BITTER TASTE

Nearly 20 years after citrus greening appeared in Florida, exhausted farmers and researchers struggle to survive a disease destroying the state’s quintessential crop.

By Abigail Hasebroock | May 8, 2023

On the outskirts of the University of Florida’s sprawling campus in Gainesville, fruit trees stand in rows on about 17 acres of land.

Before the university razed part of it to make room for the new baseball stadium to the north, the UF/IFAS Horticultural Sciences Research Grove was almost twice as big. During games, foul balls occasionally fly into the grove. At least 50 have been found.

Today, people who stream by each day on cars, buses and bikes may not even notice the remaining fruit orchard, wedged between the stadium and a scraggly forest.

But José Chaparro gives it almost all his time and attention.

The 64-year-old UF horticultural sciences professor has researched fruit breeding across the world, but he spends much of his time among the citrus trees, which include oranges, grapefruits and lemons. Chaparro is part of a statewide research army that has fought for nearly two decades against citrus greening, a disease ravaging a signature Florida industry. Spread by bugs, the disease has pillaged thousands of groves and forced many farmers out of business.

UF’s shrinking orchard is an emblem of the statewide groves its researchers are trying to save. Last year, Florida citrus inventory stood at 361,656 acres of orange and grapefruit trees statewide. That’s less than half the 1996 acreage, when more than 800,000 acres of sweet-smelling trees stretched across the state.

The farmers on those remaining acres are frustrated by the continued losses and lack of solutions to greening after pouring in millions toward research investments from their box taxes over the past 10 years. Millions more in Florida tax dollars have been directed by the legislature in an attempt to combat greening. Some farmers and others are now questioning both the research spending and the state’s outdated citrus policies.

This is the tale of the modern orange, the tiny bug killing it and the conflicts that have arisen in a once-dominant industry—now fighting for its life.

It’s not easy being green

Citrus greening, known scientifically as huanglongbing (HLB), originated in China and was detected in Miami in 2005. Ironically, the orange was named the state’s official fruit the same year.

By then, Florida’s citrus farmers had withstood freezing temperatures, hurricanes and citrus canker, another tough disease. But growers always replanted. Fourth and fifth-generation farmers would not exist otherwise. Yet, greening turned out to be the vilest enemy of them all.

Orange production is measured in 90-pound boxes. More than 40 million of them were filled in the 2021-2022 season. That’s a fraction—roughly 16%—of the 240 million boxes filled 20 years ago in 2003-2004, before greening settled across Florida.

The most recent USDA forecast for the 2022-23 season stands at 16.1 million boxes. The sharp decrease is due in large part to Hurricane Ian ripping through southwest Florida. The disease exacerbated the challenges farmers face in the wake of the Category 4 storm.

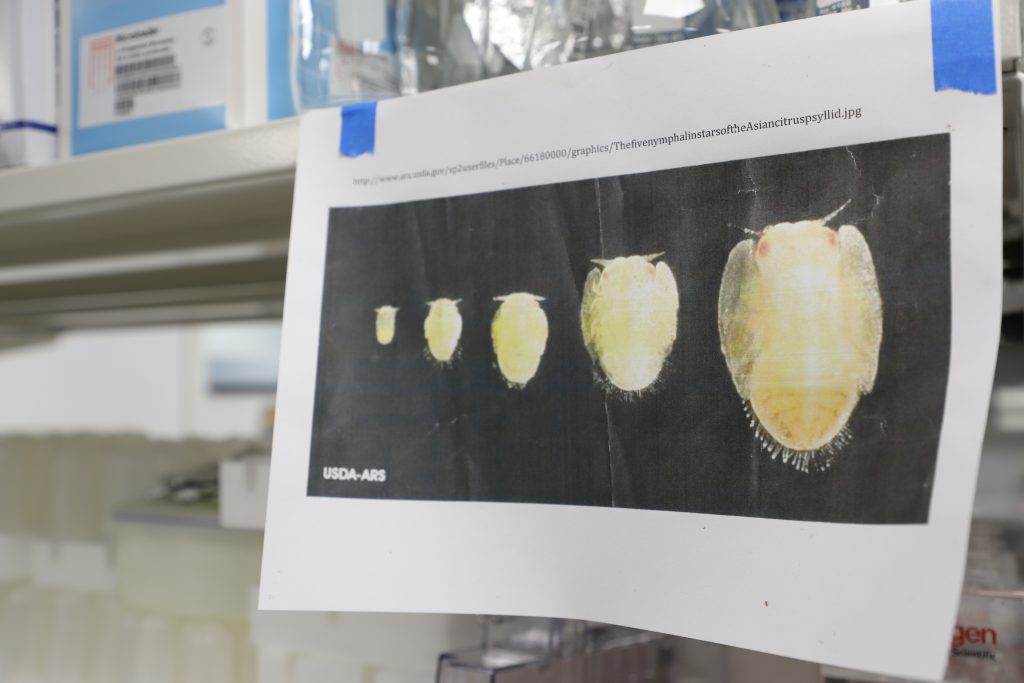

Greening spreads by a bug known as an Asian citrus psyllid. The brown bug only grows to be about 3 millimeters long, about the size of a flax seed or chili flake.

Like all living creatures, the villainous bugs need fuel, and they find it by feasting on citrus tree leaves. Their saliva carries a bacteria, which the bugs leave behind after meals. This bacteria chokes the flow of sugar and minerals in the phloem, which is the tissue that pulls water and nutrients from the roots and spreads them to the rest of the tree.

Researchers with IFAS—the University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences—use the analogy of blood through human veins and arteries. “The effects of citrus greening are comparable to what happens when the human vascular system is damaged and blood flow is restricted,” they explain.

The disease has been likened to plaque buildup and even death by starvation in how it infects a tree and strips it of its life-giving nutrients. The pests leave behind white stringy tubules, which would be beautiful draping over leaves and branches like celebratory streamers – if they didn’t signal abject devastation.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s 2022 Commercial Citrus Inventory reported 343,659 acres of orange trees statewide.

Ned Hancock believes the current acreage may be even less.

“I think those numbers are somewhat inflated, not intentionally, just because there’s no real good way to know,” he said

Hancock is a fifth-generation citrus grower in Highlands County and the former chairman of the Florida Citrus Commission. He said many growers feel forced to sell their land to developers because of how greening has decimated their groves.

“I think most of what got sold into development would not have, had it not been as difficult as it is now,” he said.

Before greening marched into Florida, Hancock managed 3,200 acres. Now, the acreage is less than half.

“It’s staggering to me what the overall acreage loss in this industry has been and how little really actually remains,” he said.

Fruitful or fruitless research?

Eradicating greening is the primary goal for institutions across the state of Florida. The number of citrus industry entities, agencies and committees — the Florida Department of Citrus, the Citrus Research and Education Center, the Citrus Research and Development Foundation, Florida Citrus Mutual and the Florida Citrus Commission, just to name some — is evidence of the bureaucratic effort.

“You’ve got every little group that's ever been put together focused on one thing because without an answer to greening, none of it matters, and none of them matter,” said Brantley Schirard, Jr., a citrus farmer in Fort Pierce. “You’ve got everybody pulling on the same end of the rope probably for the first time in the industry’s history.”

The disease is, so far, incurable. Despite their size, psyllids spread the disease quickly and far. The little bug may travel more than a mile in less than two weeks. Pesticides couldn’t keep up, and farmers often found that by spraying more, they were killing off both good and bad organisms while still not eliminating the bug.

The initial approach to greening was misguided by past industry failure. Citrus canker, an infection that spurs lesions on the stem, leaves and fruits of citrus trees and spurs premature fruit drop, was the largest threat to the citrus industry in the 1990s, so a canker eradication program was formed. But the program had devastating effects.

Florida law mandated cutting down citrus trees within 1,900 feet of a canker-infected plant, which resulted in the removal of thousands of otherwise healthy trees, including those on private properties, leading to a lawsuit.

The state has since shelled out millions of dollars to homeowners across the state, which is why Peter McClure, a fourth-generation citrus farmer, said no one had the stomach for a greening eradication program.

The state did not want to risk such a drastic economic disarray again. But even if officials had, the bug and greening are pernicious. McClure said one pathologist told him canker is like the common cold while greening is like liver cancer.

So researchers are now focusing on finding feasible ways to successfully live with the disease rather than defeat it. Some of the best examples are found at the Citrus Research and Education Center at Lake Alfred in Florida’s Polk County.

The citrus research center employs people from around the world, all actively and extensively researching ways to combat greening.

Laura Waldo, a biological scientist, works with Citrus Under Protective Screens (CUPS) technology, which is just as it sounds: Citrus trees grown in screened-in enclosures to fend off bugs. Kirsten Pelz-Stelinski, an entomology professor and CREC associate director, explores how to alter the bug. Tripti Vashisth, a citrus extension specialist and horticultural sciences professor, studies how gibberellic acid, a natural plant hormone, can stimulate growth for citrus trees amid greening.

Laura Waldo, a biological scientist, stands inside a screened-in enclosure that operates the Citrus Under Protective Screens at the Citrus Research and Education Center. (Abigail Hasebroock/WUFT News)

In the same CREC grove with the IPCs are trees with a pinkish-red coating called kaolin clay that is thought to discourage psyllids away from the plant. (Abigail Hasebroock/WUFT News)

Another approach used at the CREC to combat greening is individual protective covers (IPCs) that keep the bug away from the citrus trees. (Abigail Hasebroock/WUFT News).

Among the IPCs and the kaolin clay covered trees is a row where reflective mulch is used as another way to repel the bugs away from the trees. (Abigail Hasebroock/WUFT News)

Perseverance defines every research experiment and conversation. In November, CREC was awarded a grant of more than $16 million for citrus greening-related projects.

CREC Director Michael Rogers said as growers’ yields dwindle due to greening, funding from state and federal sources has stepped in to continue supporting research projects so that growers are no longer providing the primary source of money to the industry.

Still, some growers, like Ned Hancock, remain frustrated with the disease and particularly Florida’s efforts to fight it – regardless of the funding source.

“I see the amount of money we’ve dumped into this research, and how little we’ve actually gotten,” he said. “Some people tell you, ‘Oh no, we’re a lot further along than what you think.’ All I know is after 15 or 16 years, we’re still in a downward spiral.”

Fruitful or fruitless funding?

The Florida Department of Citrus taxes the 90-pound boxes of citrus that move through the Sunshine State’s processing plants and packinghouses.

These so-called box taxes are set each year by the Florida Citrus Commission, a 12-member board appointed by the governor that oversees the Department of Citrus. A tax is set for the fresh and processed fruit markets – the former for fresh fruit and the latter for juice.

For the past two decades, the combined tax has hovered from anywhere between about 12 cents to as high as more than 40 cents. For this season, the taxes are 5 cents for fresh oranges and 12 cents for those processed into juice.

Until greening muscled its way into the industry, most of the Florida Department of Citrus’ budget was devoted to marketing. The investment included everything from commercials to crate labels.

But once the disease permeated groves across the state, scientists sought to divert funds from marketing and into greening-related research.

Peter McClure was one of the champions of this change. He was part of a research advisory council that agreed there was not enough money funneled into greening research efforts in the early 2000s – even though the disease’s damage was well-known by then.

McClure said the council approached the Florida Department of Citrus with a proposal to move some of the marketing funds from the box tax budget to greening research.

“That was a hard sell,” McClure said. “It was a lot of the growers against that.”

McClure said many growers did not want to take away from Florida’s citrus marketing program, which had a long history of success. Greening was also not seen as severe of a threat as it actually was, he said.

“The argument I was making to the industry was, you’re not going to have anything to advertise if we don’t do this and don’t solve it,” he said.

The Florida Department of Citrus redirected some of the funds to disease research, starting with almost $2 million in the 2007-2008 season’s budget and then to more than $7 million in the 2008-2009 season.

The department’s annual financial reports from 2007 to 2015 indicate $45,397,269 was spent on disease research.

The research advisory council that McClure served on eventually turned into what is now the Citrus Research and Development Foundation – an organization that distributes money to research projects across the state – including other UF/IFAS centers.

Even now that most of the funding comes from state and national levels rather than from growers’ pockets, hesitation to invest in new research lingers.

Former Citrus Research and Education Center director Harold Browning said because citrus trees have a lifespan of about 50 years, growers are cautious about jumping into new varieties of fruits or new ways to manage crops. So even if research produces a promising method, many growers may tread carefully for fear of losing already fragile crops.

“A mistake in planting the wrong variety, for example, may cause you to live with it for decades,” Browning said.

In 2009, UF released its first new citrus variety: the Sugar Belle, a highly HLB-tolerant mix of a mandarin and an orange.

Still, farmers fear the risk involved.

“A lot of people have lost their resolve in the way they’ve lost their growth, and they’ve lost their livelihood,” Browning said. “And so it’s difficult now to consider implementing a whole new range of strategies when you’re just struggling to survive.”

Public communications also had a hand in generating what was fruitless buzz, Browning said.

“The PR that surrounds science is always looking for a breakthrough,” he said. “The public relations department at the University of Florida would put out press releases that we’ve discovered something, we’re really excited about it, it looks like something nobody’s done before, we think it’s going to have great impact, and so on.”

Recent releases include: “UF/IFAS Scientist to Work with Team Developing New Greening-Tolerant Citrus” published on Feb. 11, 2019; “Florida’s citrus growers have new tool to help fight citrus greening” published on July 21, 2020, and “University of Florida researchers discover new way to potentially control citrus greening” published on March 16, 2021.

Those releases put UF in the spotlight, Browning said, but also created unrealistic expectations.

“People tend to get excited because you want it so bad,” he said. “The scientist wants to make the breakthrough, they want to get the material out, they want to be recognized as part of the solution.”

Michael Rogers, CREC director, said the dissemination of that information is a way to remain transparent about the center’s work and progress, a request growers made to researchers, he said.

“We learned so much that we’re able to then continue to direct new research projects on areas that did make sense, that showed promise,” Rogers said. “We’ve been able to keep the industry going as we’ve learned bits and pieces over time and put this story together.”

Ultimately, the enemy was and always has been the disease, eviscerating crops, time, money and hope.

“No one really said ‘Hey, we wasted all this money,’ although I’m sure people think that,” McClure said. “In hindsight it’s absolutely true.”

Overripe rules and regulations

The USDA says American orange juice must contain 90% juice from sweet oranges – also known as the Citrus sinensis variety.

“It’s analogous to picking a person at random from the population and using that person as the definition of human,” José Chaparro said.

Even if a fruit breeder – Chaparro, for example – develops an orange variety that’s tolerant to greening and produces sweet-tasting, brightly colored juice, it cannot be used unless certified by the Florida Department of Citrus.

“No other fruit industry is limited by law to such a narrow genetic base,” wrote researchers in a journal article. “Apple juice can include juice from any combination of the 7,500 recognized apple cultivars.”

Cultivar is another term for plant variety.

They also wrote: “The current U.S. regulation defining orange juice as being almost exclusively from C. sinensis locks the industry into a very narrow range of genetic diversity, leaving the Florida citrus industry extraordinarily vulnerable to epidemics when diseases or pests emerge to which sweet orange is highly susceptible, such as HLB.”

The Gainesville research hub houses a breeding program where Chaparro and other scientists, some who are students, breed oranges with the hope of producing a cultivar tolerant to greening. They might take the rootstock from one plant, like a lemon tree, and graft it with a portion of another tree type.

“We’re matchmakers,” Chaparro said.

Some grapefruit varieties there are hulking spheres with nearly translucent inner flesh. Other fruits, like some of the orange varieties, are tiny but explode with overwhelming sweetness.

Others are deceptive to the eye – their scintillating exteriors do not match the highly acidic or even bitter flavors hidden inside. Conversely, some oranges’ outsides are spotty, green or both, making them poor candidates for first picks at grocery stores. Yet their pulp radiates a colorful, eye-catching brilliance.

Some are easy to peel. Some are not. Some ooze juice and leave behind a stickiness that gloms for the rest of the day. Others are dry, almost oily.

“These very strict characteristics make the job of the breeder much more difficult,” Chaparro said. “We’ve come close to looking and tasting like a sweet orange, but we’re not there yet.”

Chaparro’s varieties face another hurdle: Brix.

Named after scientist Adolf Brix, it is a measure of dissolved sugar content in soluble liquids, including fruits. The USDA requires pasteurized orange juice, the kind you might pick out at a grocery store, to have a Brix level of at least 10.5.

That figure is arbitrary, said John Barben, a grower in Highlands County with his brothers, Bill and Bobby.

“That’s something that the growers put on themselves years and years ago to protect themselves, but we also want to protect the consumer with good taste and juice,” Barben said of the three-decades-old regulations. “What’s happened with greening is our sugar levels have come down in a box of fruit – it’s hard to meet those standards.”

The Barben’s farm has endured for more than a century. Their grandfather, Earl Hartt, served on the state’s first citrus commission.

“I am hopeful that under the leadership of the commission, the industry will unite in a program to improve and standardize our cultural packing and handling practices, so that Florida fruit will be of better and more uniform quality,” Hartt wrote in a journal article in 1936.

The Better Fruit Program was created in an effort to grow and produce the highest quality citrus harvest possible, with strict standards for everything from color, sweetness and size.

But greening makes growing citrus harder now than in the 1930s. And though Earl Hartt set the precedent for standards like the minimum Brix level, Barben thinks it should be quashed.

“It is no longer applicable in this day and age,” he said.

Florida lawmakers agree. Last summer, U.S. Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Florida) sponsored bill S.4394, the “Defending Domestic Orange Juice Production Act,” in an effort to lower the Brix level requirement to from 10.5 to 10.

Growers, breeders and politicians agree: The consumer would not detect a difference.

“What we’re saying is,” Barben said, “Hey, we’ve got a commodity that the standards are too high in this day and age, with the pests and disease, so let’s lower it, so the U.S. product, what we’re producing, can go into the juice container.”

Rubio’s bill stalled last year, but he and U.S. Sen. Rick Scott (R-Florida) reintroduced the bill this year as S.103 - “Defending Domestic Orange Juice Production Act of 2023.”

In the House of Representatives, U.S. Rep. Scott Franklin (R-Florida) and U.S. Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz (D-Florida) introduced an identical bill in March. The bill has 20 cosponsors, both democrats and republicans. It was last referred to the House Committee on Energy and Commerce but has made no progress since.

Developing an orange variety that is greening-tolerant, has at least 10.5 Brix, is peelable, is not too juicy and has a beautiful orange color would be ideal. But time is not on anyone’s side, and neither are the current regulations, which were created to ensure consistent quality.

“It’s a difficult endeavor,” Chaparro said. “It’s not impossible, but difficult.”

Peeling a way forward

In 2005, David Schifino bought a 20-acre plot of land in Odessa, just north of Tampa, to grow orange trees and raise animals.

The 56-year-old enjoys growing and raising plants and animals, and his fruit would often end up at mom-and-pop shops and fruit stands in the area.

Researchers from UF/IFAS inspected his trees to analyze the effects of greening in a small grove, he said. Producing profitable fruit was an uphill battle, so Schifino said he burned all the trees in 2010 and converted the land to pasture. Two years later, he sold 75%, or about 15 acres.

He hopes to one day own an orange tree orchard that people can visit.

“That’s what I wanted to do with this 20 acres,” he said. “Obviously it wasn’t in the cards…it’s not even on my radar because they don’t have a cure.”

Schifino said he received an email from someone encouraging him to try growing bamboo. He probably won’t bite. But he remains optimistic, and so do other growers and researchers in the state.

“Hell, I’ve got enough property now I could plant 50 trees,” he said. “Would I love to do that? Absolutely. I’d love to plant 50 trees, set them up again, and do it in such a way that was more of a venue, a private venue that is beautiful. You could come with your little kids and go pick some oranges and go into a bunkhouse somewhere and squeeze them and kind of do the whole thing. That’s what I want to do.”

For commercial operations, one method showing promise is called oxytetracycline injection. Oxytetracycline is an antibiotic used to kill bacteria – in this case, the bacteria left behind by the psyllids, the bugs that cause greening.

Oxytetracycline isn’t new. In the past, growers tried spraying it onto the crops to ward off the bacteria, but that method wasn’t effective. Now, farmers are injecting the antibiotic directly into the tree’s rootstock.

In recent months, the Environmental Protection Agency has approved products that growers can buy and use to inject the antibiotic into their trees.

Another avenue is genetic engineering. This differs from genetic breeding – what Chaparro does – but has been proposed as a way to combat the disease because of the idea that a genetically modified greening-tolerant orange could be created and used on the commercial level.

But genetic engineering continues to generate debate. That’s why researchers at places like the Citrus Research and Education Center and Gainesville’s research grove employ methods like genetic breeding and gene editing, which is nontransgenic. This means the fruit is not altered by the introduction of a gene from another species as is the case with genetically engineered organisms.

The losses and pitfalls of the past two decades have not shattered all hope. Researchers, farmers, breeders and even politicians alike remain vigilant. That’s why Chaparro often spends up to seven days a week working in his groves.

He spends long days under the scorching sun. His arms are riddled with thin scars from citrus tree thorns, a symbol of the war he and others in the industry are waging against the disease.

“Hopefully we will find either a cure for a disease or develop new varieties that are resistant,” he said. “There’s multiple breeding efforts, there’s multiple lines of investigation, in terms of treatments to help either the tree survive or keep the trees producing quality fruit. Many things have been tried.”

Chaparro sees a future where a new variety is developed. But with how low the current season’s forecast is, and with how long it takes for citrus trees to fully mature, the industry is as fragile as its weakest trees.

“It feels like we’re working off borrowed time,” he said. “We’re in crisis mode.”

Special Report from WUFT News

Special Report from WUFT News