A special report from WUFT News

and the UF College of Journalism and Communications

Peak Florida

Florida’s population growth has rebounded since the recession — now back to nearly 1,000 people a day like in the ’80s, but with weakened development regulations and accelerating climate change. Our special report examines the state’s latest growth wave, and whether we can welcome newcomers without losing what makes Florida, Florida.

Meet some of the state’s heritage citrus families trying to preserve Florida’s signature crop; St. Johns County residents working to save coastal wetlands and a historic island that may contain the graves of enslaved Africans; and Central Floridians hoping the region can be a model for smart growth, letting bears and other wildlife keep their homes amid cities full of ours. Finally, read about solutions to growth-related messes like water-pollution and traffic gridlock that will also help Florida prepare for the rising seas and storms ahead.

(Illustration by Jerald Pinson)

Florida’s Growth: A Cliffhanger

Data story and graphics by Joan Meiners

Florida is booming.

Data from the University of Florida’s Bureau of Economic and Business Research show the state now growing at a rate of 919 new people a day. With weakened development regulations, combined with sea rise and more-severe storms predicted by scientists as temperatures warm, how will Florida manage its growth?

The state’s population has doubled since 1980.

1980

1990

2000

2010

2018

While rising seas shrink its land.

As sea rises and the coast becomes more hazardous, Florida will have less and less space for its growing population and native wildlife. A recent report by Climate Central used FEMA flood maps and sea rise projections to find the cities most at risk from coastal flooding by 2050. Nine of the top 10 were in Florida.

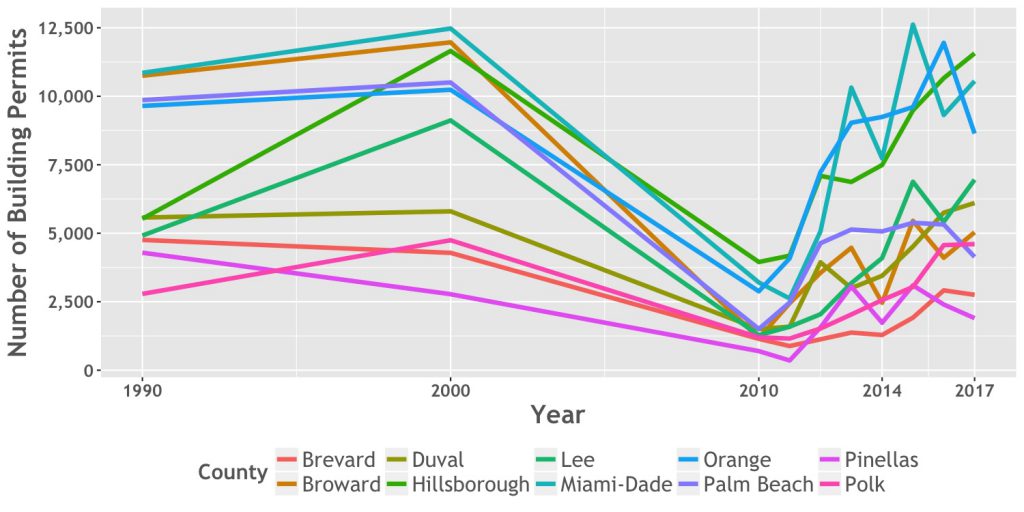

Development continues apace.

Ten years after the housing crash of 2008, Florida’s market has rebounded. Housing permit numbers from the Enterprise Florida Data Center show the number of housing permits issued in Florida’s 10 most-populous counties is approaching pre-crash numbers. Some financial advisors warn of another reckoning.

New-home construction remains just as vigorous in flood-prone areas.

Despite the science showing the pace and path of sea rise, development is proceeding in flood-prone areas at a slightly higher pace than in safer regions, according to an analysis by Climate Central and Zillow. The report found 908 new Florida homes – together worth more than $1 billion – built in areas likely to flood by 2050.

Intensifying storms drive migration.

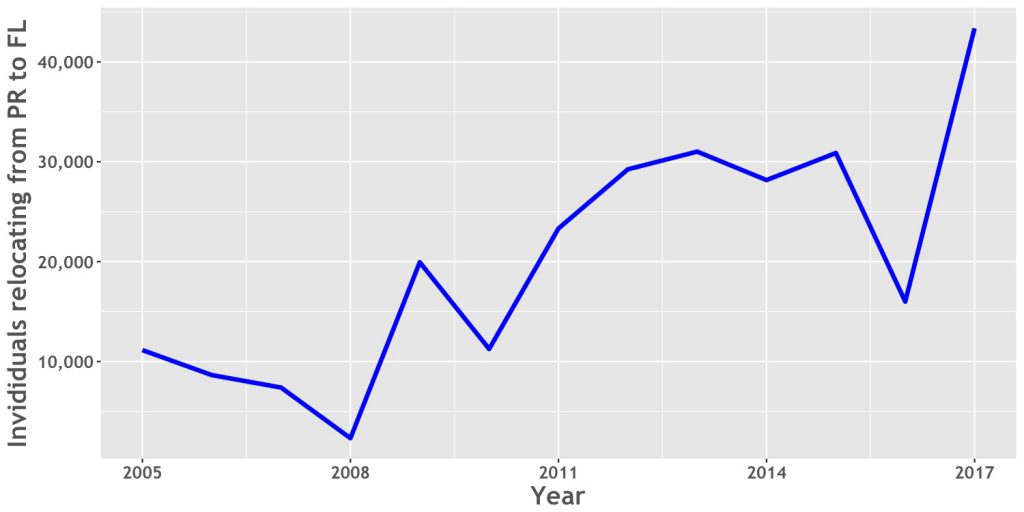

Scientists say climate change is aggravating the impacts of hurricanes and other tropical storms. In 2017 after Hurricane Maria caused widespread destruction on the island, thousands of Puerto Rican Americans were forced to flee to the mainland.

Data from the UF Bureau of Economic and Business Research show more Puerto Ricans arriving and staying in Florida in 2017 than in any other year since 2005. Amid more-severe storm impacts, Florida could see more migration from Caribbean islands – until Floridians become the ones forced to move.

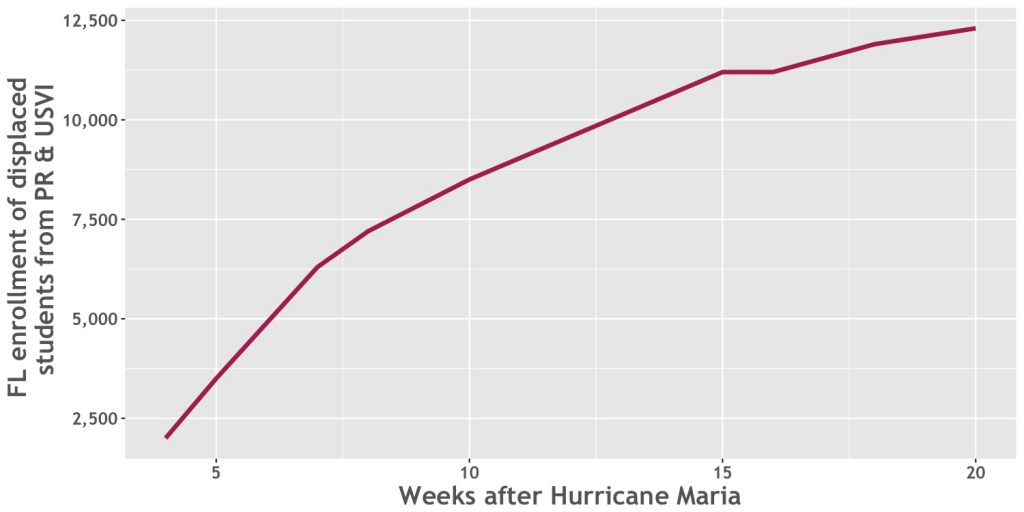

Schools are overwhelmed.

Schools are struggling to accommodate the new influx of students, both from steady increases in state population and sudden ones caused by catastrophic events. Hurricane Maria added approximately 12,500 students from Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands to Florida’s public school system.

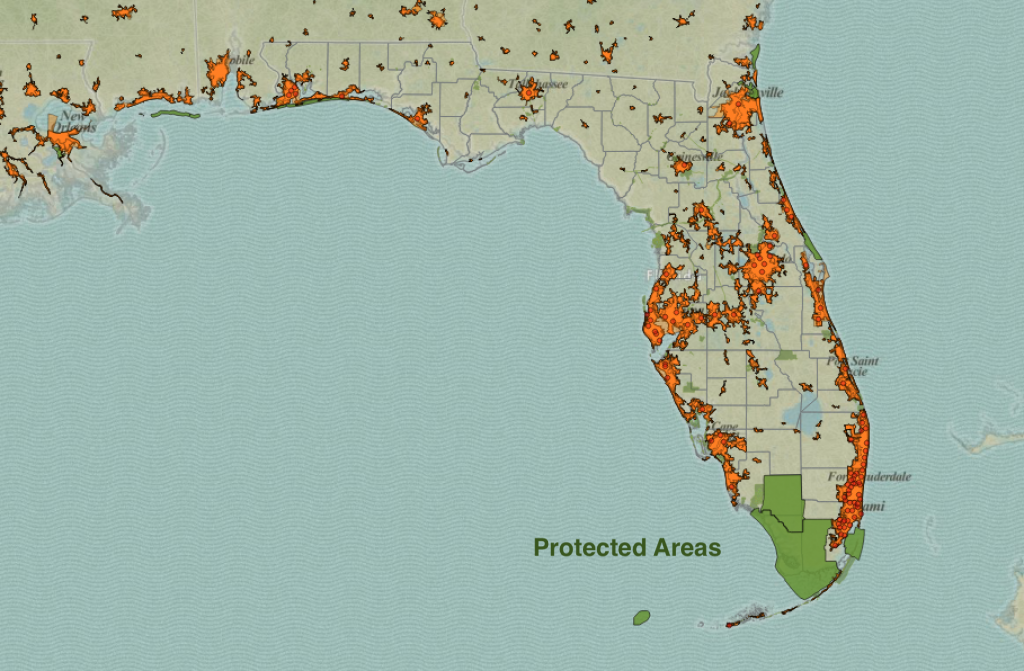

Florida’s wildlife is at risk.

Increasing development risks cleaving habitat and migration corridors used by bears, panthers and other wildlife. Each hour, about 20 more acres of rural Florida are lost to development, according to the Florida Wildlife Corridor project. With strategy, wildlife scientists say some 15 million key acres could still be protected in support of biodiversity and ecosystems.

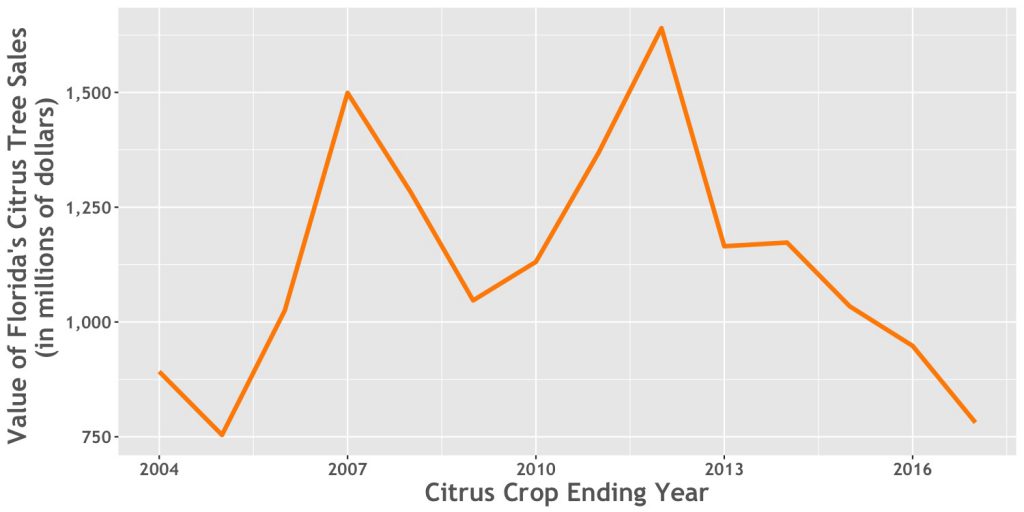

Crops give way to rooftops.

Urban development is also squeezing out Florida’s signature crop as citrus greening makes it harder to farm. Florida’s orange production decreased 16 percent to 68.8 million boxes in 2017, according to the Florida Department of Agriculture. Grapefruit was down nearly 28 percent to 7.76 million boxes.

What happens next is a wildcard.

For now, scientists expect population to continue to grow. But as seas continue to rise, Floridians could begin to leave the coasts for interior Florida — or leave the state.

The problems of growth and sea rise could compound and the great Florida in-migration could flip.

When scientists combined Florida’s projected population growth with future impacts of sea rise, they found that far more people – between 1.2 million and 6 million – could be displaced from coastal homes as soon as 2100.

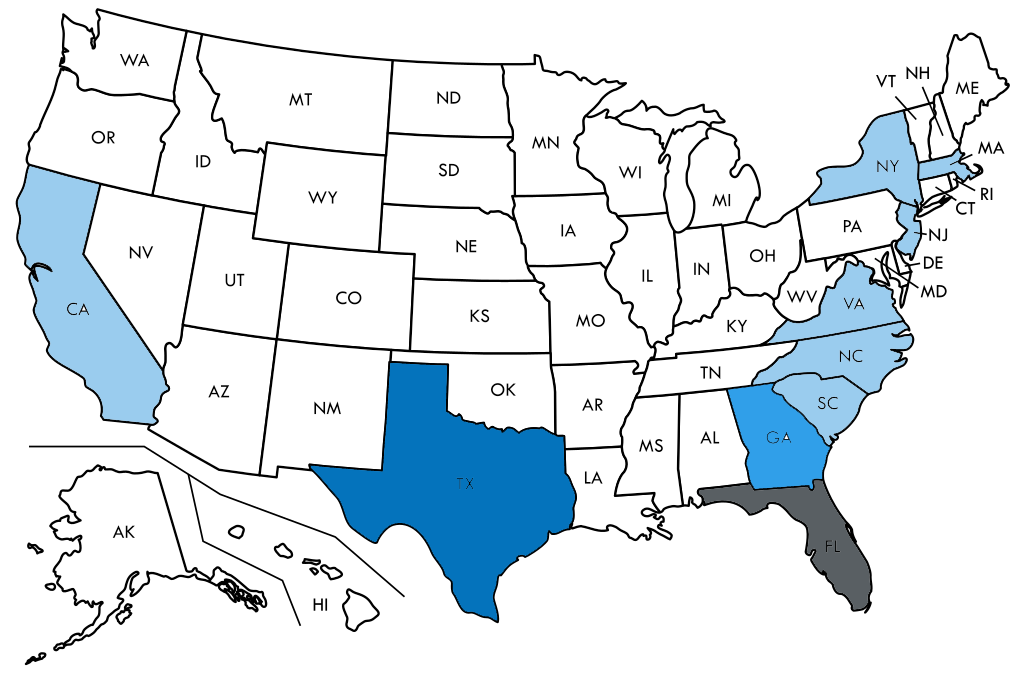

Many Floridians may leave …

By 2100, scientists Mathew Hauer, Jason Evans and Deepak Mishra found, up to 6 million Floridians may have to find other homes. They may head to Texas, Georgia, the Carolinas, Virginia, New York, Massachusetts and California.

Others may be left behind.

Could Floridians join the rising membership of climate refugees – people displaced by changing environments? Across the globe, those pushed from their homes often have the deepest local roots, with nowhere else to go and few resources to start over. But there is another choice.

Planning for a sustainable future can help.

Smarter growth is key. We can develop more-compact urban areas; plan to protect water and land; restore more coastal wetlands to create storm barriers; legislate to conserve wildlife corridors; and adopt transportation and energy options that accommodate 22 million Floridians with minimal pollution. But we will have to work together.

This is Peak Florida

Read our series on Florida’s growth pressures and the solutions at hand.

Peak Florida

Peak Florida