I met Darlene Vonderlieth at a sleepy dairy festival on a hot Florida day. Amid the big-time dairy farmers with their flashy tents and flashier signs, Darlene sat alone next to a tiny wooden table, with nothing to block the sun’s strong rays.

Immediately, I wanted to know more about this woman, her emotive face and her rustic-looking booth. Before I could even get a sentence in, she began telling me about her goats. She’d come to the festival to market her business, The Holistic Goat, which sells products she makes out of their milk — lotions, facial scrubs, soaps and more.

Behind the pretty pastel bottles was a woman who worked tirelessly not only to run an entire farm, but to ensure the greatest quality of life for her animals.

Months later, I watched as Darlene trudged across a field to milk goats for the third time that day. As she milked one goat after the other, she recounted stories about each and described their unique personalities. In between, she’d check the animals’ vitals and administer vitamins, treats and other essentials.

One day, she told me of a male goat she had sold to a friend — something she takes seriously. The friend called her a week later to say she’d changed her mind about keeping it, instead planning to kill it for dinner. Darlene responded simply: “I don’t think I want to talk to you anymore.”

When a goat dies, Darlene doesn’t forget about them. They live on in her tears afterward and the stories she tells about them years on.

While her farm barely turns a profit and Darlene lives paycheck to paycheck, she finds solace in her goats. Together, they form a bond, which Darlene promises for life.

Darlene Vonderlieth stares out across her Live Oak, Fla., farm, Zeigekase, named after the German word for goat cheese. It all started with a Hobby Farms magazine article predicting goat farming to be the next big trend. “I thought they were stunning,” Vonderlieth said. “And I just wanted privacy with the animals, to have a large piece of land where I wouldn’t have any neighbors or hear any horns.” The photo was taken in February, 2020.

One of Darlene’s 58 goats, each with their own name, stands in her living room, a thick layer of hay coating the floor. During the winter months, Darlene lets younger goats sleep in the house to prevent them from falling ill. She inhabits and maintains the 10-acre farm on her own — besides the unexpected visit from her ex-husband Mike once every month or two.

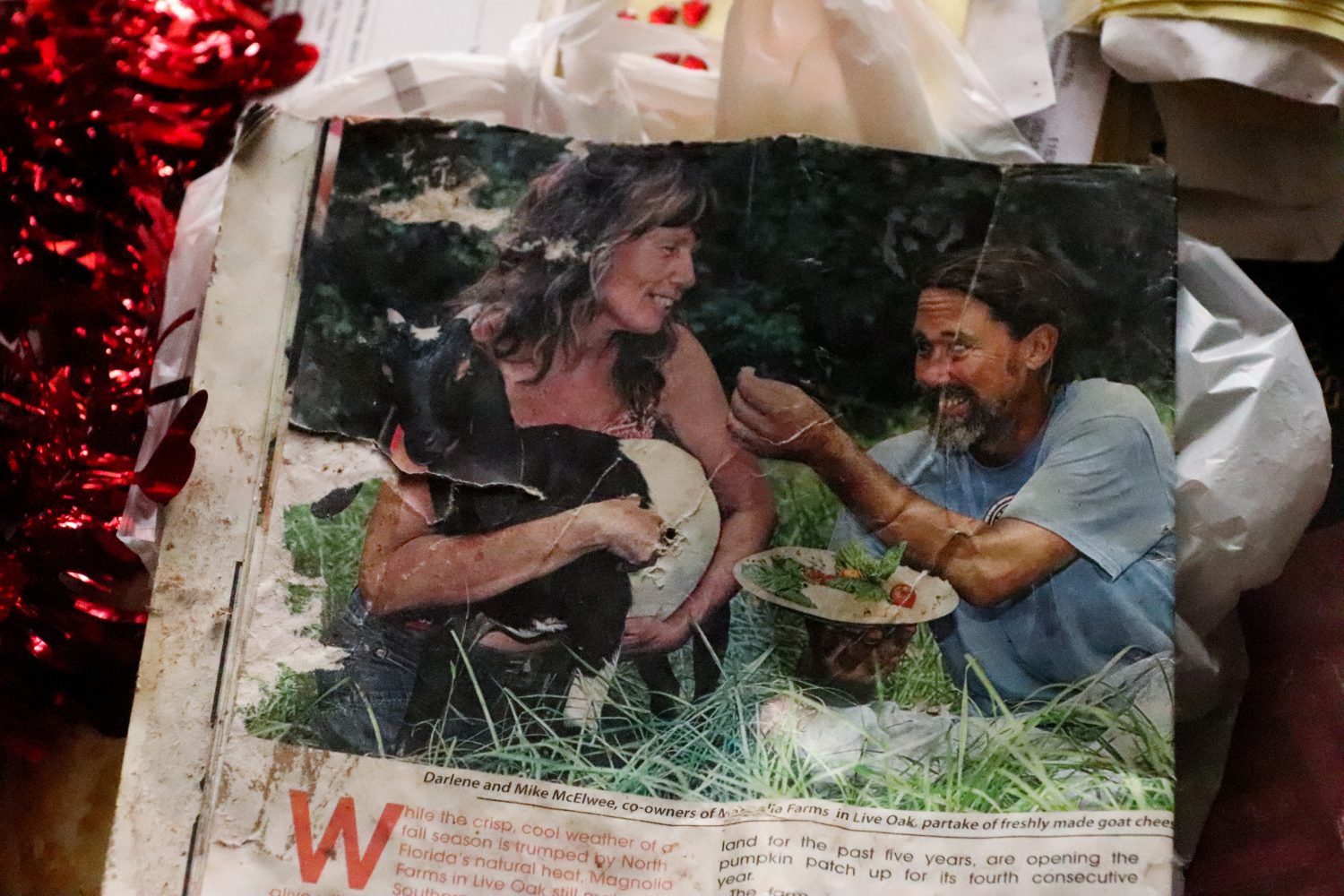

A magazine clipping from the early 2000s shows Darlene and her ex-husband smiling together on their first property in Live Oak, called Magnolia Farms. He grew tired of the 24/7 demands of the farmwork fast, but Darlene never did, she said. Despite having to work from 4 a.m. to nightfall each day, she said her goats need her and she could never turn away.

Darlene sips water in her kitchen, a single yellowed lightbulb lighting the room. “People have hurt me a lot,” Darlene said. With her goats, though, it’s different. “I can see it in their eyes they appreciate what I do for them. They’re just so proud,” she said.

Darlene places a unicorn-themed headband on one of her goats. In between milking sessions on a rainy Valentine’s Day, she dressed the animals up in festive accessories to brighten the holiday.

Darlene stares out the window of her milking shed, where she must milk her numerous goats four times each day. The 59-year-old said it’s become difficult to maintain the farm’s operations by herself. In addition to daily labor, she must market her organic, raw goat milk, which she uses to make cheeses, lotions and facial scrubs.

Darlene struggles to budge a heavy gate open, as her guard dog watches. Still, she doesn’t complain out loud. Instead, she laughed it off. “You gotta really love something or someone a lot to do s*** like this every day,” she said.

Darlene walks her goats out to the feeding pasture. Wherever Darlene goes, the animals are usually close behind. “Oh, just wait one minute! I’ll be right back,” she’ll yell to the goats when leaving them, their calls beckoning after her.

Darlene looks off into blank space while milking a goat one of many times that day. At moments, she’d wonder aloud when her ex-husband might pay a visit next. More often, she’d ask what would happen to her goats without her there. “I hope for God’s sake when I die, I come back as a goat and someone kisses my ass like I kiss theirs,” she said.

Special Report from WUFT News

Special Report from WUFT News