For one Gainesville woman, incarceration started long before she spent seven years in prison for five felonies. Now she looks to help unlock opportunities for others.

By Gabrielle Calise | April 24, 2018

Jhody Polk’s plan: Break into the bail bonds office where she used to work, empty the safe and use that money to run away to New York with her baby daddy, her 2-year-old and her infant.

But as she drives from Tampa to Gainesville to commit the robbery, her car breaks down and she hitchhikes to her old workplace. When she gets there, she breaks into the office safe and takes out $75. Thinking of the crime movies she’d seen, Jhody sets five fires around the office to destroy the footage from the security cameras.

While flames engulf the building, she looks for a vehicle to escape. Jhody figures she can hotwire her great aunt’s car, but it’s not as easy as the movies make it look. So she breaks into the house to get her aunt’s car keys herself.

Her fist pounds on the front door, and she pushes her way inside. Then she slams her great aunt down, smashing the old woman’s head against the floor and pressing a tire iron into her neck.

Towering over the old woman at 5 feet 11 inches tall, Jhody asks her great aunt for the keys and whatever money she has. The woman, crumpled into the floor, refuses.

I will kill you if you don’t give me the money, Jhody says.

She gets $120 in cash, some credit cards and the car keys out of her great aunt’s purse.

Then Jhody shoves her relative into the bedroom and wraps her hands up with phone cords. She smothers her aunt’s face with clothing and makes her escape in the stolen car.

In this 24-hour period back in 2007, Jhody has committed home invasion robbery, arson, burglary, grand theft auto and larceny. She drives back to Tampa and stays there until her grandmother calls to beg her.

If they find you, they’ll shoot you, she says. Please, Jhody, turn yourself in.

Growing up in East Gainesville in the ‘90s, Jhody struggled to find her place. She loved to learn and write poetry, but her classmates bullied her for acting “white.” The movies she watched and songs she listed to seemed to all depict blackness with the same negative stereotypes.

As she struggled with growing pains of adolescence, she also was taking care of her two younger brothers after her parents divorced.

“My sister had to raise us, we had to just cook for ourselves and do the best that we could do,” says her younger brother, Julius Irving. “We got a lot more responsibilities placed on us.”

In her early 20s, she got a good job as a licensed bail bonds agent. She had a child, then another. But even though she seemed fine on the outside, she felt like she was about to self-destruct at any moment.

“I was a prisoner long before I was even physically incarcerated. My own body and my own mind was my prison.”

Now 34, Jhody went from a seven-year-long stint in prison to using restorative justice practices to help people at the River Phoenix Center for Peacebuilding. She didn’t turn her life around until she learned to love herself in prison.

During the four years since she was released in 2014, Jhody was awarded custody of her children. She found employment and housing. This May she will graduate from the College of Central Florida and hopefully, law school will follow. She is regularly invited to speak about her life at events around the state.

“It’s the most amazing thing when you can see a person who has been so beaten down suddenly realizing that they can advocate for themselves and for men and women just like the,” says Becky Johnson, a formerly incarcerated woman who works with Jhody at the Florida Council for Incarcerated and Formerly Incarcerated Women and Girls.

Johnson calls Jhody a “dynamic community leader.” She is just one of many who sees Jhody as an inspiration and a changemaker. Yet Jhody still feels unprepared sometimes – as both a leader and a mother to her two children.

“Most people see me this way and don’t even realize that not even 6 months ago I was homeless,” she says. “Sometimes I feel like I’m not even worthy to do the work in my community because I’m still trying to just learn that work with my kids.”

Getting into the bail bonds business was Jhody’s attempt to help her little brother A.J. At 13, A.J. ran away from home and was working as a prostitute. She figured if she could start a family business like the one in his favorite show, Family Bonds, she could save him from his current lifestyle.

She took a bail bondsperson course, found an internship, and had been working for a local bail bondsman named Sam Wesley for a year. By then, she was also hooked on ecstasy. The high was incredible, but best of all the pills destroyed her appetite. Jhody had felt insecure about being overweight her whole life, and after having two kids, she was eager to lose weight. She could stop taking the pills when she was thin enough.

She only planned to take the pills for a few months — from November, right after she had given birth, to her birthday in January. But by the time January rolled around, she was strung out, popping 15 to 20 pills at a time. It was so easy to get more as a bail bondsperson. Everyone who came to see her wanted to be her friend.

She’d buy a 10-pack of pills for $100. Eat three. Stick two up her butt. Smoke another. By the time the hour was over, she’d have gobbled up the rest.

The acid from the pills ate away at the enamel of her molars. She hallucinated. She bought guns.

“I had just waged war in my mind,” Jhody says.

By then, her boss caught on that she was behaving differently. He’d noticed that she had been pocketing money.

Then she wrote a bond for Kayvonne, the father of her second child. He decided he didn’t want to go to court, and he didn’t have the money to pay her. Jhody had to make a choice — put her baby daddy in jail, or run away with him.

She picked the second option when she robbed the bail bonds office, but her grandmother’s pleading persuaded her to turn herself in.

As Jhody crawled into her bunk on her first night in the county jail, she felt like she was finally able to breathe. It seemed inevitable to her that she would end up incarcerated. Like she was born for it. Here she was.

A dual-enrolled college student with no rap sheet, Jhody figured she wouldn’t get too bad of a sentence.

“I had been in my mind, like, a decent person,” she said. “I never expected to not come home.”

After she was sentenced to eight year in prison, she reframed it as an opportunity. In prison, there would be no kids, no drugs, no man and no responsibilities.

With a record, she figured it would be hard to get a good job ever again. But she wouldn’t need one — her time in prison would earn her plenty of credibility back at home in the hood.

Behind bars with all of the killers and the mobsters, she thought, I am finally going to get my badge in the street.

She would sift out every hard, thugged-out woman in prison, and she would learn how to live like them. She would get out and rise to queenpin.

Finally, she thought. They’re going to love me.

At Lowell Correctional Institution in Ocala, the largest women’s prison in the United States, there were no Croc shoes that would fit Jhody’s size 13 feet. She shoved her toes into old smelly boots borrowed from the men’s prison. In the wintertime, she shivered in a paper-thin jacket. There were never enough bras or pairs of underwear, and the garments she received rarely fit her properly. Even the toilet paper was in short supply — officers rationed out two or three squares per inmate.

Jhody, who grew up poor and never having enough, slept on top of her sheets to avoid touching the thin cloth mattress, stained with urine, feces and blood. Asbestos and mold infested the dorms.

Jhody learned how to make do with what she had. When soap was running low, she broke up her bar and shared the pieces with the other women. She balled up whatever tissues she could find and shoved the bundle between her legs when she got her period. To this day, she still doesn’t use seasoning in her food. She learned to just go without. She was excited to make a meal out of a can of soup, a beef stick and a bag of pork skins. At least when I get home and I don’t have money to feed my kids, she thought, I’ll know how to make a meal out of a dollar.

“I remember being thankful, like at least when I get out and I don’t have nothing… at least I have alternatives,” she says.

Partway through her sentence, she was moved to Gadsden Correctional Facility, a fancy private prison where she trained to be a law clerk. Jhody made friends. She learned how to dance. For the year and a half there, she organized talent shows and parties for the women, and set up a ballot so that the inmates could vote on superlatives like biggest booty or most tattoos.

It was in there that I learned unconditional love — how could a

person love you in spite of everything that you are.

Jhody was released from prison on February 5, 2014 – one year early. She and her partner Troy moved in with her mother and her children, sleeping every night on a fold-out couch in the living room. She wanted to start a new life, to do right by her family.

Jhody didn’t feel ready to raise her kids on her own yet. She was only 21 when she’d had her first child, Devantes. She was 23 when McKennley was born, shortly before she committed her crimes.

“I had never been a mom before,” Jhody says. “I never even got a chance to be a kid and all of the sudden I have a 7 year old and a 9 year old thrown in my lap … and I don’t even know who they are.”

A month and two days after her release, she found a job working at a Motel 6—the only place she could find that would hire her with a criminal background. There was never enough money, or enough hours. She worked her way up—first as a housekeeper, then as supervisor. When she reached the point where she could hire new housekeepers, she always picked women who had criminal backgrounds.

Jhody got married and moved into a trailer, but was evicted after three months because she couldn’t pay the rent. She spent two and a half years in an Ocala townhouse. A month homeless, sleeping in her car while her children stayed with her brother Julius. Nine months in an Alachua apartment. Two in a High Springs trailer she says “was not even livable for me and my kids.” Two months living with her brother in Southeast Gainesville. Finally, in December she found a nice apartment on the West side of Gainesville.

She learned to leave everything behind but her clothes. The next place would be temporary, so she never bothered to get comfortable anywhere.

Even though she was working her way up at the hotel job, she was exhausted. With no transportation, she walked 45 minutes to work and started cleaning rooms as soon as she arrived. She got pregnant. Terrified of losing her job, she didn’t tell her boss.

“I was scared,” she says. “I had just gotten the job.”

She miscarried. She became pregnant and miscarried again.

It was hard figuring out how to be a wife, and a mother, and an employee. Shuffling from home to home.

“I would have outbursts, I would break stuff,” she says. “I would just scream all the time, ‘I’d rather be back in prison.’”

While in prison, Jhody dreamed about success. Once she got out, she just had to keep her head down. She would be fine. Things would get better.

In spring 2015, Jhody enrolled at the College of Central Florida with the dream of getting her paralegal degree. Jhody wanted to become a lawyer. To run for public office, even.

She had no idea that those things are nearly impossible for formerly incarcerated people in the state of Florida. Jhody had no idea how hard it would be to get her rights restored.

“Here I am thinking that I’m going to work hard enough and do my 10 hard years and apply, and the state’s going to be forgiving and love me,” she says.

She wondered if others who had been formerly incarcerated had been able to go to law school. Jhody’s research led her to Desmond Meade, the founder of the Say Yes to Second Chances movement that seeks to restore voting rights to nonviolent felons. Though Desmond had gone to law school after getting out of prison, he couldn’t practice law because his rights hadn’t been restored.

Up until she met Desmond, she had tried to hide her past. Then he introduced Jhody to scores of other formerly incarcerated people.

“They were not private and scared about it,” she says. “They were dressed nice, they were business owners…. And even though they were still disenfranchised and still oppressed in ways that I were [sic], they were living their dreams and they were fighting.”

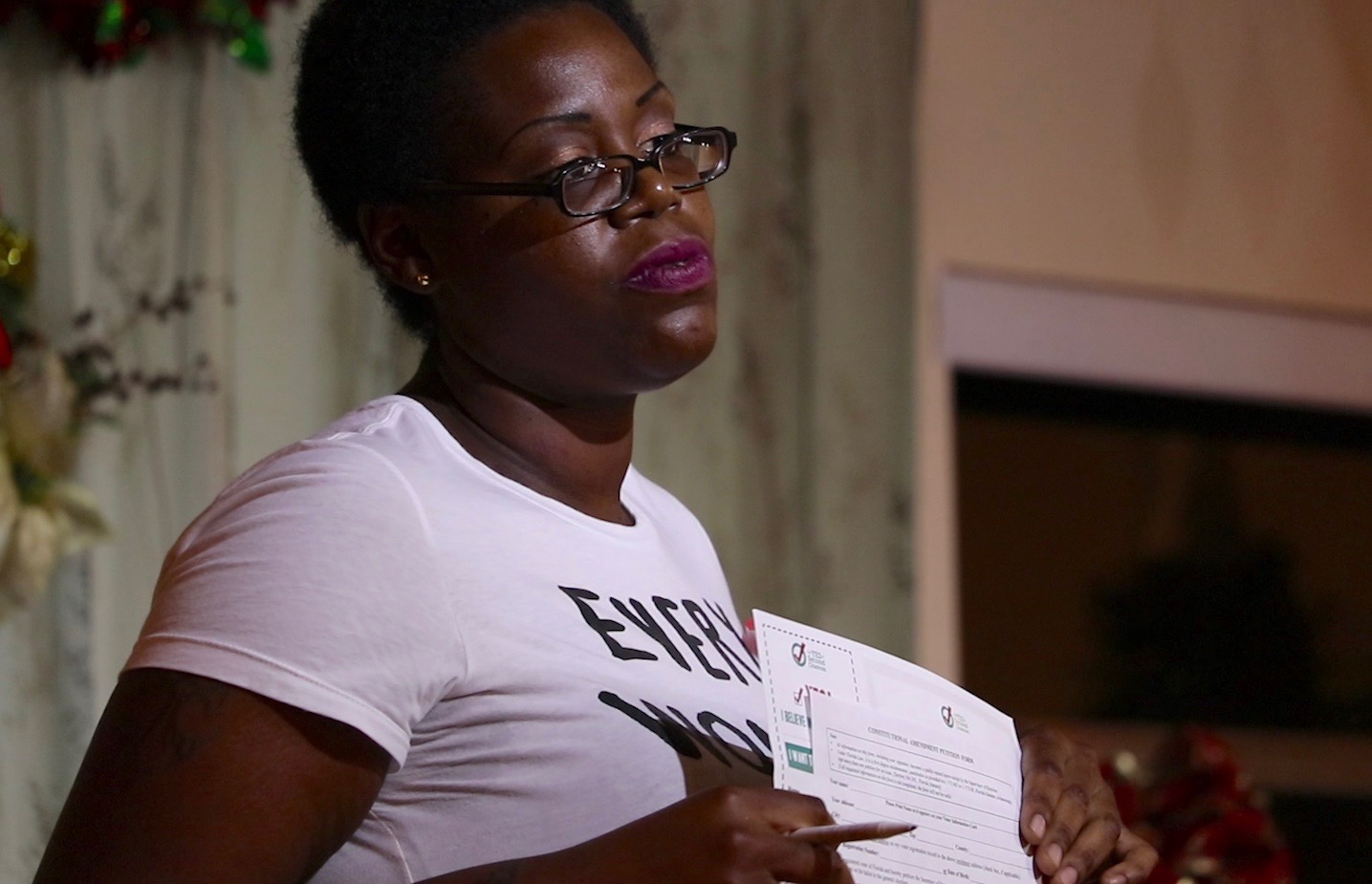

Jhody got a job as the North Florida organizer for the Say Yes to Second Chances campaign. Florida is one of just four states that doesn’t automatically restore voting rights to people with felony convictions, and the campaign sought to change that.

Jhody realized she would be able to help many people. Over 1.6 million people are unable to vote due to a felony.

“It’s like finding out you’ve got a lost brother,” Jhody says. “I’ve got 1.7 million lost brothers I have to love on.”

“Here we are fighting for second chances when most of us had never even had the opportunity for a first.”

The proposed amendment would grant voting rights to Floridians who have served their entire sentence (probation, parole and restitution included), unless the crime was murder or a felony sexual offense.

Jhody’s job was more fulfilling than working at the Motel 6, but restoring voting rights still felt like one of the least significant issues on her mind.

“Here we are fighting for second chances when most of us had never even had the opportunity for a first…we got formerly incarcerated people that can’t find a job,” Jhody says. “We had people (who) can’t get housing. I was one of ‘em. So who cared about voting?”

As Jhody excelled in community college, she kept thinking about her plans to get into the Florida bar. She couldn’t even vote. How could she get her rights to practice law or run for office restored?

Jhody had never been a guest speaker before. But the more she spoke, the more people started coming up to her and thanking her. Soon she was traveling around Florida, speaking with leaders and volunteers.

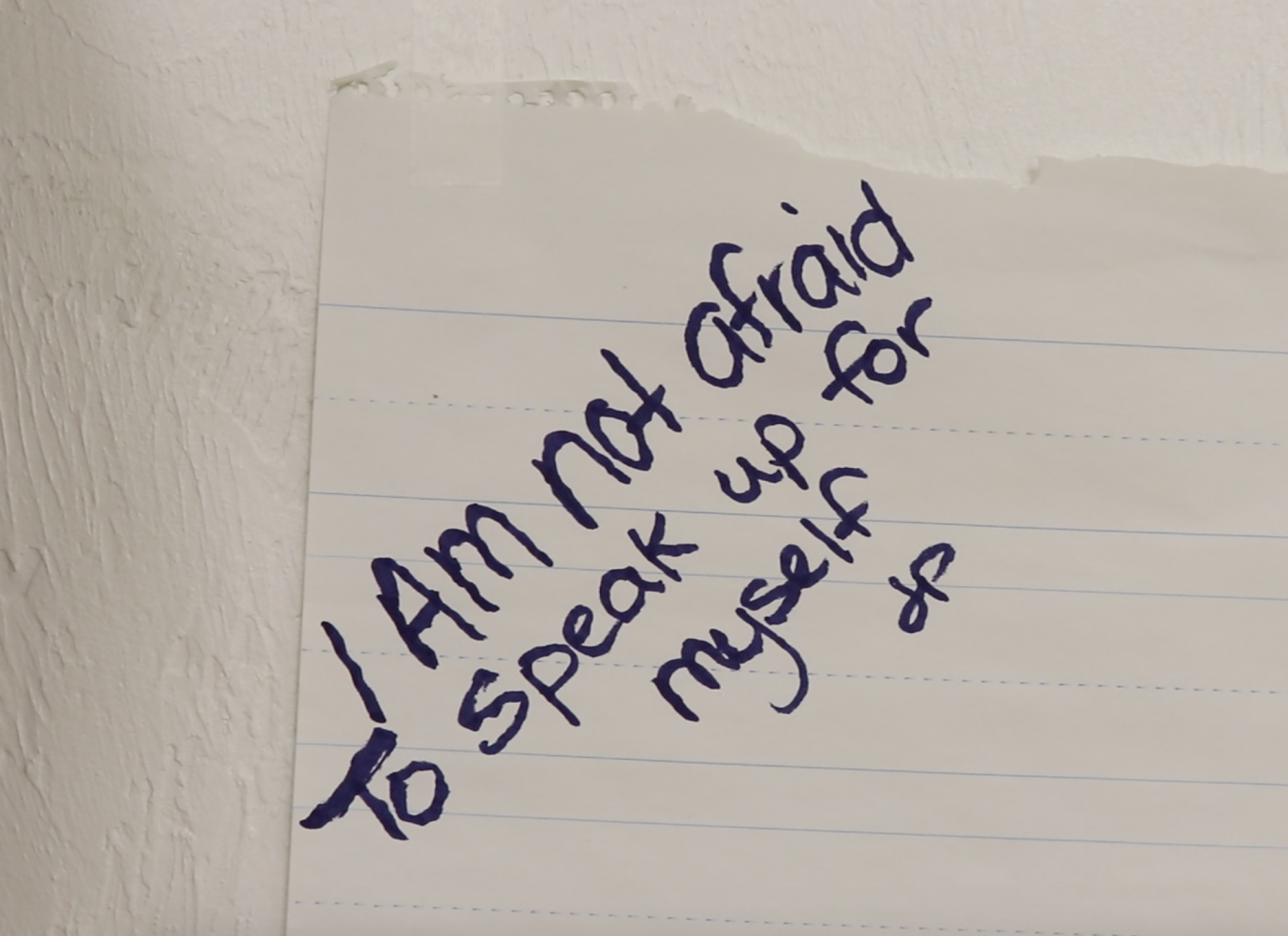

“When I learned the power of my voice and my words, you couldn’t shut me up,” she says.

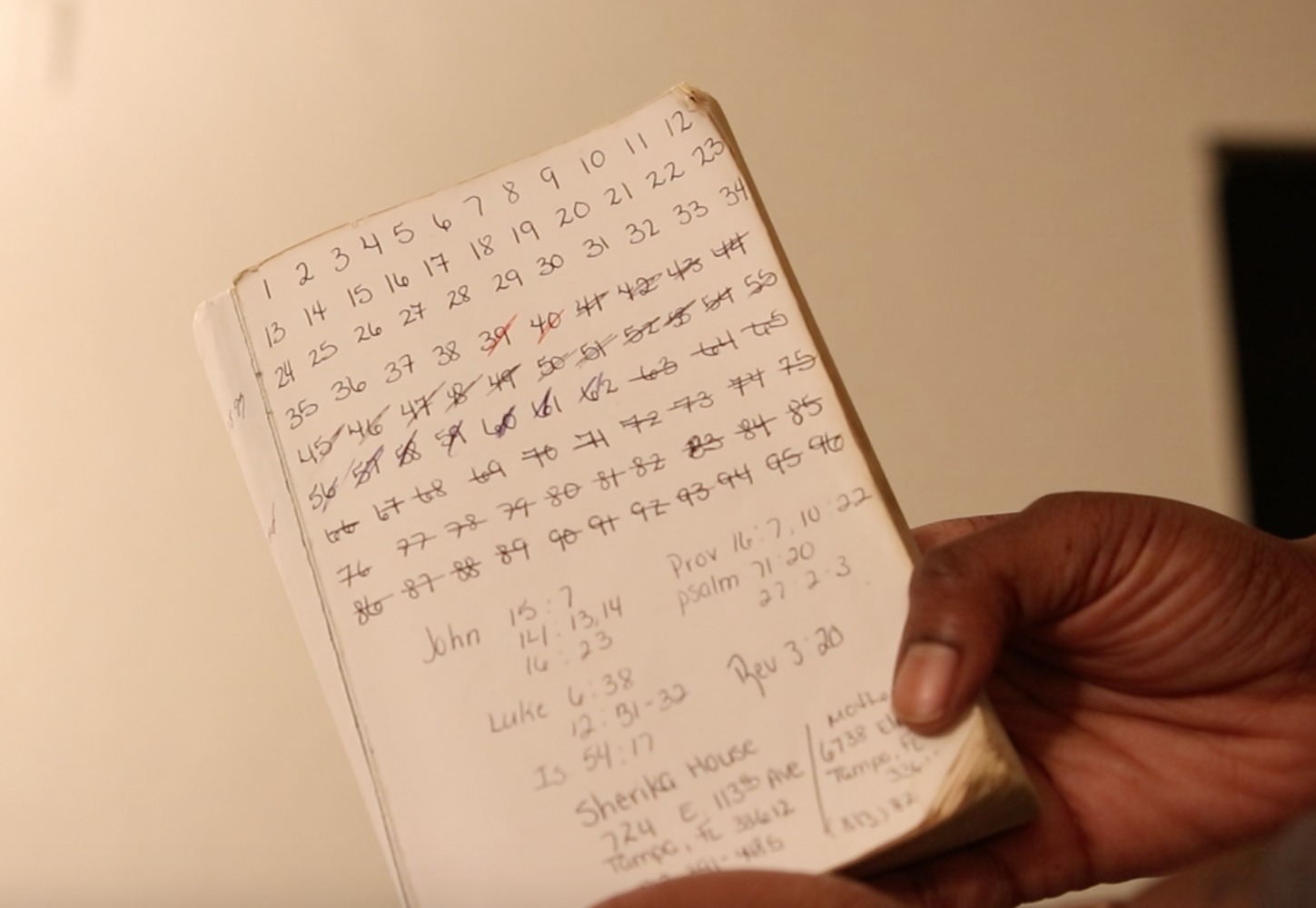

For months, Jhody shared her life story and gathered petitions. At night, she sifted through hundreds of signed petitions spread out on her couch, counting each one.

As she gathered them, thinking about the million signatures that Say Yes hoped to get, she thought more about the weight of her vote.

“I realized that my vote is important because it’s the elected officials right here in my county that really has the power that shapes the things that control my life on a day to day basis,” Jhody says.

The county commissioners, the school board, the judges, the sheriff. They all impacted her local community and her kids.

“It affects me in a way that I deserve to have a place at the table, especially now that I got my voice back and I understand who I am,” she says.

Jhody’s activism in the community also led her to run into Sam B. Wesley II, her old boss. The two now sit on a Gainesville for All committee together. He has since forgiven her.

“She still owes me money for what she did…but I think what she’s doing is good,” Wesley said. “I’d like to see everyone else come back a changed person. I don’t hold nothing against her.”

Her work introduced her to other opportunities, like working at the River Phoenix Center for Peacebuilding and meeting with members of the National Council for Incarcerated and Formerly Incarcerated Women and Girls. In the fall Jhody started the Florida chapter of the council to help other women through incarceration, and it changed the way she saw herself.

She learned the power of sisterhood. She learned how to say yes.

Yes, I am intelligent. Yes, I am a leader. Yes, I am capable.

“Our slogan is ‘Free Her’ and for the first time I realized I was ‘her,’” Jhody says. “For the first time I realized that it was ok to forgive myself.”’

To learn more about Jhody’s and six other felon’s fight to survive on the outside, read WUFT’s investigative docu-series Locked Out Florida.

Special Report from WUFT News

Special Report from WUFT News