By Taylor Mayer | May 22, 2023

Taylor Mayer joins the set of the “First at Five” newscast – on WUFT-TV, the PBS affiliate for north central Florida, on April 17, 2023 – to tell about the UFxFAMU1963 reporting experience along the U.S. Civil Rights Trail. (WUFT News)

I was raised in a predominantly white, Jewish area in Miami Beach that values community-minded beliefs, sheltered and blessed, and only rarely confronted with any forms of bigotry but for the occasional antisemitic slander here and there.

Sure, my parents taught us to never judge and to embrace all people the same, regardless of race, ethnicity, religion or sexuality. Sure, I went to public schools and learned about the transatlantic slave trade, Jim Crow and many of the infamous and heinous acts against Black Americans. Yet, it never really affected me. The Black struggle always felt like a far-removed issue that another minority encountered, not something that I ever needed to otherwise consider.

And then the inevitable happened. 2020 became the year of political and social unrest, with the rise of yet another Black Lives Matter movement and a call to, yet again, end racial discrimination. Even so, it seemed to be a cultural war that highly unaffected me. That’s not to say my heart didn’t break for the innocent lives lost to deep-rooted hatred. The words “systemic racism” first came to my attention during this time. Even then, I took anyone calling my beloved America a breeding ground for hatred and intolerance as attacking me personally. I found myself blindly defending an America I frankly did not know much about when it came to race relations.

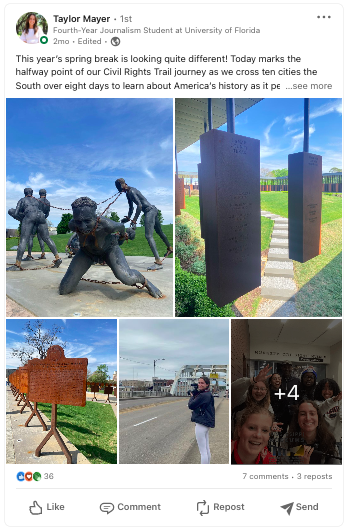

Therefore, the opportunity to venture on an eight-day class trip across the South to learn about the Civil Rights Movement was one I enthusiastically welcomed. Aside from the journalistic duty, I viewed this expedition as a personal journey, one to put myself out of my comfort zone, learn about true Black history – not the textbook version – and immerse myself in the struggle for which people put their lives on the line.

As our required class reading of “The Race Beat: The Press, the Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation” evolved, I found myself becoming angrier. How were people complacent at a time others were lynched for nothing more than having a different skin color? How were people so cruel and encouraging of that same cruelty? How were these hate-riddled humans the leaders of our nation? Why did it fall on the Black Press to report on what was actually happening? How was this my first time hearing about Medgar Evers or the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham? Although I retained hope that not all people were evil, this evil seemed to get a hall pass over and over. Pride washed over me each time I learned about a Jewish journalist who reported the truth, a Jew that participated in the movement, or Jews in positions of power who used it for good, like those who helped to create the NAACP.

Marvin Nichols, of Atlanta, shares his perspective at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, as someone on a civil rights trail journey of his own. (Taylor Mayer/WUFT News)

Our class trip to St. Augustine, one Monday in February, also opened my world. It soon became apparent this wasn’t just Black history as a separate story – this was American history. A history all Americans need to learn more deeply. I had visited St. Augustine many times before, often for a beach day with family and/or friends. Yet I was never aware of the significance it played in the Civil Rights Movement. I found myself asking more questions, engaging afterward in dialogue with friends and confronting my personal bias.

As our spring break trip approached, I became aware of the intimidating task of teaching myself American history, with a microscope on the South and the way the Black community was affected. While it seemed daunting, I was up for the task. I was happy to meet our accompanying students from Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University (FAMU) in Tallahassee, and immediately knew we would form a bond. Aside from our different backgrounds, we were all there to accomplish a personal goal. Our first conversation on our 15-seat van was eye opening. Some of us wanted to see America in its rawest form, some wanted to learn about ancestors who were on those first few ships from Africa, and others wanted to understand why racism still has such a tight grip in 2023.

The second stop – The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, in Montgomery, Alabama – hit me like a truck. Disillusioned by what I had been taught my entire life, I was left with a void only to be filled with more questions and more answers. My prior understanding was that Black history started with slavery and ended with the Civil Rights Movement. How was I so wrong? Lynchings were still happening in the ‘80s? I met a Black couple who, when reading over the lynching plaques in the memorial, shared a compelling sentiment: “That could have been me, just in another time period.” I often felt the same when visiting Holocaust museums, tears welling in my eyes. As three seemingly completely different people, we were at the same place in the same point in time, counting our blessings we weren’t born 80 years earlier.

Also early in our journey, a sobering discovery came upon me that persisted throughout the trip. Aside from my Jewish identity, I have never found my white appearance to brand me as a minority. Each time I walked into shops and restaurants as one of the few white customers. I found myself behaving even more respectful, not just because I was in the South, but because I wanted to show that I was “not like the rest of them.” While I will never know what it is like to be Black in America, this gave me, well, perhaps at least one toe in a Black person’s shoe.

Taylor Mayer recounts her experience after she and her advance journalism class travels from Gainesville to St. Augustine to learn about its civil rights history. (WUFT News)

In my trip journal, I recounted that “I feel like slowly my preconceived notions are shedding away and it feels shocking.” A notion from a former Mississippi official struck me: If you drained all the rivers in the state of Mississippi, how many bodies would you find? This eerie feeling followed me everywhere, an inescapable thought about the rest of America. What about Alabama and Arkansas, even Florida? The van served as a haven to reflect and drive through each city with a certain disconnection. At any second, I could escape this harsh history, in stark contrast to those for whom it was their everyday reality.

As the days passed, the bonds between our group strengthened. One of the girls confessed that I was the first Jewish person she had ever met. Another confided in me that she rejected her religion because of its views on her homosexuality. Another friend and I discussed our similar journey in finding G-d in our respective religions. Regardless of our personal circumstances, it was apparent that we all endured struggles, the same as the next.

On our final day, in Atlanta – during an interview in front of the gravesites for the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King – a Black woman from the Netherlands accused me of not having a tie to Black historical sites because of my skin color. For 10 minutes, she said I would never understand the struggle of Black people, that I live life privileged, and to never ask a Black person what they hope to get out of visiting these sites. After a week of strangers appreciating my willingness to share their stories, she was judging me solely based on the color of my skin. My curiosity and work I had done up to this point felt invalidated. What irony?

I’m reminded of a sign from decades past that we saw in a museum: “No Negroes, No Jews, No Puerto Ricans, No Mexicans.” Olivia White, a civil rights activist who we met in Birmingham, shared that while our skin colors are different, we all have red blood. Due to our journey, I have learned that the Black struggle is not something I can just ignore simply because it does not affect me firsthand. It is impossible to remove myself. I am in a position to educate those around me, take an active part in the making of history happening around me, and serve as an ambassador for positive change. In doing so, I’m hoping everyone will agree that we’re all in it together.