4 Days, 5 Murders

Episode 2: Law Enforcement

The third murder hits close to home for law enforcement when they discover the body of one of their employees, triggering alarm in the community.

Archer Road became Elm Street as screaming headlines thrust Gainesville into the spotlight.

By Camille Respess and Chris O’Brien

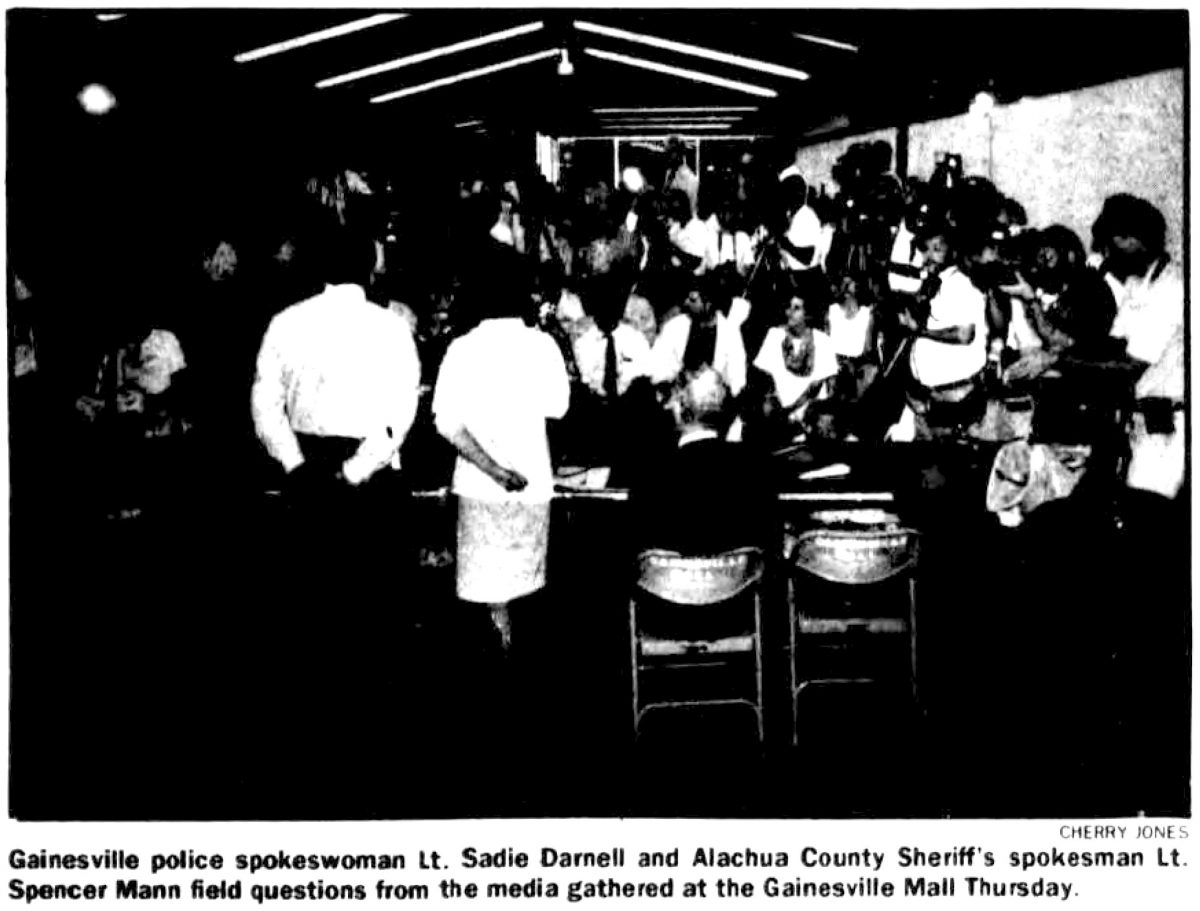

Late on a Sunday night three decades ago, Spencer Mann lounged on his living room couch and tuned into a local 11 p.m. newscast. He watched familiar faces appear on the television screen. It was Sadie Darnell, the novice public information officer who found herself fielding the most difficult of questions.

The news report centered on the bodies of two University of Florida students discovered earlier in the day in Number 113 of the Williamsburg Village Apartments, just south of campus.

Though Gainesville was somewhat of a sleepy college town and ranked the 13th best place to live by Money magazine, it was hardly immune to violent crime. A double murder, however, was rare. Mann, the Alachua County Sheriff’s spokesman, grew concerned but not overly so.

But by daylight, he knew that the city had a crisis at hand.

Sometime in the night, Mann was informed of a third killing — and it hit close to home. The victim, Christa Hoyt, was an employee in the sheriff’s office. She should have been showing up for work about the same time as the newscast to begin her night shift as a clerk. But she never made it that night.

At 12:30 a.m. dispatchers alerted police about the missing woman. They found Hoyt inside her apartment, stabbed multiple times and mutilated with a Marine issue K-Bar knife, just like the other two victims, Sonja Larson and Christina Powell.

Suddenly, the murders had been elevated to a chilling new level. And they were now deeply personal for Mann. He had known Hoyt even before she began working at the sheriff’s office. She had been a sheriff’s office explorer and made an impact with her infectious smile. Ironically, Hoyt had wanted to one day become a criminal investigator. Instead, she had become a victim.

“And so, when her body was found, not only was it upsetting the scope of the murder, but it was something personal to a lot of deputy sheriffs and to a lot of support staff,” Mann said.

Early that Monday, Aug. 27, Mann drove to the crime scene.

“It was very surreal,” he said. “The visualizations of all the crime scenes still to this day stick in my mind . . . for several months, I had bad dreams. I know other deputies that did. I’ve dealt with a lot of death over the years, been to a lot of crime scenes, but nothing that had this impact on me. So, it was a difficult time.”

He suspected the three killings were linked; that it was possibly the work of a serial killer. He picked up the phone and called Darnell.

Sadie, the big one is here, Mann said.

What are you talking about? Darnell replied.

From an investigator’s standpoint, Mann knew the grisly murders would blow up into a huge story and that he and Darnell would have to field inquiries from dozens of journalists.

We have to ramp up, gear up, because this is going to be a national story, Mann recalls telling Darnell.

In retrospect, that was an understatement. Within hours, 300 media outlets descended on Gainesville. Reporters came from Europe, Japan and parts of Latin America along with crime specialists who do nothing but probe serial killers.

“We had a logistical problem,” Mann told WUFT in a recent interview. “Where do we do briefings? Where do we place everybody? How do we try to manage information?”

The fall semester was to begin in a few hours and about 35,000 students were back on the sprawling UF campus, ready to launch a new school year. It was supposed to have been an exciting time at UF. John Lombardi had just taken charge as president in March and the Gators had hired a talented new head football coach: Steve Spurrier, a 1966 Heisman Trophy-winning Florida quarterback, who would eventually go on to lead the Gators to thrilling wins including a first-ever national championship.

But the exhilaration quickly turned dark as a cloud of fear and widespread panic drifted over Gainesville.

This was long before the days when everyone had access to instant information, long before the days of the Internet, cell phones and social media. All sorts of rumors spread through the campus community and beyond.

“We had a technology problem,” Mann said. “In order to get the word out to the media, we took an old cassette recording device for telephone messaging, and we would record when our next briefing was or if there was going to be a search somewhere or something significant and people could call that line.”

At the first press conference on Monday night, police tried to reassure the frightened public and defuse inaccurate information that was circulating throughout the community. But they also had to be careful about how much they could say.

Mann said he and Darnell were concerned about saying anything that might inflame the killer into killing again.

“The last thing we want to do is do anything that was going to contribute to anybody else’s death.”

The following day, two more students — Tracy Paules and Manuel Taboada — were found dead in their unit at Gatorwood Apartments, killed in the same grisly manner with a knife.

“Then all of a sudden,” Mann said, “within a 72-hour period, there’s five murders that took place and literally swept the rug out from under everyone’s feet and really caused a grip of fear within this community that I’ve never seen before.”

Students as well as Gainesville residents huddled in groups of 15, 20 or more at night, taking shifts to stay awake to watch over the others. Many students packed up and went back home. Some never returned to campus. The phone lines in Gainesville were jammed — so many people were calling each other, their parents, their loved ones. The Alumni Association funded a phone bank on campus so students could make long-distance calls home for free.

A serial killer was on the loose and no one knew where he would strike next.

Even the police chief, Wayland Clifton, worried so much that he put up his wife and Darnell on a high floor in a Gainesville hotel. Both women fit the descriptions of many of the victims; the killer seemed to have a fascination with petite brunettes.

“It got very personal and for the law enforcement community, of course, they couldn’t be home to protect their families because all days off (were) canceled,” Mann said. “We were working 12- to 16-hour shifts. And so, a lot of people made a decision to ship their families to other relatives . . . including yours truly.”

Many parents called Darnell and Mann, asking for advice on what they ought to do for the safety of their children. That was always a hard question. With no suspect behind bars, the right answer seemed elusive.

Gainesville transformed in meteoric speed from a quiet college town into a buzzing police state. Officials from the city, county as well as the Florida Department of Law Enforcement were all on the case. Officers kept vigilant watch around the city.

“The purpose was to stop the murdering, make Gainesville, the Archer Road corridor, look like a police state, where if you moved, there was a police officer there, so we could stop the killing,” recalled Clifton in a 2000 interview with WUFT.

Very soon, the murders landed on the front page of the Tampa Tribune, The Saint Petersburg Times and the Orlando Sentinel. And even the cover of The New York Times. Television satellite trucks lined Archer Road broadcasting the latest on the series of macabre murders.

In that first week, Mann said he fielded over 600 media calls. Many reporters asked if the Gainesville murders were connected in any way to Ted Bundy, the serial killer who, just 12 years before, had attacked and killed students at Florida State University, only two and a half hours away.

The headlines screamed: Carnage in Gainesville. Co-ed massacre. Panic on campus. One South Florida station started its newscast with this: “They used to call this Archer Road, now they call it Elm Street.”

Mann despised the hype and the frenzy that the media created. It was inappropriate, he thought.

At night, he lay down on a cot to try and rest — he slept on that cot in the sheriff’s office for the first two weeks of the investigation. But his mind churned. What would he need to do next? What would he find tomorrow? How would the police catch this vicious killer? And of course, the phones rang incessantly.

That was until Sept. 7, two weeks after roommates Sonja Larson and Christina Powell were killed, when police arrested Danny Rolling in Ocala on a burglary charge. It did not take long for forensics investigators to piece together the gruesome puzzle. Rolling eventually confessed and was put to death by lethal injection in 2006.

It has been three long decades since the Gainesville murders. Mann went on to become the chief investigator for the state attorney’s office 8th Judicial Circuit. He retired in 2013.

Not too long ago, he was eating out at a Gainesville restaurant where a longtime resident approached him.

You’re Spencer Mann, aren’t you? the person asked.

Mann answered in the affirmative, as he has always done — with a tinge of trepidation. He never knows whether he might be speaking with a person he once arrested or had a negative impact somehow on the person’s loved ones.

But this time, he realized how much the murders had become a fabric of the Gainesville community. Even 30 years later. That person remembered Mann from the fall of 1990 and said something Mann carries with him always:

“You did a good job.”

Special Report from WUFT News

Special Report from WUFT News