America’s largest homebuilder proposes developing one of the last private-owned wild swaths in coastal St. Augustine.

Fish Island photograph courtesy Walter Coker

Perhaps it was a miracle that Fish Island survived the Spanish conquest of the 16th century. No cannons, colonies or conquistadors landed on this humble stretch of forest nestled alongside St. Augustine’s 312 bridge.

And perhaps it was another miracle that Fish Island survived the British buccaneers of the 17th century. In the midst of revolution, turmoil and political uncertainty, this 72-acre island of pine trees, eagle’s nests and wetlands remained unscathed by the series of raids and pillaging that marked the history of America’s oldest European settlement.

Then came the 18th century, when part of the island was developed as a citrus estate by a settler named Jesse Fish. Ultimately, nature took back the once-famed orchards and a plantation house.

But like many of Florida’s remaining forests and wetlands, Fish Island’s luck may be running out amid intense urban population growth in the 21st century. The largest homebuilder in America, D.R. Horton, has plans to develop the slim peninsula that also serves as a barrier to rising seas — and may hold archaeological evidence of enslaved Africans in a city that has done so much to preserve its Spanish heritage.

Company officials presented their proposal to St. Augustine’s Planning and Zoning Board in July. The development plan initially included 170 single-family housing units, two roadways and an amenity center.

Here’s what one segment of the Fish Island parcel might look like developed, compared to recent satellite imagery. Slide to compare.

After the initial request was denied because of a disagreement in Florida zoning codes, the company proposed an altered planned unit development (PUD) to the board in August. In what city staff described as “the highest attendance in the board’s history,” more than 100 citizens voiced their concerns about D.R. Horton’s plans.

The board unanimously denied the PUD application. And now, the company’s 30-day window to appeal has lapsed. Still, St. Augustine citizens are in the dark about the fate of Fish Island.

At 28, Jen Lomberk has helped lead the charge to save Fish Island from development, pushing against daunting trends: The third-fastest growing county in Florida, St. Johns County is also one of the fastest-growing in the nation, according to the U.S. Census.

“It’s completely understandable that people want to live here,” Lomberk said. “But our goal is to promote smart, sustainable development as opposed to irresponsible building.”

As the Matanzas Riverkeeper, Lomberk has a strong appreciation for water quality. Most of the threats and pollution found in the Matanzas are directly tied to urbanization and development, she said. So, she’s traded her daily routine of oyster gardening and educating children for an aggressive social media campaign informing the public on the importance of conserving Fish Island.

“The first thing that people see when they cross into our island shouldn’t be a bunch of D.R Horton houses,” Lomberk said.

Jim Young, president of the Young Land Group and current owner of the Fish Island property, declined to elaborate on the company’s next steps. His staff, and other owners of the property, will field no interviews until January at the earliest, he said. D.R. Horton representatives also declined to comment on the future of Fish Island.

St. Augustine City Commissioners who would ultimately decide on whether the development can proceed have been notably quiet on the matter.

The majority of the county commission, not bound by political obligation in the island’s fate, have voiced support for conserving Fish Island. Options to turn the land into a park, boat ramp or conservation site have all been discussed.

Not only would the projected development be an eyesore, Lomberk said, but it would have considerable environmental impact. It also seems to defy wisdom on coastal resilience in the face of rising seas.

According to Federal Emergency Management Agency flood standards for St. Johns County, all development must be built 9 feet above sea level. Fish Island, and most of the surrounding peninsula, sit at around 4 feet, according to a survey by Gulfstream Design Group engineer Matt Lahti.

If its plans are approved, D.R. Horton would have to clear and fill the grassy parcel because it’s so low, Lomberk said. Fish Island’s plant and animal life would suffer, and long-term, St. Augustine would lose yet another buffer between development and rising seas.

“There’s several places in the county that have been built in such low-lying, vulnerable places now that millions of dollars are being spent to retrofit the infrastructure,” Lomberk said. “People want to be close to the water, but we’re building on a lot of the property that is most vulnerable to sea level rise.”

At the plan board meeting this fall, former St. Augustine Beach Mayor Gary Snodgrass pointed to the beach town’s move to buy land for Ocean Hammock Park as a way local government can protect from over-development, preserve wildlife and better prepare for sea-rise. That project was funded with a grant from the Florida Communities Trust Fund.

Advocates also suggest that Florida Forever, the state’s public-land acquisition program, could be one source of funding to purchase Fish Island from its owners and preserve the land in the name of conservation and climate adaptation.

“But first, the state needs to know what’s happening here,” Lomberk said, “The people want to keep Fish Island as the doorway to our community.”

It’s a brisk October morning, about 48 degrees with ocean salt mixed into the chilled air. A small group of seven activists hoist a tent at the local St. Augustine farmers market, awaiting the surge of shoppers.

Today, Susan Hill’s fight is just beginning.

Hill and her husband, Jon Hodgin, have worked tirelessly to put together a “Save Fish Island” campaign ever since she heard of D.R. Horton’s plans, she said. As the city’s population continues to rise, she has since spent hundreds of hours researching, studying and communicating the history of Fish Island.

“We’re a grassroots project made of ordinary people” Hill said. “But today, we’re here to preserve and conserve Fish Island.”

An expert on the land’s history, Hill has made it her mission to spread awareness on Fish Island’s historic past, she said.

“Most people we speak to haven’t heard the story of Fish Island, which exists only in bits and pieces dating from the 1700s to the present,” Hill wrote in a 17-page historical narrative she co-authored with her husband, entitled Fish Island’s Historical Past: A Citizen’s Perspective on What We Stand to Lose.

“Sometimes we don’t realize the value of something until we stand to lose it, forever.”

Hill’s home is filled with hundreds of historical documents she collected from the St. Augustine Historical Society research library. There may be enough evidence, Hill believes, to prove there are unmarked slave burials on Fish Island.

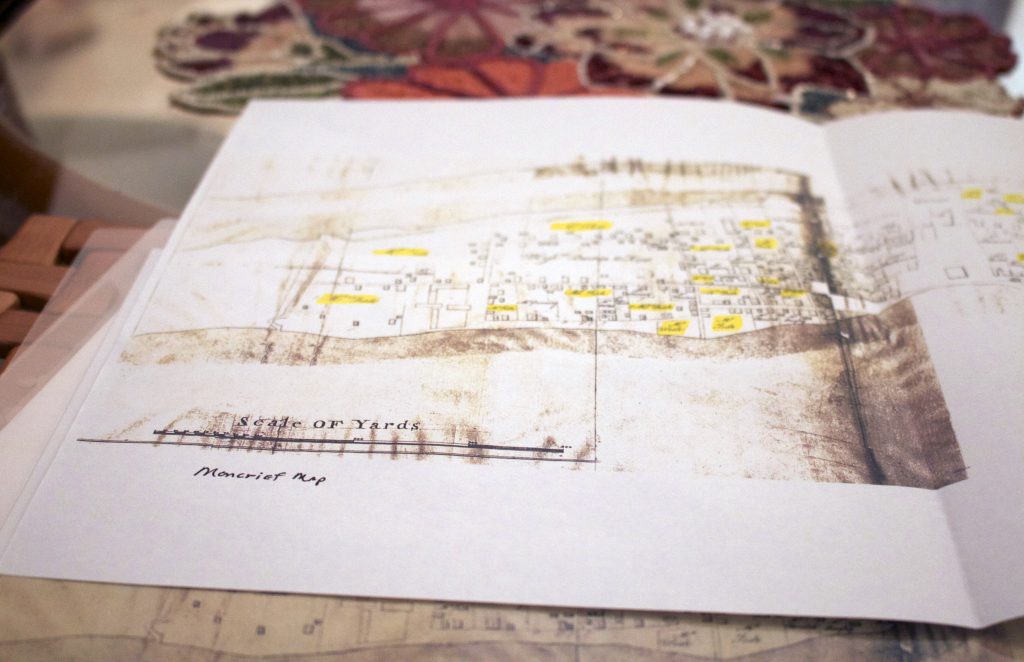

This map, one of Hill’s many documents on Fish Island. depicts all potential land owned by Jesse Fish in the 18th century. / Photo: Max Chesnes

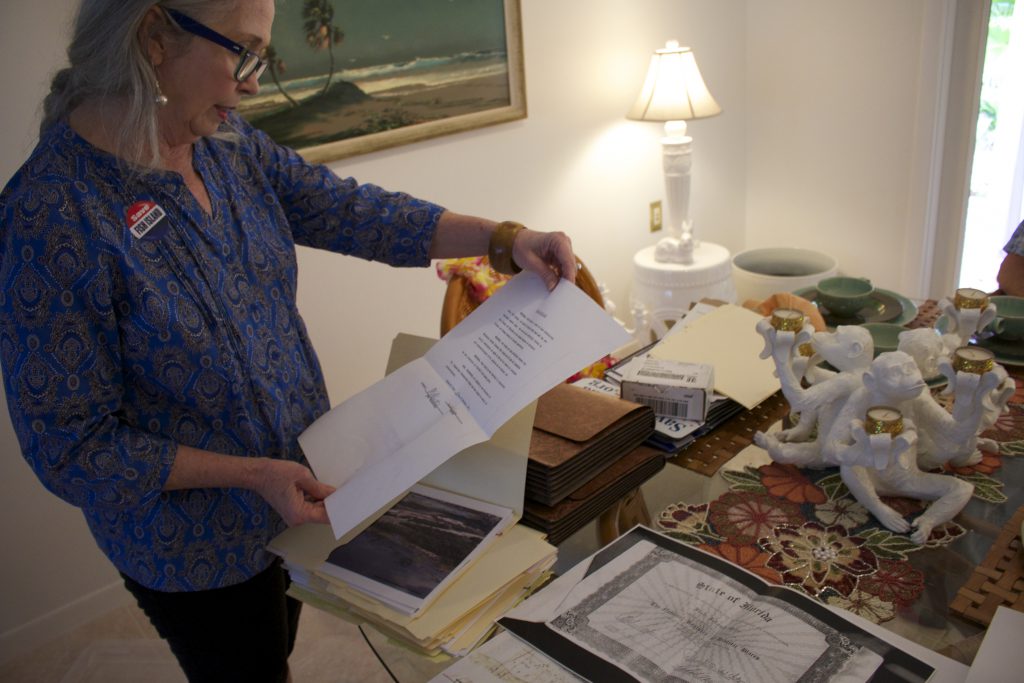

Susan Hill reviews a journal entry, one of her many documents on Fish Island’s history. / Photo: Max Chesnes

One online petition to save Fish Island has received over 3,500 signatures since its creation in July. While signatures are a great place to start, more action and advocacy need to take place, Hill said.

Hill’s drive to save the peninsula is inspired in part by what she sees on the south side of the 312 bridge as she drives toward the ocean from the mainland.

Like many St. Augustine residents, Hill commutes daily over the 312 bridge to get to US Highway 1. On one side of the bridge lies untouched Fish Island. The other is a warning sign for the island’s potential future.

Antigua, a future residential neighborhood by development group Dream Finders Homes, is under construction. All trees have been removed from the land.

“One day I looked to the right and saw this previously undeveloped land now looked like the face of the moon,” Hill said. “It was completely flattened.”

Lush Fish Island, with all of its trees and wetlands, stands in poignant juxtaposition to the construction project already underway, Hill said. It is a reminder for what could potentially happen to this land – and much more of St. Johns County and Florida.

“I was so horrified, I couldn’t believe it,” Hill said. “I’m so tired of seeing our natural resources disappear.”

PHOTO GALLERY: St. Augustine citizens spread awareness at the local farmers market.

Peak Florida

Peak Florida