Evidence suggests enslaved African people may be buried on St. Augustine’s Fish Island, now eyed for luxury homes.

Florida oranges, depending on who you ask, represent varied histories. Some may know Florida supplies an outsized share of U.S. citrus. Others may know plantation labor kick-started citrus grove expansion. Even fewer likely know that if expedited development of Fish Island, where El Vergel plantation once operated, occurs then new luxury homes may bury human remains, unmarked graves, and other artifacts from enslaved African people who lived, labored and likely perished on the island.

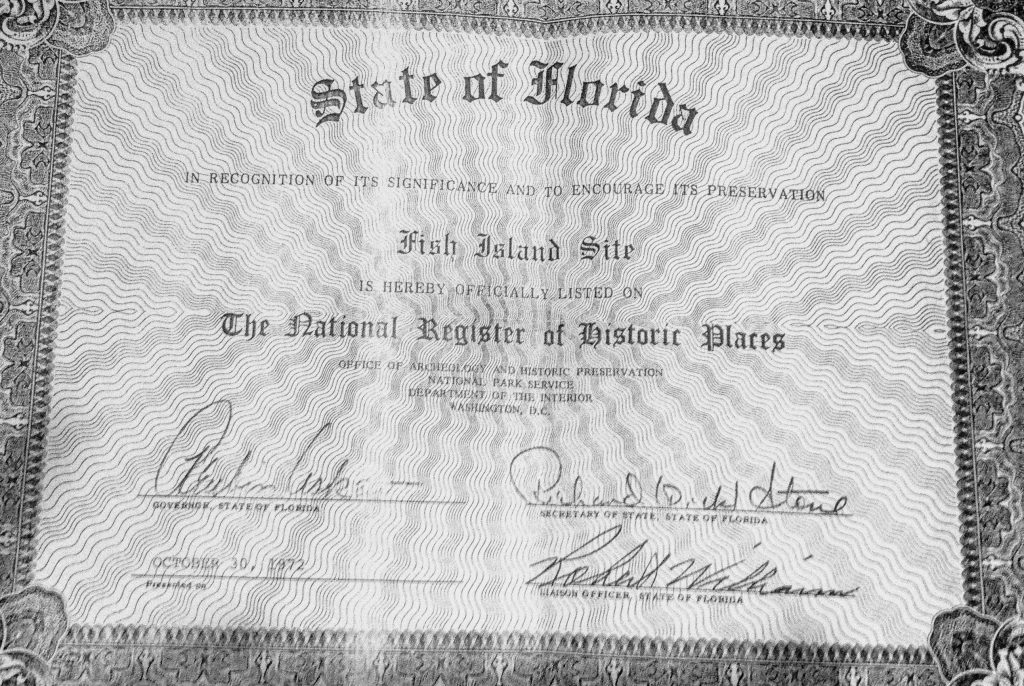

Named for Jesse Fish, the English Protestant settler from New York who once owned it and most of St. Augustine, Fish Island lies near the Matanzas River. It forms part of Anastasia Island, its estimated 72 acres annexed in sprawl.

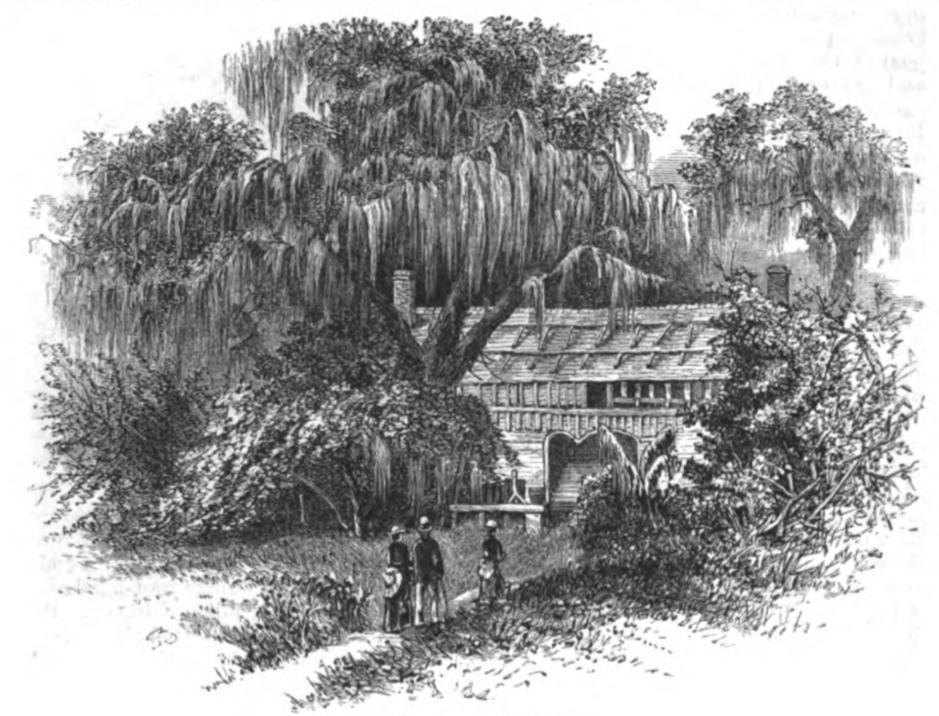

Born in 1724 or 1726, Jesse Fish later moved to St. Augustine as a child for work. About a decade later, he began trade with the city. Though he visited New York, South Carolina and Cuba, Fish maintained residence at his plantation El Vergel until he died there in 1790.

El Vergel, which means “the garden” or “the orchard,” fuels lore about Fish. In its heyday, plantation laborers produced globally lauded oranges, other citrus and “orange shrub,” an alcoholic beverage.

Fish Island riveted other colonial settlers. Andre Michaux, a French botanist, wrote praises after his 1788 visit to El Vergel. Michaux wrote that Fish’s oranges were succulent, large “and more esteemed than those brought from the West Indies.”

Of course, notable southern plantations did not run themselves. Enslaved African people, and sometimes indentured European people and captured Native American people, supplied the labor, despite sub-tropical heat and risk of infectious diseases. If Michaux’s time estimate — that Fish’s orchard had operated for 40 years by the time Michaux visited — held true, then Fish would have established El Vergel around 1750.

As Vanderbilt University historian Jane Landers wrote in her book Black Society in Spanish Florida, Fish introduced “most of the African-born slaves registered” in Florida between 1752 and 1763. Landers also noted Cuban records of these “slave imports” to Florida.

Visually, the record is jarring. One can consider whether the ubiquity of Fish’s name or his ownership of children ages five, eight and nine is more troubling. During this period, Fish is the listed owner of more than 100 African people.

Beyond those records, though, the Florida lives and fates of these African people is unclear. With gaps in the written and archaeological records, some St. Augustine residents have advanced cultural heritage and gravesite respect arguments in support of preserving the federally recognized property.

They hope city officials, a private landowner and a major home developer will consider whether irreparable harm will result if the community – proposed but uncertain — is constructed on the island.

These residents seek preservation of Fish Island as an archaeologically and environmentally significant site. They hope to inspire broader grassroots advocacy and knowledge of potential harm development could cause. At the same time, they are sensitive to not interfering with the developer’s contract given Florida jurors’ determination in a Stuart case earlier this year that a longtime environmentalist exceeded her free speech rights and illegally undermined a developer’s deal.

St. Augustine residents Susan Hill and Jon Hodgin have taken particular interest in Fish Island’s cultural preservation. The married, retired UF College of Medicine professors researched and wrote a text called “Fish Island’s Historical Past: A Citizen’s Perspective on What We Stand To Lose” to inform the community.

The work reflects concern that development of Fish Island may hasten Afro-erasure. “All parts” of St. Augustine history “are worthy of being told, recognized, and preserved,” Hill said.

This history includes a 1787 census, on which Fish reported 17 slaves, and several accounts that Fish owned, traded and managed many enslaved African people. The level of Fish’s slave ownership contributed to city archaeology experts’ statement: “it is probable that there was some mortality [on Fish Island].”

But, where? Whether enslaved African people died on Fish Island and, if so, the dispositions of their bodies, highlights colonial British and Spanish tensions. Modern Florida law also makes provisions for certain human burial sites.

In Black Society, Landers wrote that some Spanish Catholics in St. Augustine believed English Protestantism “infected” enslaved Africans. She also explained that some Black Catholics could be buried in mainland St. Augustine’s Tolomato cemetery, where Spanish, mixed race and other Catholics were often buried.

However, Fish was Protestant. Despite being bilingual (English and Spanish), his apparent Spanish cultural acumen and upbringing with a Spanish family, he did not “pass” for Catholic. To this point, as Hill and Hodgin wrote, “It [is] unlikely that he would have allowed his slaves to be baptized as Catholics.”

Where, then, would African, unbaptized, enslaved laborers for Fish be buried?

The city of St. Augustine balances its duties to respect private property rights with its obligations to protect archaeologically significant artifacts. An archaeological review at Anastasia Island, including parts of Fish Island, yielded a 2001 preliminary cultural resource assessment by archaeologists Andrea P. White and Carl D. Halbirt. They documented substantial findings, including evidence of Fish’s tomb, about 230 feet south of the main house, another tomb, and a wharf where “goods and people were transported across the bay [from the island] to St. Augustine.”

They listed standard “data recovery” steps for these kinds of cultural assessments of property, including visual examination for surface remains; a systematic shovel-and-auger survey to determine the extent of human occupation across the area; and testing of excavated units.

White and Halbirt documented “scattered artifact deposits” associated with a probable slave residence on Fish Island. Moreover, they noted, “the possibility exists for slave burials on the island, but their location is unmarked and unknown.”

Given El Vergel’s decades of operation under Fish, including when the plantation boasted a reported 3,000 mature orange trees, and laborers provided international shipments of goods, “some [enslaved African people] surely must have died there,” Hill and Hodgin wrote.

Anthropologist and St. Augustine native Marsha A. Chance has professionally supervised surveys of Anastasia Island and parts of Fish Island. Chance expressed a sense that African burials were possible on Fish Island, tempered by practical challenges of proof.

“We know he had slaves and he had a lot of them,” Chance said. Based on customs of the era, she asserted the unlikelihood that unmarked graves of the enslaved would be close to primary plantation buildings. If present, slave graves, she said, would “be at a distance from that area.”

During a city planning and zoning board meeting in August, Chance was among about three dozen residents who spoke in opposition to an application to rezone the site for 170 homes and neighborhood amenities. Chance also requested “ground-penetrating radar to search for additional human burial remains.”

Who may be there?

The 2001 White and Halbirt report suggested Fish underreported the number of enslaved Africans on his plantation and raised the possibility of mixed-race Fish descendant remains on Fish Island.

By 1790, Jesse Fish, who established El Vergel, died. Because Fish died in debt, his estate, which included enslaved African people, was auctioned to satisfy creditors, as Landers wrote.

Fish’s son, Jesse Jr., later bought back part of his father’s estate. Jesse Jr. fathered seven children with an Afro-descendant woman named Clarissa who some historians describe as Jr.’s slave or mistress. Others called her his “common-law wife.”

Yet, “what became of the plantation and its occupants” after Jesse Fish Sr.’s wife, Sarah, died, “is presently unknown,” White and Halbirt wrote.

For now, connections between Fish Island history and prospective African burials are conceptual, Chance said. “The idea that there would be a slave cemetery is something that has been reached by logic.”

Logic, she reasoned, would also provide that if enslaved Africans — who, like Fish, were Protestant and not Catholic — died on El Vergel that they would not have been brought by boat from Fish Island for burial in mainland St. Augustine.

But definitive proof would require more-sophisticated investigation. “I can’t say there’s any one person who has walked every inch of that property,” Chance said.

So, are enslaved African people in, on, or around Fish Island? Are Fish descendants, free mixed-race people of color, buried there? What now?

The City of St. Augustine, state of Florida and University of Florida have “gone to great lengths in forming alliances to preserve the history” of St. Augustine, a place “we all love so much,” Hill and Hodgin wrote.

Those alliances produced UF Historic St. Augustine Inc. (UFHSA). In its articles of incorporation, the non-profit lists preservation, restoration and maintenance of “historical” landmarks, sites and remains in the St. Augustine area as reasons for its existence. That founding document further provides that UFHSA may “solicit, raise, accept and receive” grants, gifts and other property to support cultural and archaeological preservation in and around St. Augustine.

Given Fish Island’s location in and significance to St. Augustine, resolution of this challenge presents a special opportunity. The same trifecta that produced UFHSA could marshal its economic, intellectual and political resources to proffer sensitive alternatives to development.

Timely and equitable action for Fish Island would, as Hill and Hodgin said, let those who may be there “rest undisturbed in this place.”

Peak Florida

Peak Florida