who can bring solar to existing anti-poverty and housing programs like Habitat for Humanity. Jason Gonos, a local solar expert and co-owner of Power Production Management, agrees.

“The public has to be involved and people have to care because then it’ll start to trickle up to politicians,” Gonos says. “A solution would be for the city to implement an equitable goal and to incentivize local businesses to take part in that goal, so that businesses can pick up the torch and lead the charge.

“Gainesville could be an oasis” says Gonos. “A place that both the north and south look at for its solar equity.

Up next: Tiny Houses, Big Hurdles »

<!– –>

Special Report from WUFT News

Special Report from WUFT News