Bahamians struggle to start over

in the weeks after Dorian’s devastation

Video story by Mackenzie Behm

Tanya Fox ignored evacuation warnings three years ago when Hurricane Matthew pummeled the Bahamas with its Category 4 fury – and survived in a nearby hotel. So when Dorian threatened, she again decided to ride out the monster storm.

She was convinced she would remain safe, she said. “Until I saw that it turned into a (Category) 5.”

Or “Category Hell,” as the United Nations chief later described it.

Fox had never called anywhere but Grand Bahama home and she certainly didn’t want to abandon it, even as the storm raged north across the Atlantic. She stacked sandbags around her door and again, fled to a nearby hotel.

This time, she would not be so lucky.

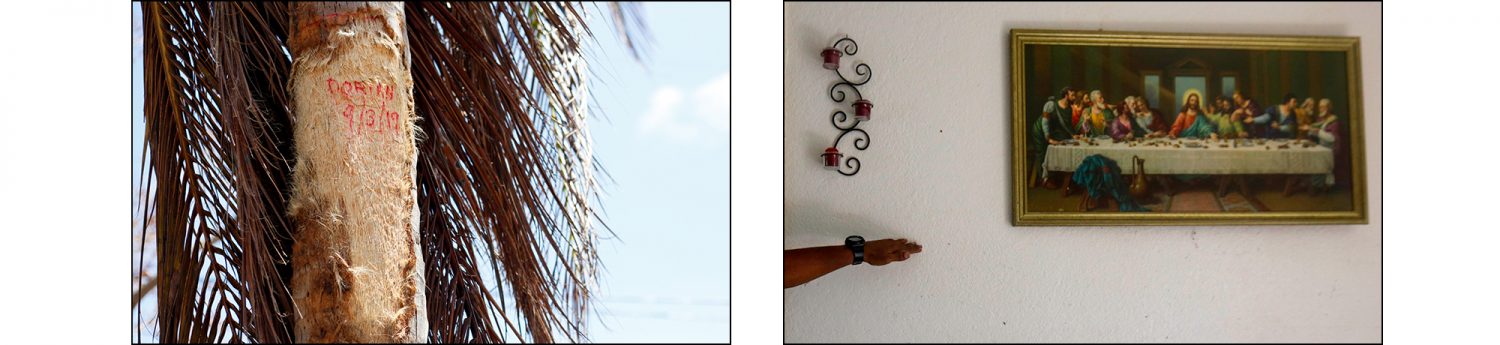

Dorian mustered massive strength over warm waters and lashed the Bahamas for almost 40 hours. It struck the Abaco Islands on September 1, slowly churned west to hit Grand Bahama and then stalled for a day, compounding the misery. The winds howled and gusted at 220 miles an hour. The ocean that was integral to life here roared ashore and swelled 20 feet high. Friend had turned foe.

Whatever hope Fox had harbored turned to utter fear.

Dorian left a calamitous trail of destruction in the Bahamas; at ground zero lay the Abaco Islands and Grand Bahama. In the days that followed, both officials and aid workers called the devastation systematic and unique in its vastness.

The government has reported 56 deaths, though it’s widely believed the toll may be significantly higher. More than 600 people are still listed as missing. The stench of death still taints the air in “The Mud,” an Abaco shantytown that once housed Haitian migrants, many of them undocumented. Visitors are told to wear face masks before approaching the community, but they do little to shield the odor of rotting flesh, a constant reminder of the catastrophe that befell the island.

Some risk modeling estimates put the Bahamas’ overall hurricane losses at over $7 billion. More than 13,000 homes were destroyed. The Bahamian government said this week that Abaco and Grand Bahama, alone, had lost $60 million in crops and marine resources.

Two weeks after Dorian, Lana Johnson, a nursing informatics specialist from Gainesville, Florida, carried pallets of aid to her homeland. She also served as a guide for University of Florida journalism students who spent a week in the Bahamas reporting this and other stories for the Fresh Take Florida news service.

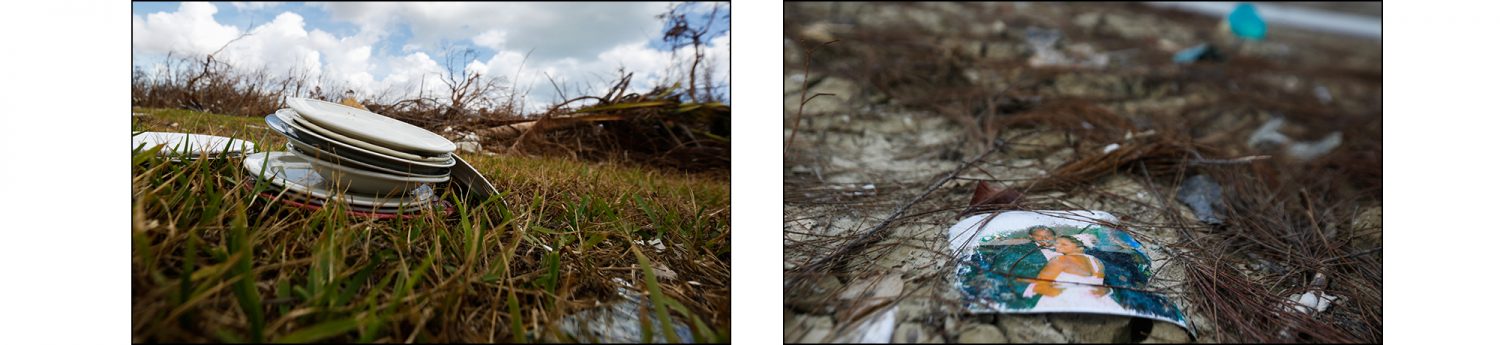

The Bahamas Johnson knew, the one that attracted thousands of tourists every year, was gone. Her heart broke when she spotted her compatriots picking through the rubble, desperate to salvage their possessions.

“Everything around us had lost its color, its luster,” Johnson said. “It was gone. Everything was just brown and destroyed.”

The long-term impact of Hurricane Dorian remains uncertain. But the 70,000 or so people who called Abaco and Grand Bahama home, including Fox, know one thing: it will take a long time to get back to normal. Or rather, a new normal. Dorian took with it everything that is basic to life: hospitals, schools, roads, gas stations, grocery stores.

In Freeport, the main city on Grand Bahama, the lines at relief kitchens wrap around the street corner and shelves in the water aisles of supermarkets remain bare. Many residents are still without power and water. A few lucky ones rely on their generators. People attempt to find fuel and food before sundown. The wait for gas is frustratingly long and the drive-through lanes at fast food places, like KFC, spill out onto the streets and clog traffic.

Some public schools – even in areas that weren’t badly flooded or escaped major wind damage remain closed – partly because of a lack of safe drinking water for young students. Other schools awaited the slow process of assessments by engineers that buildings wouldn’t collapse once classes filled with returning children.

Now, almost a month after Dorian, Bahamians are left to assess the loss and devise a plan to recovery. They are unsure how they will forge ahead when many are still reeling from the effects of Hurricane Matthew in 2016.

American Red Cross spokeswoman Jenelle Eli said the timeline for the Bahamas’ recovery is unpredictable.

“Losing your neighborhood, source of income, school, and sense of security all at once is heartbreaking,” said Eli, who was the first International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent team member to arrive in Abaco after the storm.

“Recovery from Hurricane Dorian won’t be just about clearing rubble and rebuilding—it will be about addressing people’s needs and meeting them where they are, so they can determine their own recovery alongside the government.”

Fox is trying to do just that. She returned home once Dorian’s fury dissipated, even though she wasn’t prepared for what she saw. How could anyone be?

“My home was just destroyed,” she said, wiping tears from her eyes.

Some Bahamians described Dorian’s destruction as “the devil’s work.” It was like nothing they had seen before.

Dorian left Fox’s refrigerator face down in the living room. Her bedroom furniture was scattered about the house. The carpet was peeled clean off the floors and kitchen tiles picked off as though they had never been set with cement.

She has begun the long and arduous task of removing debris and cleaning her house. But, she expects it will take months before she can fully assess her losses.

The United States has pledged nearly $26 million in assistance so far. USAID International organizations have executed a massive aid operation, but the sprawling island geography of the Bahamas and the extensive damage to infrastructure presented challenges in distribution of food and supplies.

Mercy Corps has pledged to deliver 3,000 emergency shelter kits to families. They also installed a tap stand at the YMCA that has the capacity to generate 7,500 gallons of drinkable water every day. Saltwater from the storm contaminated the more than 200 wells that Grand Bahamians depend on for water.

There are only two places on the island where residents can access clean water that’s not from a bottle, said Christy Delafield, director of communications for Mercy Corps.

“The estimates that we’ve heard about how long it’ll take for the water table to flush out the saltwater have really varied,” she said. “But for the foreseeable future you will be drinking saltwater.”[GWG4]

Samaritan’s Purse donated 130,000 liters of water to both Abaco and Grand Bahama islands and distributed over 280 metric tons of non-food supplies, including an emergency field hospital, which has already seen over 2,000 patients.

The Bahamas Red Cross has also been providing mental health support for evacuees and trauma victims.

On Abaco, residents are still dependent on goods brought in by the military and aid groups. Traz Nixon said survivors are getting desperate. Some people, he said, have been robbed at gunpoint over cases of water.

“It’s horrible because you could go on any social media site, you can watch any news media and you see warehouses filled with all kinds of supplies,” Nixon said. “But here – ground zero, the most affected – basically, you see nothing.”

Throughout Freeport, mud lines on walls are 8-10 feet high, marking where flood waters once reached. Dorian ripped off drywall, baring houses to wall studs. Entire neighborhoods look like landfills, reduced to giant piles of belongings. Appliances, dinner plates, wedding photographs, clothes[GWG5].

Residents have taken to burning debris in some areas, as they pick up the mess Dorian left behind.

In hard-hit Abaco, Dorian deposited cars and boats onto people’s yards. Shipping containers weighing 2 tons flew like missiles from the port miles away to land on lawns.

B.J. Swain stayed in his home in Abaco with his girlfriend during the storm until the flooding was waist-high. Unable to drive his car in the rising water, the couple hid with 30 others in a school bus parked nearby. The overall experience has been “absolutely terrifying,” said Swain, whose uncle perished in the storm.

“It was really scary,” he said. “The children on the bus were crying, screaming. Debris was hitting the bus. It was a lot.”

Swain returned last week for the first time to a house with no roof and half broken walls.

“There’s nothing to come home to now,” he sighed. “There’s nothing left. We managed to grab a few clothes that we can wash, but that’s about it.”

Swain, a draftsman by trade, knows the challenges that lie ahead in rebuilding so many homes and businesses. He plans not only to rebuild his own home, but he’s determined to help put his community back together.

Many of Swain’s family members encouraged him to relocate to Nassau, which escaped the wrath of Dorian. But the costs of moving and finding a place to rent in the capital has proven to be difficult. Swain said landlords have gouged apartment rents to take advantage of the fresh influx of Bahamians fleeing the devastation elsewhere.

Johnson, the woman who ferried aid to her homeland, returned to Florida last week with a heavy heart. She came back to a soft bed, air-conditioning and perhaps most importantly, a roof over her head. She goes to sleep now thinking of her family and the thousands of Bahamians who will not know these comforts again for many weeks, months or perhaps even longer. It keeps her awake at night.

But she also knows the resilience of her people. And that they will be all right.

Special Report from WUFT News

Special Report from WUFT News