By Molly Donovan | December 4, 2017

For kids in East Gainesville, failing third grade can be a prison sentence. It’s a cycle of poverty, so the School Board, police and other educators are trying to figure out how to stop it.

Every day, Michele O’Neil wakes up and prays.

She asks God to carry her through another 10 hours in her classroom. To help her see past the things she can’t change. To give her strength to try anyway. To remind her that the love she has for the kids outweighs the hopelessness she sometimes feels trying to make their lives better.

O’Neil does rejoice in the successes. When one of her third-graders finishes a book or turns in homework, she knows that she’s making a difference.

But most of the school, and most students in East Gainesville, are grade levels behind in reading, arrive to school with no lunch and every now and then tell teachers how much they hate white people. Every day, O’Neil and other teachers are working to help students break free from a trajectory of failure.

“I’m giving everything I have,” O’Neil said, “but you can never really do enough.”

In schools on Alachua County’s East side, a predominantly black area, students are living in this cycle: They underperform in school, which is connected to more minors getting arrested, which leads to a much higher dropout rate. Those who drop out of school? They make up most of the city’s gangs.

To decrease crime and dropout rates, as well as improve economic situations for families, community leaders say that solutions need to start with test scores and educational success. The School Board, Gainesville Police and after-school programs are using relationship-based initiatives to stop the cycle, but they all say that solutions are easier to discuss than to actually carry out.

In May, the School Board created an office for Educational Equity and Outreach and has devised a plan to monitor test scores in each district. Literacy groups work daily with students who need to catch up. The Gainesville Police department focuses on eliminating minor arrests.

The hope is that year by year, the dominoes—poor test scores, arrests, droputs, and poverty—will be eliminated one at a time.

“I want so badly for these kids to be successful,” O’Neil said. “I’m discouraged, but then I wake up and it’s a brand new day. I can’t focus on the negative. We literally won’t make it if we do.”

I can’t focus on the negative. We literally won’t make it if we do.

For the 2016-2017 school year, only 20 percent of students at Rawlings passed Florida standardized end-of-year tests, according to data from the Florida Department of Education. Rawlings was one of four Alachua County schools to rank on the list of the 300 lowest-performing elementary schools in the state last year.

Every year, state prison officials look at what third-graders score on these exams and use the scores to predict future inmate populations.

Children who can’t pass are slated for a prison cell – at 8 years old.

“They say third grade, but it really goes back to kindergarten,” said Will Halvosa, Gainesville Police Department’s disproportionate minority contact coordinator. “You’ve got some kids that come in already reading and other kids that don’t know their ABCs.”

This national trend is the basis for the School-to-Prison Pipeline, a phrase used to describe a mass incarceration of minorities, specifically those 17 and younger.

“There’s so much more actually going on than people realize,” O’Neil said. “It’s happening in our city. Care about that.”

A Catalyst for Change

In his desk at his office, Officer Will Halvosa has a stack of McDonald’s coupons thicker than most textbooks. He thumbs through them, pulls out a few for a quarter-pounder with cheese, then rubber bands the stack back together.

Every week, he gets lunch for and eats with a group of students at Lincoln Middle School. He’s been with the Gainesville Police Department for 33 years, and for the last four, he’s served as the disproportionate minority contact coordinator, focusing on the School-to-Prison Pipeline and its prevention in Alachua County.

“When we embarked on this a few years ago, we took a step back and realized, ‘Hey, 90 percent of the kids we’re arresting are black,” he said. “Why is that? And we realized it’s a very tough question to answer.”

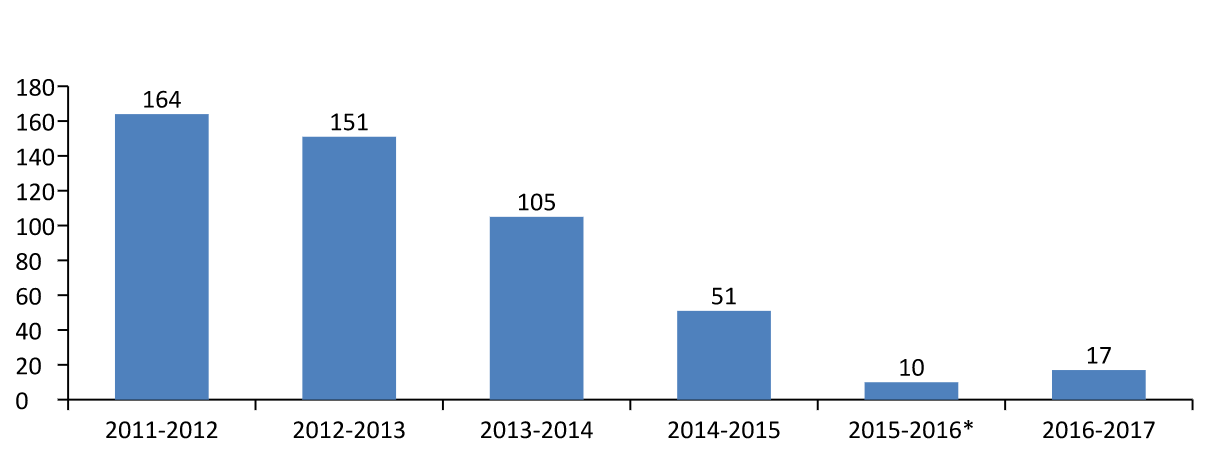

Halvosa started with the data. In 2013, Alachua County had the highest rate of minorities being arrested in the entire state, according to the Florida Department of Juvenile Justice. Of the 1,460 juvenile arrests that year in the county, 80 percent were black.

“Because of our history in this country and in the south, we’re way behind,” Halvosa said. “I looked at the disparity numbers and realized what needs to be done. That’s where I work. That’s what I have the most control over.”

His team looked at the juvenile arrests and realized that the majority were kids on probation who were suspended from school. The system, he said, was set up to fail.

Kids on probation who are suspended are often arrested because school is a term for their probation. Those who are expelled are sent to alternative schools, like A. Quinn Jones Center in Gainesville, where 100 percent of the students are economically disadvantaged, according to the Florida Department of Education.

Discipline isn’t necessarily a bad thing, Halvosa said, but furthering the arrest cycle of children is.

“I’m not saying there doesn’t need to be accountability and consequences,” he said, “but it’s not going to be done through handcuffs.”

Halvosa and his team pushed for a new initiative within the police department. Officers who respond to calls regarding minors are instructed not to cuff a kid unless a violent crime is committed – especially in school.

In addition, GPD has partnered with other organizations, like the Alachua County School Board, to develop “System of Care,” an all-encompassing focus on providing multiple services for families in need.

Eileen Roy, the board member from District 1, said it’s difficult to fund all the things necessary to sustain successful programs like the Manning Center, which serves as a facility for “in-school” suspensions instead of the alternative – sending kids home, which breaks their probation and lead to arrests in the past. The Center is staffed with a full-time instructor.

The system includes a committee that meets once a month to discuss how to provide the services like counseling, transportation to school and events for families.

The system has also given Rawlings Elementary the ability to hire more teachers in the last few years and to create a focus on the arts. And the efforts seem to be helping: From 2015 to 2017, the school’s grade rose from an F to a C.

“Oh my gosh, you should go see these kids perform,” Roy said. “They’re amazing.”

For now, the program is funded by a grant from an anonymous donor, who gave $1.5 million over three years for counseling and family services. When that runs out, Roy said she’s not sure what will happen.

“This is going to save lives, honestly, because it’s counseling for the parents and children, and it leads to better attendance, better academic achievement – all of those things,” Roy said. “But we don’t have money for all the extra services we’d like to offer, because we barely have money for the basic things we need on a day-to-day basis.”

In 2014, there were 464 citywide juvenile arrests, according to Gainesville Police Department data. Four hundred and twenty of those were black youth. In 2017, the number of juvenile arrests dropped to 228 — 183 were black.

Things are changing, said Officer Halvosa, but it won’t happen overnight. So for now, he’ll focus on building relationships with his middle schoolers and showing them that he cares, one cheeseburger at a time.

“I feel like we’re going to make some changes,” Halvosa said. “I feel encouraged by our data and the things that we’ve done. It’s a slow process, but we’re pioneers.”

Room to Grow

Down the street from Rawlings Elementary, in the 70-degree afternoon sun, a second-grader lays face up in the grass, his eyes closed. The hood of his black Batman jacket covers his head, and except for the occasional wiggle of his sock-covered toes, he is still.

His maw-maw, Tanya Gribble, watches him, her head resting on her closed fist.

“This is a rare sight for me,” she said. “He’s never this calm.”

Three years ago, Gribble moved to Gainesville with her grandson, Dashawn, from Georgia to help her daughter care for a new baby, Dashawn’s cousin.

She came to help because she remembers being young and alone, trying to parent her daughters. She worked 80 hours a week as a manager at Huddle House and did what she could to take care of her family.

“My mother raised four of us by herself, and we were working in orange groves by the time we were Dashawn’s age,” she said. “When we got old enough, she wasn’t there for us anymore. It was like she could finally breathe. I want to be there for my babies and grand babies the way she wasn’t there for me.”

When Gribble arrived in Gain

esville, she enrolled Dashawn in Kids Count, an after-school literacy program that serves Rawlings and Joseph Williams Elementary School. The program became one of the few places that Dashawn, who was recently diagnosed with autism, looked forward to going.

“He had so many meltdowns at the beginning, and he hates being in the grass,” Gribble said, watching the twitch of Dashawn’s peaceful toes on the program’s playground. “But this is a safe space for him now.”

Keri Neel, the executive director at Kids Count and O’Neil’s twin sister, said the goal of Kids Count, which serves first- through third-graders, is to get students reading on grade level by the time they leave.

“If a child isn’t on grade level by third grade, they only have a one in seven chance of ever catching back up,” she said. “It’s really overwhelming knowing that that’s the trajectory that they’re on.”

Kids Count also works to build relationships, help students with homework and to develop social and behavioral skills. Neel said the relationships make more of a difference than anything she’s seen so far.

“These kids have so much potential,” Neel said, “and the best part is seeing them reach that.”

She remembers meeting Dashawn her first year working for the program. He constantly told her ‘no’ and had regular, uncontrollable meltdowns.

“He would just start crying for 30 minutes straight, and we wouldn’t know why,” she said. “There were moments with him when I thought, ‘We can’t do this; he won’t be able to stay here.’”

Eventually, the staff started to learn the things that triggered him and to understand his behavior. Neel met Gribble, and they talked constantly about ways to help him. One day at a time, he started getting better.

“His teacher reached out the first time he ever turned in his homework,” Neel said. “He was so proud and just so excited to bring something to class that he had done.”

Neel said there are a hundred other kids like Dashawn who just need the extra push and the extra time commitment, but Kids Count can only do so much. There are dozens of students on the waiting list because of limited volunteers. There’s a constant need for more funds, more space and more people, she said.

“It feels like we’re on our own sometimes,” she said. “I love this job. I wouldn’t trade it for the world. I love the kids. I love the parents. I just wish we could do more.”

Neel knows that outside her program, there are kids she can’t help, and like many others, she gets overwhelmed with the scope of the problem.

“People hear all the statistics, but when you know kids that are in these situations and you know the reality of what it means when a kid isn’t on grade level and the cycle will continue with them,” she said. “When you can put a face to the statistic it just really changes everything.”

But frustration won’t keep her from loving the kids, and it won’t keep Gribble from giving everything she has to Dashawn.

“I worry about his future,” Gribble said. “I want him to go to college. I want him to succeed.”

The culture of the city, she said, is to keep pushing for change, no matter what. And she feels the same.

“I’ll fight for him,” she said. “Always.”

Special Report from WUFT News

Special Report from WUFT News