By Tobie Nell Perkins | June 19, 2019

A young teacher struggles to save a failing Ocala school from shutting down

On the first day of March at Oakcrest Elementary School, teacher Haddie Peebles’s computer screen lights up in green, yellow and red. Lots of red.

At first glance, the reading results show immense improvement. Some of Peebles’ students have jumped an entire grade level; some have even jumped two. But no matter how she looks at the numbers, the truth is devastating. As it often does, the reality of working with disadvantaged children slaps her in the face. Only three are where they need to be: on fourth-grade level.

And that’s how the state will size up the Ocala school, which means that Oakcrest could have failing grades for the sixth consecutive year. Its future hangs in the balance.

But Peebles doesn’t let her disappointment show. She never does. Like always, she steels herself and moves forward, closing the window and starting the day’s lesson plan.

She can’t give up on her students now.

Today’s reading passage is about Hercules and his ten labors. As Hercules meets Atlas, Peebles has the students follow with her finger as one reads out loud. “Will you hold the earth and sky just long enough for me to get comfortable?” They look at her, waiting for their next direction. Will she?

Today’s reading passage is about Hercules and his 10 labors. As Hercules meets Atlas, Peebles has the students follow with her finger as one of them reads out loud. “Will you hold the earth and sky just long enough for me to get comfortable?” They look at Peebles, waiting for their next direction. Will she?

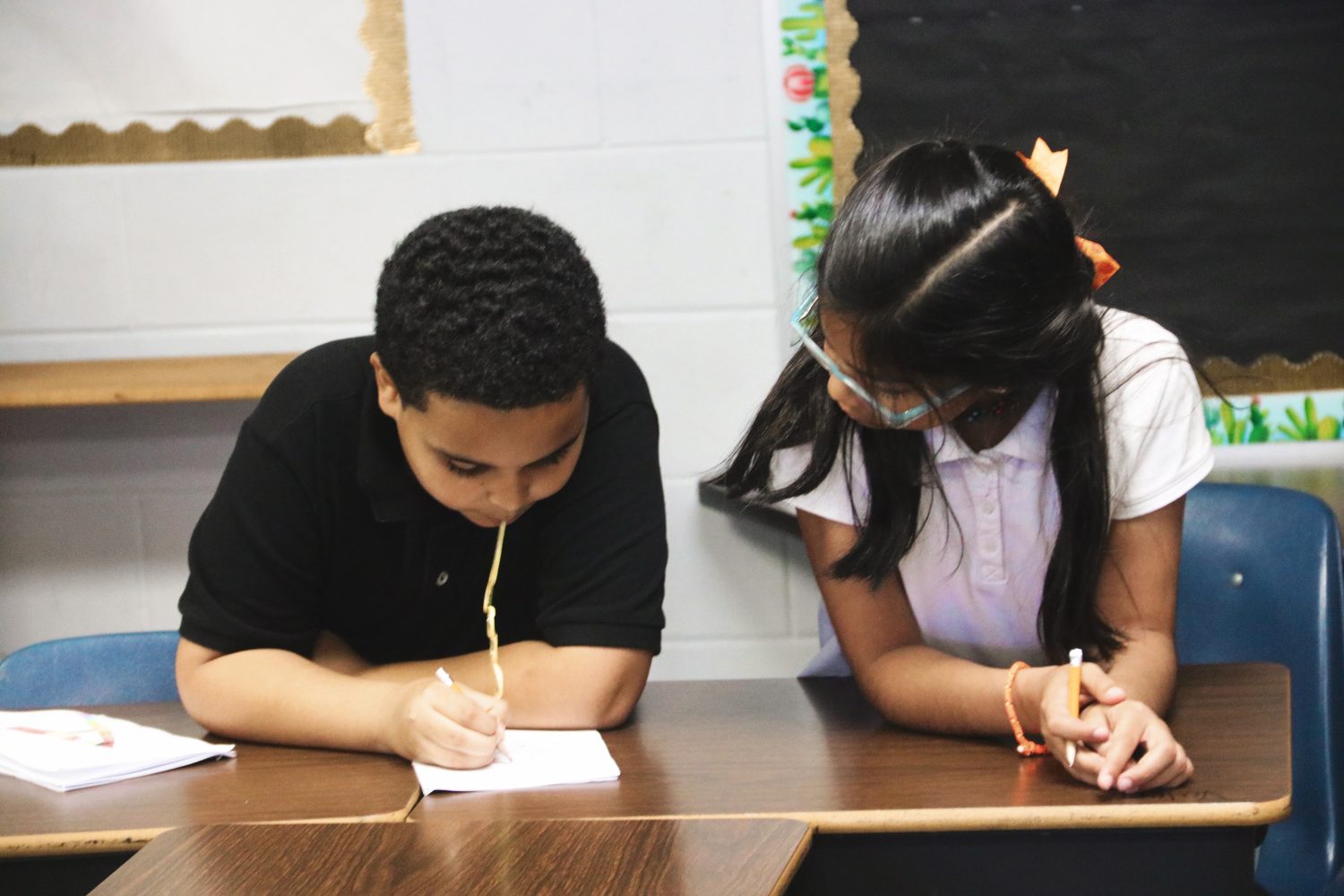

Peebles has worked tirelessly with her students all year, meeting them where they’re at. Some fly through their assignments; some can barely spell “fourth grade.” One never even lifts her pencil.

Most Oakcrest students entered kindergarten with no reading experience and a majority do not begin reading until second grade. They don’t know the alphabet; they have never picked up a crayon or pencil, even though the national Common Core standards call for kindergarteners to be able to identify words and read basic text. Some kids can even read books like Dr. Seuss’ “Cat in the Hat.” But that’s a dream at Oakcrest. Many students weren’t read to at home; they struggle to connect spoken words to written ones.

Peebles tries her best to close the gap; they work in small groups so each student gets attention, and she encourages them to ask about words they don’t understand. Misery. Arch. Quest. They grow their vocabularies every day as they tinker at essay questions that aim to prepare them for testing.

Peebles teaches her kids about mechanics and helps them with spelling. She supervises while they work at online reading programs like iReady, which adapts to their reading ability. She knows where each one began and what they need.

But time is running out. Peebles and the other 90 teachers and staff at Oakcrest are trying desperately to save their school. Since 2014, the school has consistently earned a grade of D, and it has now been named a “turnaround school.” If the 2019 scores show no improvement, the state of Florida will intervene.

Oakcrest could be turned into a charter school, taken over by an outside operator, or, worse, close completely. All three options bode ill for Peebles.

And even more so for her students. There is no school bus to Oakcrest – all the students live within walking or driving distance. If Oakcrest were to close or become more exclusive, their futures stand to become a lot murkier.

The spring semester seems as short as it is long.

There’s not enough time for Peebles to get her students on par; so much time to worry. The stress is hard to shake, even for someone as perky as Peebles. She often gets stomach aches and headaches. Her fuse with the students has grown shorter. She’s tired.

Peebles knows she has a Herculean task at hand. Last year, only 14 of the school’s 2012 fourth graders passed the language arts exam. Among her approximately 40 students, 14 must earn a proficient score on the reading test to help Oakcrest reach a C. With Spring Break on the horizon, she has only three weeks to get her job done. No one wants to fail again.

Employees at Oakcrest like to say each student has two selves: one who is ready to learn and one who comes to school after something goes wrong at home. It’s hard to predict which one will show up each day.

It’s an even bigger challenge because the kids at Oakcrest come from poor homes; 100% are classified as economically disadvantaged. Some cope with broken and abusive families. Many show it on their faces. Many act out in class. Oakcrest staffers like to say each student has two selves: one who is ready to learn and one who comes to school after something goes wrong at home. It’s hard to predict which one will show up each day.

Peebles, 29, is in her fourth year teaching at Oakcrest. That makes her a veteran. Most don’t last that long.

She grew up in Gainesville, just 40 miles down the road. Teaching ran in her veins. She followed in the footsteps of her mother and grandmother. After earning a bachelor’s degree in education, she moved to Marion County, where teachers are paid more than in neighboring Alachua. At Oakcrest, she found herself in unfamiliar territory; she had little experience with troubled children.

She stands 5’3 and with her brown bob and bright blouses, she seems an unlikely candidate to weather the storm that is Oakcrest. But for her students, she is relief. She is the calm in the eye of the hurricane.

And without a doubt, she has made a difference. As has Diane Leinenbach, Peebles’ boss.

Leinenbach took over as principal in 2017 and immediately noticed many of the parents were simply not engaging. About 14% of the 343,353 people who live in Marion County are classified as illiterate. Nearly 20% of all households earn less than 15,000 a year. Many parents work more than one job and the stresses of life leave little room to focus on their children’s education. While some assign extra work at home, trying to help their child catch up, some just don’t know where to start.

The parents see Oakcrest as a home, a place where their children are seen, heard and helped. They can’t see their children going anywhere else, and many panicked when their children were assigned to other schools for the fall. But few of them are informed about the battle the school is fighting.

Whatever the reasons, Leinenbach wasted no time in getting to the root of the problem. Students who don’t know how to behave, she believes, struggle to learn. In the past, when teachers challenged their students, they would lash out. Teachers were reluctant to challenge them, and there was no push to fill the gap in their reading skills.

The past two years at Oakcrest, students have learned coping skills. When they feel sad or frustrated, they’ve learned words like “stressed,” “anxious,” and “depressed” to understand their feelings. They’ve learned to step away for a minute, breathe and come back to the situation.

Students who have started their tenure at Oakcrest under Leinenbach are being prepared to close the gap early on. And they are starting to catch up.

At 7:30, as she does every morning, Peebles greets each one of her students on the way into the classroom.

Some try to get past her unnoticed, but she stops every last one to hug them.

The children begin settling down. Some are in the midst of a game. Rick has been “paused” by one of his classmates, and he looks around anxiously.

“Unpause me, the teacher’s right here!”

Peebles shakes her head as she passes by.

“That’s right. The teacher’s right here,” she reminds them, part scolding and part loving. Rick sits in his seat, back straight, standing attention. Peebles tries to project urgency.

“It’s March!” she announces. She might as well be screaming, “Fire!”

Peebles projects urgency. And why not? In a month, her students will have to write complete essays for the Florida Standards Assessments. On this day, they are still reviewing basic capitalization. A couple of them are still struggling to put spaces between words.

The kids begin their first assignment, and Harmony is already lagging behind. She’s 10, tall and showing off her lanky legs in shorts, even though winter’s chill is still in the air. She sits perfectly still; never even puts hand to pencil.

Peebles has been playing close attention to Harmony for a few weeks, worrying over the empty look in her eyes. She won’t tell Peebles what’s wrong. Peebles wishes she could bring her home, away from whatever is troubling her. She wishes that for a lot of her students.

Peebles kneels beside Harmony’s desk, asking her gently to pick up her pencil.

“Is there any issue today?” she asks. “This isn’t normal Harmony behavior.”

Harmony doesn’t answer. She just picks up her pencil and starts to read.

Tamia, a new student, refuses to complete her work. She’s a quiet girl with pink beads in her hair; she lets them hang in her face like a curtain between her and her classmates. She has only been on task one time since joining the fourth grade. Peebles approaches her with the same patience that has gotten her through the last four years. She’s made up a special chart for Tamia and if she doesn’t need to be redirected and completes the chart, she can receive a reward up to three times a day. To Peebles, students aren’t a lost cause. If they’re not catching on, she starts getting creative.

Others forget to cite a source, something Peebles has warned them will earn them a “big fat zero.” A small voice calling “help!” stops her in her tracks; a student has dust in their eye, and Peebles helps them calmly get it out. Rick, who started the year at a second-grade reading level, gets in trouble for running around backwards. Every student stumbles at one point or another.

Peebles is there for them all.

Each day at Oakcrest is like an obstacle course.

A few weeks ago, it was lice. Three girls came to school with the bugs clamped onto their heads. On the walk back from lunch, the rest had to be checked. They lined up to see the nurse, each fraught with fear when it was time to face the inspection.

Then, an intruder entered the already tense atmosphere: a bee. Peebles warned the kids to stay still, but shrieks carried through the line. Some made a break for it.

“Even when we’re hyperactive, we can have self-control, right?” Peebles told them. One of her many mantras. She knows the students are smart enough to figure things out for themselves. They mulled it over, and slowly began to nod. Right.

The commute to the classroom was a fair picture of life at Oakcrest. Hurdle after hurdle, and this was just the walk from lunch. And always, among the chaos, there is Peebles.

She grounds them for as long is humanly possible.

When they finally shuffled into the classroom, lice-free, the students set to work on a sentence projected on the board. They sat in little desks arranged into groups, surrounded by walls mosaicked with old activities, charts denoting achievements and pictures they’ve drawn for Ms. Peebles.

All settled down except one, a tiny boy outfitted in a blue polo and khaki pants. As the other students argued with Peebles over the capitalization of “Nevada,” (“Is it a town?” “Is it a country?”) he laid his head down, chewing on his pencil.

Outside the nurse’s office, he was flashing a toothy smile and joking around. Lice didn’t scare him. He retreated inside himself, eyes anywhere but on the board. Peebles asked him to go and sit by himself, but he ended up cross-legged on the carpet, quietly flipping through a textbook he found and fixing its dog-eared pages. This is the alter-ego Leinenbach describes; a child who turns up for school with much heavier things on his mind.

She tries to cut her kids some slack, but she believes that one child’s rights end where another’s begin.

But the one thing she doesn’t tolerate is students distracting others. She can’t afford to let that slide. The sand is trickling out of the hourglass.

She told the class they wouldn’t be able to do a fun pairs activity because some “friends” weren’t behaving. The student mumbled that he was sorry, but stayed rooted to the carpet.

Peebles knew the boy was having problems at home; he’d announced to his morning class that when he’s in trouble, his stepfather doesn’t let him eat.

Situations like these are not out of the ordinary. She’s had students who saw their father get shot; another said her parents were arrested. She notifies the appropriate state authorities and knows she might have to call again. But then she keeps going. There is no choice.

In this case, Peebles sent her disruptive pupil to the dean’s office and continued with class. The tests would come as sure as Florida would heat up in the spring.

Each day, two hours after the final bell clangs at 2:30, Peebles packs her things and leaves Oakcrest to make the short drive home. She shares a house painted shades of pale blue in an Ocala subdivision with her fiancé Tim and her stepdaughter Evie. They planted infant fruit trees in the yard: orange, lemon and a peach. She and Tim will be married in June, shortly after the fate of Oakcrest is announced, and she takes solace in this place of love.

But Oakcrest never really leaves her.

One afternoon, Peebles plants herself in the rocking chair on her front porch while Evie, finishes her homework. Evie is 7 years old and is finishing second grade. Oakcrest is only 8 minutes away, but Evie attends Dr. N.H. Jones Elementary School, the “A” school about five miles from their house. Peebles couldn’t imagine Evie at Oakcrest. It would slow her down, hold her back.

With a little bit of help, Evie flies through her math assignment and then saunters over to ask for homemade lemonade. Peebles’ own students would never be able to keep up. It’s but one of the many reminders of the daily hurdles she faces at school.

One recent weekend, when she, Tim and Evie went shopping at Best Buy, they came across two young boys panhandling outside. Tim pointed out that when the boys saw them, they tried to hide – as though they recognized Peebles. And they did. They had been her students.

The incident haunted Peebles for days. How long had they been out there? Where were their parents? She understood her students’ life situations were not easy. Still, she found it frustrating sometimes to play teacher and parent all at once in the classroom.

On some days, she comes homes and watches the dogs run. On other days, she cries. Or sips a cold beer.

Yes, life at Oakcrest is a struggle. Or it’s just plain human.

She knows her kids are no different than the kids who go to Evie’s school. And they love her.

One day in class, many of them panicked when she mentioned she was feeling lightheaded. They jumped up from their desks, all babbling “are you okay?” at once.

They bring her little gifts throughout the year; cozies and bag clips and sets of markers. And they are crushed when they can tell they have disappointed her.

With help from teachers like Peebles, many of them are becoming leaders. One even listed the names of classmates who are bullies. They want to succeed; when report cards are distributed, they trade them and celebrate the As and Bs. Former students rush up to Peebles after school, waving their report cards.

They know if they are good, they can have the class pet, Izzy the hamster, roll around on her exercise ball while they study. That’s Peebles’ way of lightening it up in class. Yes, the tests are coming. But they’re just 10-year-olds, after all.

On the Friday before testing begins, Peebles rips down and covers up all of her carefully hung posters. Any educational material must be off the walls by the following Tuesday. Then, she picks up a yardstick and carefully measures three feet between each desk.

Once the tests are distributed, Peebles will not be allowed to assist in any way, except to say: Try your best.

She is hoping her kids might be able to do well enough to hit the target scores. Just barely. They’ve got to. The future of Oakcrest rests with them.

The staff agrees the scores will be close. In 2017, no second graders at Oakcrest could read. This year, all but eight can. And every kindergartner is on grade level, with only one percent falling behind. The students are no longer operating on a deficit. Maybe when they get to fourth grade, when they face Peebles, they’ll be ready to write essays.

A score of C is all the school needs. But Leinenbach isn’t sure. No one is. Nor can they be.

The school year will soon end and the summer break is sure to bring well-earned relief for Peebles. But it will also bring uncertainty. Scores will be finalized on June 20 and Oakcrest could be a very different place come fall.

The school year will soon end and the summer break is sure to bring well-earned relief for Peebles. But it will also bring uncertainty. Scores will be finalized on June 20 and Oakcrest could be a very different place come fall.

No matter what the scores, Peebles is ready to embrace them. These are her kids, after all.

On the big day, Peebles pulls out a large piece of chart paper. On it she writes: “You’re braver than you believe, stronger than you seem and smarter than you think.”

She signs it, “Ms. Peebles,” and hangs it in the front of the classroom.

Editor’s note: WUFT reporter Tobie Perkins began visiting Oakcrest Elementary School in late February and reported this story until mid-June. She spent considerable time observing Haddie Peebles’s fourth-grade class and interviewed Peebles extensively. Perkins spoke with Oakcrest Principal Diane Lienenbach, who shared school data. Perkins also interviewed students, other teachers at the school and the school board representative. She examined pertinent documents from the Florida Department of Education. She contacted several parents but they were either reluctant to be interviewed or did not return calls from Perkins.

Special Report from WUFT News

Special Report from WUFT News