While states have reacted quickly when it comes to school gun violence, the federal response has trailed far behind.

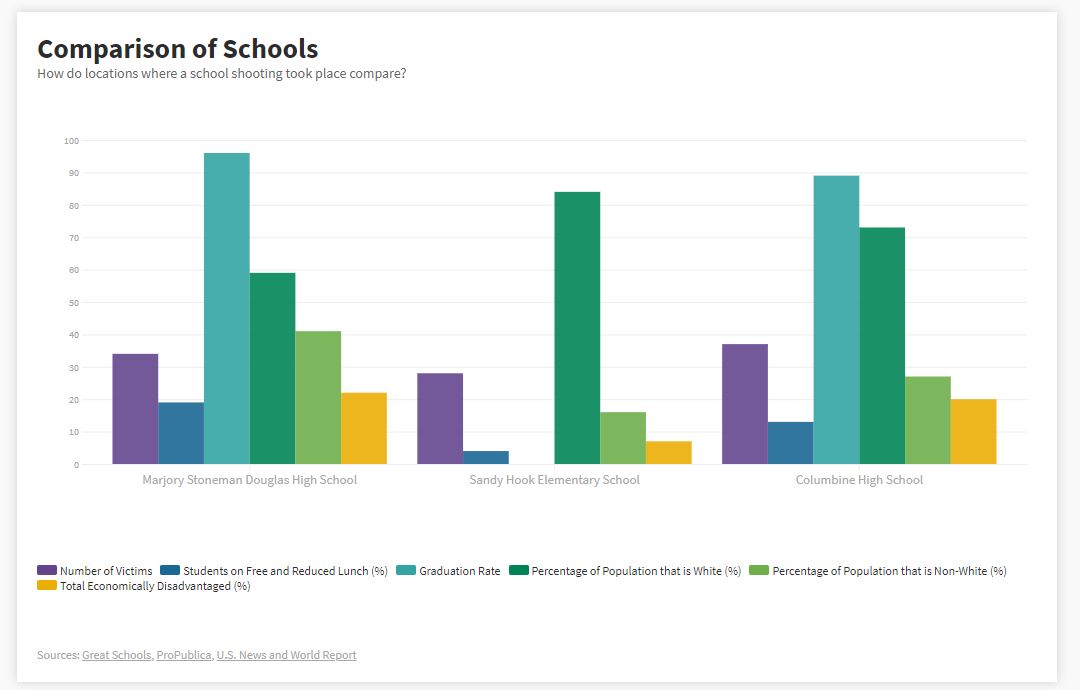

Despite being more than 2,000 miles apart, Columbine High School in Colorado and Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Florida have several things in common.

Both school populations are predominantly white. Less than a quarter of the total student body population is considered economically disadvantaged, and less than 20 percent of students are on the free lunch program.

Both schools were also the site of a school shooting and neither school fits the stereotype of an “unsafe” school.

Brookings Institute’s Senior Fellow and Director of Education Mike Hansen explains how school shootings have altered how experts view which schools are safe.

“Oftentimes we view school safety issues through a very racialized or socio-economic lens, where we look at schools that serve large proportions of students in poverty or large proportions of students of color,” Hansen said.

Hansen said school shootings have happened in schools that “are predominantly white and have higher levels of socio-economic status.”

Parents, who never worried about their child’s safety at school, are now full-fledged activists for reform in the wake of these shootings. These activists have pushed new laws and policies at the state and the federal level.

Twenty-three days after the Parkland shooting, the Florida legislature passed the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School Public Safety Act.

The law raised the minimum age to purchase a long gun from 18 to 21, extended the waiting period to purchase a firearm, banned bump stocks, made school safety officers mandatory and created a path for arming teachers.

Parents, community members and students have pushed to get laws passed after mass shootings occur.

Their efforts are not always successful.

Forty-two days after Sandy Hook, the Assault Weapons Ban of 2013 was introduced to the 113th Congress. The bill failed to pass by six votes.

“At the federal level, I feel like there has been more talk but very little action,” Hansen said.

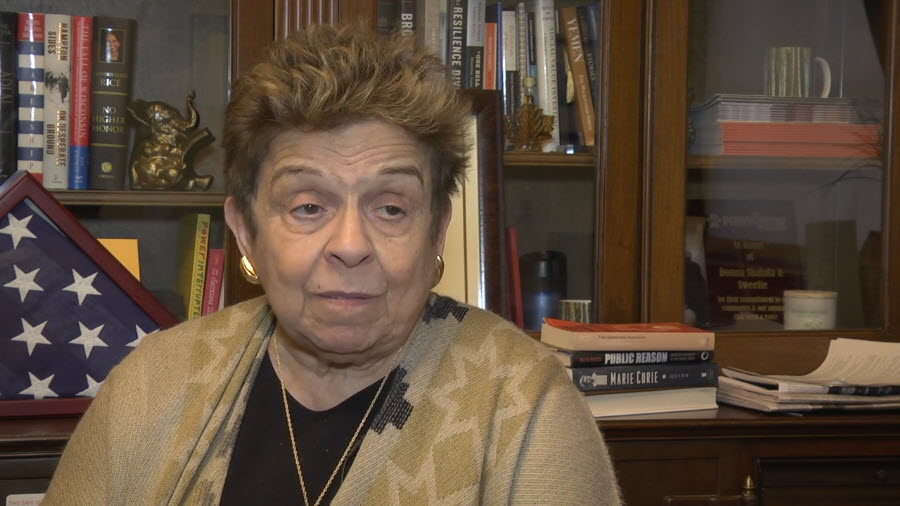

U.S. Representative Donna Shalala, D-Fla., said the absence of significant gun reform is not from a lack trying.

Shalala is familiar with the challenges policymakers face when attempting to pass stricter gun regulation. In 1994, the congresswoman was part of the team that pushed the assault weapons ban during President Bill Clinton’s administration.

She blames the absence of federal gun control legislation on the lack of bipartisan effort.

“Democrats are willing to do it,” Shalala said. “Democrats are listening to their constituents. The vast majority of constituents believe in background checks. They also believe in an assault weapons ban. That’s not reflected by their representatives.”

Congressman Ted Yoho, R-Fla., said the issue is not partisan, rather the debate boils down to one central issue: the right to bear arms.

Yoho said it would be “a very dangerous thing” to pass legislation impacting the Second Amendment.

“If you start whittling away at the Second Amendment, does that give right and cause or precedents to whittle away at the First Amendment?” Yoho asked.

Yoho said policymakers should look to local governments to determine the needs of individual schools. He said he does not believe passing blanket gun control policies will end school shootings.

The congressman’s argument is mirrored by the Federal Commission on School Safety. In March 2018, President Donald Trump established the Federal Commission on School Safety under U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos. The commission was tasked with determining how to keep students safe.

On Dec. 18, 2018, the commission released its final report. A letter from DeVos to the president was included detailing the commission’s official conclusion.

In the letter, Devos writes that there is not one solution that would work for every school.

“What may work in one community may or may not be the right approach in another,” Devos writes.

She instead recommends that the responsibility fall to state legislators rather than the federal government.

“Ultimately ensuring our safety begins within ourselves, at the kitchen table, in houses of worship, and in our community center” Devos writes in the letter.

The commission concluded that school safety measures are most effective when they are based on the needs of individual schools and not generalized at the federal level.

Currently, each state has different levels of gun laws.

The above visual demonstrates whether each state allows closed carry and/or open carry (licensed or unlicensed), as well as if the state has some form of background check system, firearm registry or waiting period. Additionally the gun laws of each state are given a letter grade by the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence and a rating out of five stars from Guns to Carry.

The first federal response to decades of school shootings passed the House this year.

The Enhanced Background Checks Act was recently introduced in the Senate.

If passed, this piece of legislation would give the FBI more time to perform background checks before gun purchase.

But it must pass the Republican controlled Senate first.

Up next: International Changes »

Special Report from WUFT News

Special Report from WUFT News