Gainesville begins dismantling an encampment that had become a ‘broken piece’ in a system of care.

When a homeless encampment is shut down, one woman fights to find home.

In one Florida city, strict policing pushes homeless population out.

A homeless woman helps make sure others don’t stay invisible.

Voices from the Village

The people who call Dignity Village home

share their stories

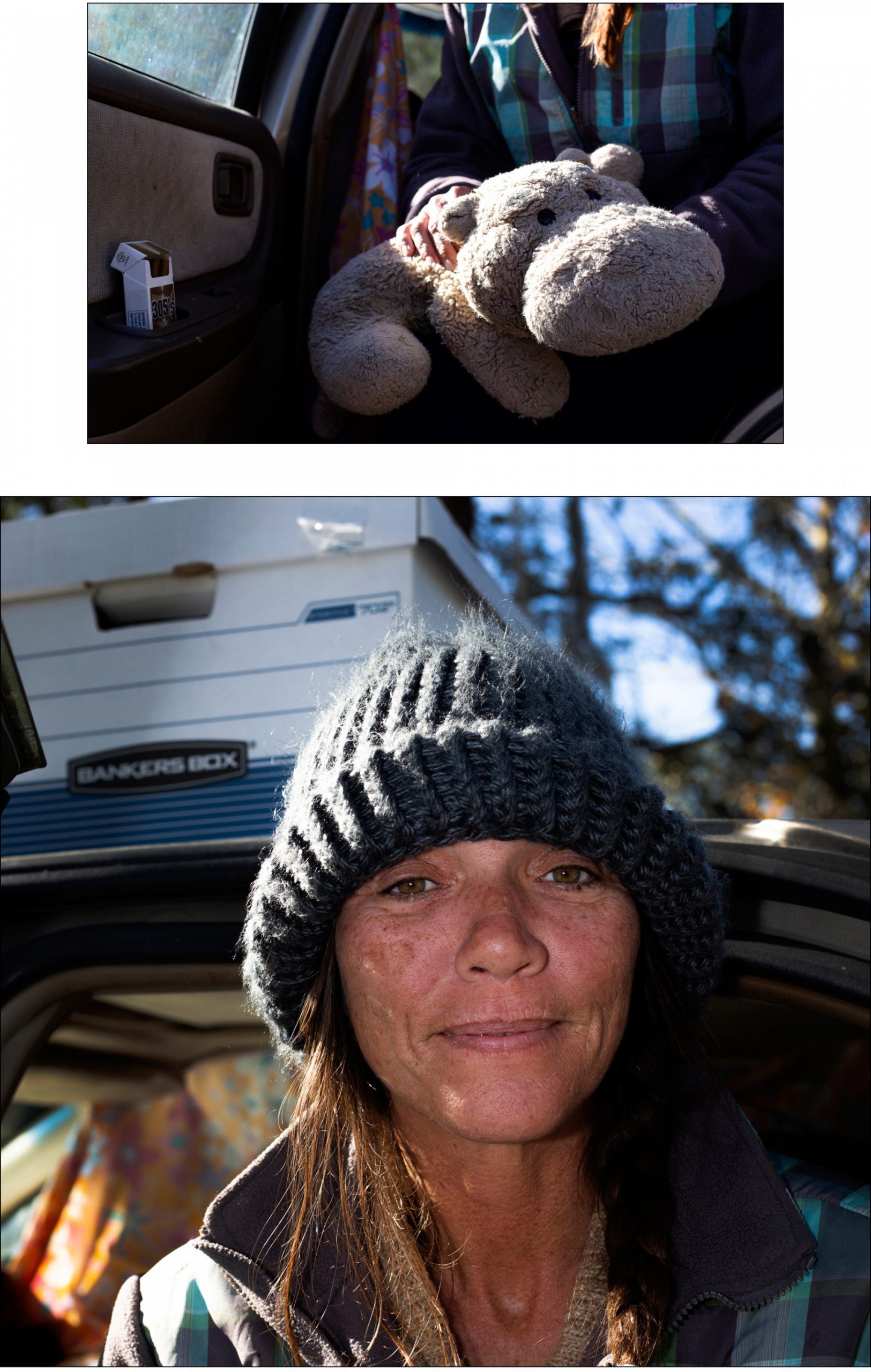

JENNIFER

When a beat-up Nissan is home and a garden gives solace

By Edysmar Diaz-Cruz

When Jennifer Pytlik wraps herself with layers of blankets in the backseat of her car, she closes her eyes and imagines a life in which she is no longer homeless.

In this life, she gets to take her granddaughters, Elise and Adaline, to the playground and watch them laugh and run carelessly, as children do. She gets to learn how to play the piano alongside them. And when the girls grow into teenagers, they come to Jennifer for advice on boys.

But then Jennifer opens her eyes. And reality sets in.

Her days begin in her 20-year-old gold Nissan Altima, parked in a lot at Dignity Village. The tires are deflated and the engine refuses to sputter back to life. The stagnant seats hold the last of Jennifer’s “possessions ” — neatly folded clothes, family albums and a collection of self-help books. The car anchors her to what she sees as purgatory on Earth.

“The people here love drugs and drama,” she says. “I just want to get out.”

At 49, this is what her life has come to.

Every night, she fears thieves who lurk in the dark, slashing neighboring tents and disappearing with what little everyone owns in this tent city. She can hear them rustling outside of her car window.

She once watched a woman who had been homeless longer than herself reach a breaking point after consecutive nights of looting. At the sight of her dwindling pile of clothes, which she hid under a black tarp, the woman threw herself onto the remaining heap and cried. She swore to anyone who cared to listen that the thieves would pay for taking what little she had left.

The woman screamed and shook her fists at God. “All I do is give, give, give,” Jennifer heard her say, “And what do I get? They take, take, take. I’m ready to walk out on this life.”

Jennifer watched the woman from her car five feet away. She couldn’t bear the sight of her suffering.

“No, honey, you don’t want to do that,” she told her. “Don’t take the easy way out.”

Every night, Jennifer locks her Nissan and hopes for the best.

She turns to her stuffed hippopotamus. She runs a blue comb through the fake fur. It helps calm her nerves.

“It gives me something else to do with my hands besides smoking,” she says of her daily half-pack of Marlboros.

Besides, the toy hippo reminded her of Leo, the cat she left behind in Milwaukee before moving to Gainesville nearly two years ago to be close to her only daughter. She found a job as a housekeeper for a married couple. In exchange for her cleaning services, Jennifer was able to live in the couple’s guest house for several months.

But then the pain from a previous factory job injury returned and got in the way of her work. She was let go. She packed her belongings and ended up at the GRACE Marketplace shelter, where she hoped to take a cold shower and enjoy a free meal.

But it was hard to sleep amid the chaos in the shelter dorms. Then her car engine blew out on the way back from a trip to a nearby convenience store. And her phone was stolen. She lost contact with her daughter.

“I miss being a productive member of society,” Jennifer says. “For most of my life I was going to work, I was making things happen

I was earning a paycheck. When I needed things, I could go shopping. When my muffler broke, I could go to the mechanic and fix it.”

Jennifer now has to panhandle to afford simple luxuries from her past life, like an occasional Diet Coke. She spends hours standing on a median as cars zoom past her. On average, she makes $8.

“It smells, it’s loud and it’s degrading, but I refuse to sell my body,” she says.

Still, she managed to establish slivers of normalcy in her life as a homeless woman. She tends to a flourishing 2 by 6 plot of land in a community garden, behind the shelter cafeteria. On sunny days, she puts on her maroon sunglasses, throws her purse over her shoulder and checks on her jalapeños and tomatoes.

“It’s a place for me to feel like myself again,” she says, “and enjoy some of the things that I love about myself.”

She dedicates hours to pulling out weeds that invade her garden. The fence that separates it from the tent city blocks her view of the place where she is forced to live. The only hint is the smoke from campfires rising to the sky. Here, in her garden, she feels most like the woman she used to be.

RAMONA

A couple’s decision to move rests on the love of their canine companions

By Edysmar Diaz-Cruz

Underneath a canopy of trees, a dirt path leads to a makeshift home. An American flag marks the entrance and a yellow diamond-shaped sign issues a stern warning to all guests: “Pitbull on Guard.” The slightest sound, like the crunch of fallen leaves, sets off a startling yet effective alarm system. A cacophony of barking, deep and protective in tone, alerts Ramona Seay and her fiancé, Keith Ratchford, of the presence of others.

Every morning, Ramona emerges from the home she and Keith built in the woods and greets their six pit bulls: Buddy, Storm, Mary, Twister, Razzy and Legend.

The couple dedicate their lives to rehabilitating abused and malnourished dogs in Dignity Village. While canines are loyal companions to the homeless, sometimes they get left behind. Ramona and Keith built a fence out of wood pallets and metal wires to keep their dogs safe.

“We’ve built our own castle out here,” Ramona says, looking at her campsite. Each dog has a tent that shelters them from rain and sun.

Taking care of the dogs takes up two hours of Ramona’s morning routine. They must be fed, walked and entertained. Some dogs require socializing to calm their aggression while others require physical therapy for their ailing joints. Afterward, Ramona tackles her daily to-do-list. It’s a long one and Ramona can’t afford to rest until she’s done.

Being homeless can be hard work.

She rides her bike to Walmart, where she buys groceries and dog food. She collects silver trinkets and other junk scattered around the Dignity Village compound to sell at secondhand stores. At the GRACE Marketplace shelter, she and Keith collect water in empty milk jugs and take them back to their campsite for cooking, washing the dishes and bathing their dogs.

On laundry day, Ramona ties three trash bags full of clothing and stacks them onto a shopping cart. She’s a petite woman with thin arms, but her biceps bulge as she lunges forward to keep the wheels from getting stuck in the earth. She brushes her black, curly hair away from her blue eyes and pushes the cart up a hill and out of her campsite. As she nears the community laundry room, she angles her shoulders for one final thrust, forcing the cart through a hole in a fence that separates the tent city from GRACE Marketplace.

By then end of it all, Ramona is out of breath.

The sun hangs low when she finally returns home for dinner with Keith, who jokingly insists that she eats like a 300-pound woman. She attributes her massive appetite to her high metabolism, but Keith is convinced that she simply loves to eat. Ramona does not deny this. She looks forward to dinner and is proud of the meals she makes. At Christmas last year, she made a chicken pot pie from scratch, slowly steamed over a fire. On days when they can only afford canned foods, Ramona closes her eyes and tries not to think about it.

Legend is usually the first to greet Ramona when she comes home. He barks incessantly, baring his teeth and gums while tugging on the rope that keeps him bound. The muscles underneath his grey fur make him look large and threatening.

“Aye! You can’t bark and wag your tail at the same time,” Ramona says.

Ramona found Legend tied to a pile of trash in the woods, and he had trouble walking on his own. She suspected he had severe hip dysplasia and spent several months massaging his joints. Now that his pain has faded, he greets her with his whole body.

After three years, Ramona has lost count of the number of dogs they’ve nursed back to health, including a litter of puppies. She welcomes all kinds of breeds but loves pit bulls in particular. They are misunderstood. People, she says, can learn a lot from them — strength, perseverance, unconditional love.

“These babies are my calling,” she says. “These guys do not have anybody to stand up for them. It’s what God kept me here for.”

She likens her household to a farm. Every once in a while, she and Keith lead the dogs deep into the woods and allow them to roam free. They chase deer and foxes. And they love to swim.

The thought of parting with the dogs breaks Ramona’s heart. The dismantling of Dignity Village means many residents will have to move into an enclosed compound in the GRACE compound. Ramona and Keith had to think hard about where they would go. How would they possibly move inside if it meant taking away their dogs’ freedom?

Luckily, a friend offered them his truck and the couple plan to move to another plot of woods elsewhere in Gainesville. They hope to recreate their campsite there.

“We don’t always agree on everything, but in the end, we always get it done,” Ramona says.

As Keith starts taking apart the fence, Ramona feeds the dogs. Their to-do-list only grows longer, but it’s worth upending their makeshift home if it means they get to keep their canine friends close.

TATIANA

The thin line between homelessness and not: A Greyhound bus ticket

By Edysmar Diaz-Cruz

The nightmare began almost a year ago when Tatiana skipped school.

Scared to face scheduled tests, she instead spent the day at a Boca Raton mall and then headed to the beach with her friends. When she came home, her parents put her on lockdown. Upset, Tatiana packed her belongings and left.

“I begged her not to,” says her mother, Laurie Garcia. “But she was hell-bent on doing it.”

So began Tatiana’s brush with homelessness.

She floated from friend to friend, her parents refusing to let her back home unless she obeyed their stringent house rules. That included prioritizing school over socializing. Tatiana felt smothered. She refused to comply and found herself briefly sleeping under the stars in a tent that rustled in the cold wind.

Laurie anxiously answered unknown numbers on her phone, hoping it was her daughter. She was shocked to learn that her “Love Bug” was walking among felons, possibly sex offenders and convicted murderers.

On some days that they connected on the phone, Tatiana cried. Laurie held back her own tears as she comforted her. On other days, Tatiana consoled her mother, insisting that she was doing OK.

Tatiana was not ready to go back home and live under her parents’ thumb. She preferred her freedom.

She alternated her nights between the dorms of Gainesville’s largest homeless shelter, GRACE Marketplace and the tents of the Dignity Village encampment just outside of the shelter’s compound.

At 19, Tatiana had to learn how to fend for herself for the first time. She quickly observed the rules of the streets: don’t ask for people’s real names and not everyone is a friend.

“Once I moved out, it was kind of a rite of passage,” she says. “But it was really scary — I saw a lot of violence; how another human can hurt someone.”

Tatiana stood out amid the other homeless residents. Her rounded cheeks gave away her youth. She was talkative and liked to crack jokes. In time, she developed a tougher shell. She began to walk with authority, head held high. She memorized the layout of the tent city – where the safest place was to hang out and who to stay away from. Her confidence on the streets grew.

She experimented with drugs. After taking a drag from what she believed to be pot, Tatiana’s head drooped as she came in and out of consciousness.

Later she suspected that her marijuana was laced with a stronger, more dangerous street drug. She witnessed a man overdose on spice, a cheap synthetic marijuana popular among homeless drug users. The man’s body went limp, all sign of life escaping him. Tatiana trembled at the sight, and a bystander had to pull her away from the horror. She vowed to never to accept drugs from a stranger again.

“I was very sheltered growing up,” Tatiana says, “I was a silver spoon baby.”

When she was 8, Tatiana asked for a rainbow-theme room. Her parents painted it pink, purple and sky blue. The bedroom remains exactly how she left it.

As a nurse, Laurie always chose to work the night shift so she could be home with her daughter during the day. Tatiana tagged along on her mom’s errands. Laurie sat down to do homework with Tatiana. They did everything together.

“I just miss hanging out with her. Her presence,” Laurie says. “She always liked being around people.”

That’s why it was even harder for Laurie to accept Tatiana’s misfortunes.

That’s why she was unimaginably relieved to learn one day that Tatiana was on her way to upstate New York.

Tatiana had managed to connect through Instagram with her uncle, who agreed to take her in at his home in New York. She took advantage of an opportunity that GRACE offers to its residents – a one-way Greyhound bus ticket for $160 and an Uber ride from the shelter to the station.

Once again, Tatiana packed her belongings, though she didn’t carry much. With the clothes on her back, one little bag and a heart full of trepidation, she climbed onto the bus.

“I wanted to help everybody else and save them,” Tatiana says, thinking about all the people she met during her tumultuous week in a homeless encampment.

She felt tears well in her eyes. She knew this was her chance to escape; that few were afforded this opportunity. Laurie had desperately wanted Tatiana to return home to South Florida. But at least her daughter had escaped homelessness.

As Tatiana made her way up the East Coast, she could only think about the distance she was putting between herself and life as she knew it — her parents, her dog Maxie and the warmth of Florida. Yes, she was scared. But she was ready for a new life. One, she hoped, that would be better.

MARK

Bicycle Man rides as fast as the wind, escapes homelessness on two wheels

By Edysmar Diaz-Cruz

In a strange way, homelessness can sometimes feel like a break from civilization, an extended vacation of sorts that makes bills and responsibilities a distant memory. It has been this way for Mark Sheldon for so long now that thinking about the real world is overwhelming.

Mark, 62, admits he’s grown complacent and somewhat lazy in his homeless years, though he does keep busy fixing bicycles at his shop in Dignity Village. He’s come to be known as “The Bicycle Man.” It amuses him. He wears the title with pride.

A welder by trade, Mark accumulated bike parts over the years and opened a shop where he does repairs. He owns 41 bikes that are ready to be sold or exchanged. He doesn’t charge much — no more than $20 — and paints the expensive ones in camouflage so they don’t catch the eye of late-night looters.

He got his first bike when he was 5 and finds joy in knowing that he plays a significant role in helping others obtain reliable transportation.

“It’s powered by you,” he says, “You go as fast as the wind. It’s freedom.”

Mark’s skin is tan and leathered from pedaling long afternoons in the sun.

Wafts of gray hair sit on his head, and the wrinkles on his forehead glisten with sweat.

Tattoos of faded skulls and chains wrap around both of his arms all the way down to his calloused hands, usually smudged in grease.

Mark’s handmade shelter in Dignity Village is surrounded by scavenged bike parts. Rusted bike frames line up against a wooden fence. Each tells a story of its previous owner. One bike has

a rather large distance between the pedal and the seat, which means the rider must have had incredibly long legs. Mark suspects it may have once been used to race in the Olympics. This one is not for sale.

For some of Mark’s clients, bikes are the only way to get around Gainesville. The nearest gas station is a five-minute ride and Walmart is 30 minutes away.

Mark’s latest client, a slim 58-year-old man, whose blonde dreadlocks spill out of a red bicycle helmet, is on the search for a bike part. He arrived at the homeless shelter seeking help finding a job. Fixing his bike, he thought, could be a key first step. So, he went to see the Bicycle Man.

“I’m one step above homelessness,” he says, “I’m sleeping on an air mattress with a hole in it.”

On some days, Mark helps out a friend, William “Bill” Henderson, 54, who also runs a bike shop at his campsite in the woods. Mark has been teaching Bill the art of bike maintenance.

“He’s one hell of a fabricator,” Bill says. “He does the high-end stuff.”

On this day, Bill hopes to finish a bike he’s been building to impress a woman.

“She gets all nervous and jittery when she sees me,” he says with a gleaming smile.

For Bill, bike repairs are less about making money – he’d be lucky to make $1,000 in a year repairing the bikes of homeless folks – and more a way to pass the time. He enjoys his shop in the woods and the thought of moving into a house makes him feel claustrophobic.

“I’m not ready to get a job,” he says. “Not because I’m lazy, but because [I] can’t handle it. I don’t want to start paying bills again. Right here, I’m at peace.”

In the woods, he can hear the birds chirping. The rustling of the trees in the wind calms him. His two plump cats, Pumpkin and Buddy, love to explore.

Neither Mark nor Bill feel ready to take on the world’s madness again. But that’s not to say Mark doesn’t long for the past. He thinks about the mobile home he shared with his wife before they separated. In September of 2017, he was forced to leave it behind when Hurricane Irma felled a tree that demolished it. He sought refuge at GRACE Marketplace and has remained there since.

“I miss my TV, getting up from bed, opening my refrigerator, making myself a sandwich and yelling at my neighbors,” Mark says. “I’ve been using a porta-potty for two years.”

To escape what feels like confinement sometimes, Mark daydreams about traveling. He relishes the rush of adrenaline, whether it’s from peering over the Grand Canyon, bungee jumping from the Eiffel Tower or going scuba diving in crystal blue waters.

But, above all, Mark thinks seriously about opening a legitimate bike shop with Bill, one which will give him a real income. And if he saves enough money, he’ll blow it all on a Harley Davidson.

TYGUR

The self-proclaimed mayor of Dignity Village laments its loss

By Edysmar Diaz-Cruz

James Scott believes lost tribes find one another in Dignity Village.

He propped a tent at the entrance to this encampment outside Gainesville’s largest homeless shelter so he could welcome all who wander in. And, he keeps an extra tent handy, just in case a newcomer needs one. It’s a gesture that has helped Scott, known as Tygur, proclaim himself the mayor of Dignity Village.

People come and go, but Tygur’s goal remains the same: Extend a helping hand to those experiencing a rough patch in their lives.

Recently, Tygur patched up a crack in the window in one of the shelter’s dorms. An elderly woman prone to pneumonia was sleeping by the window and feared the cold air that seeped in at night. So Tygur returned with duct tape and scraps of trash bags.

His right hand shimmers with chunky silver rings. Sometimes, he struts in a cream-colored suit topped with a straw hat. A faded tattoo of a tiger kisses his left cheek.

“It’s a powerful beast,” he says, “The animal could rip your head off, yet it is gentle with its cubs. A tiger is a protector.”

Dignity Village residents stop to greet Tygur. Many of them are young men who fell through the cracks of society, fell into trouble. They call Tygur “Big Dawg” and Tygur acts the role as a godfather to lost souls who need mentoring.

Tygur spends a good chunk of his time guiding young people who are homeless. He calls his program RISE: Respect, Integrity, Security, Empowerment. He gathers his people every Friday afternoon at 4 so that they can air their struggles and offer one another support. Sometimes, Tygur barbecues over a campfire near his tent.

He has been living on the streets of Gainesville for as long as he can remember and only recalls remnants of his former life. He had ambitions once; even had a rapping career. He performed at downtown Gainesville joints where he sold CDs. One of his songs, “Gator Bait,” can still be streamed on Spotify and Youtube.

These days, he keeps a large black speaker inside his tent, out of sight from potential thieves. On lazy Sunday afternoons, he lounges away from the heat of the sun and listens to Motown classics like Otis Redding’s “The Dock of the Bay.” Even the security guards at Dignity Village can’t help but sing along.

Tygur can no longer say with any certainty how long he’s lived without a real home. He drifted from his mother’s house once he began volunteering at St. Francis, a local homeless shelter. Eventually, he left altogether.

“I got lost in helping people,” he says.

In 2014, he helped homeless veterans in an encampment near the Depot Park trail. When it was suggested that they move to GRACE, they looked to Tygur for guidance. If he went, they would, too.

“When you’re homeless, you have to get to work. You need to build shelter,” Tygur says. “I’m a caring, nurturing person. I have skills for survival and I share my knowledge.”

Dignity Village residents credit him for founding the encampment. And over the years he’s played many roles — an advocate for the homeless, a peacemaker and a guide. He’s particularly proud of his work as a visual artist – he has an affinity for hieroglyphics and religious symbolism. Sketches of pyramids and the all-seeing eye embellish most, if not all his belongings at Dignity Village.

As the city and county began closing down Dignity Village, Tygur felt nostalgic about the micro-city he helped build. He remembers a time when there were only 25 tents; Then, there were too many to keep track. Then there was disorder.

“It could have been good for the community with more upkeep,” says Tygur, who had led various volunteer efforts to keep the tent city clean and organized.

But as residents begin dispersing into different parts of Gainesville, they leave behind personal belongings: paintings, wooden furniture, pots and pans. A heap of trash stands in the place of where tents used to be. Tygur surveys all that is left and laments the end of Dignity Village.

“This place is going away,” he says, “We built a community. It’s kind of a family.”

Tygur has no problem with building another camp like it. As his deadline to move out approached, he rode a bike around Gainesville and scouted for a new place to live. His search led him to a parking lot behind a secluded appliance store.

The lot had an ample amount of space under a cool shade of trees near a dumpster. Tygur spoke with the business owner who agreed to let him stay on their property. He knows better than to share this information right away. But if someone needed the help, he’d take them under his wing.

A mosaic of sunlight seeps through his straw hat as he labors through one Saturday afternoon. After two months of selling his artwork and doing odd jobs, Tygur saved $200 and purchased a motor for his three-wheel bicycle. He plans to use it to transport a sturdy wooden box. He calls it “the Camper” and soon it could become his new shelter in another place. Just a box next to a dumpster.

RUPERT

A flag for a friend who sacrificed for his country

By Chris Day

Rupert Heard’s name is rather appropriate. That is, most people can hear him before they see him. His laugh, thundering and infectious, echoes through Dignity Village.

Rupert, 57, occupies a tent atop a small hill. He doesn’t have many possessions but cherishes an American flag in safekeeping in his tent. It brings back memories.

Until about a year ago, Rupert shared the hill with Michael Burnette, whose tent was pitched just a few yards away.

Michael fought in Vietnam. Rupert describes him as a war hero, telling stories of dangerous rescues and low drops out of helicopters with no parachute — “hero stuff.” People in the camp called him “The Bear,” though by the time Rupert met him, he was ailing and wheelchair-bound.

But Michael had his monthly veteran’s benefit check of $1,074 — a lot of money in a homeless encampment.

Rupert befriended Michael after seeing him smoke cigarette butts he found on the ground. This bothered Heard, who believed a veteran deserved, at the very least, new cigarettes. And there was no reason with his benefit check that Michael shouldn’t be able to afford them.

Rupert discovered that Michael had been trusting his checks to others in the camp to manage for him and make grocery runs. But they were taking advantage of Michael, wasting the money on liquor. It always ran out early in the month.

Rupert put a stop to all that by taking over Michael’s finances.

“No man that gave his all for his country should have to live like that,” Rupert says. “I saw to it that didn’t happen anymore.”

Rupert budgeted the check to make sure it lasted the month, bought food and fresh tobacco for the veteran. He took clippers to Michael’s hair and beard, joking that he looked like Santa Clause. A tight friendship grew.

Rupert would cook for them and make his famous “cowboy coffee” over the campfire or grill. “Here’s to Gainesville and the rest of the world,” they would say every morning, raising their coffees in a toast.

Michael was placed for a time in a one-bedroom apartment but told Heard he didn’t like it. He was lonely, watching TV or listening to the radio all day.

“How much of that can you take?” he asked Rupert.

Michael eventually returned to Dignity Village, where people knew his name and he could pass the time with real conversations. Where he could share a cup of coffee with Rupert.

Then, one day last year, Rupert was inside one of the dorms on the GRACE Marketplace campus when someone said, “Rupert, you gotta come out to your camp.”

Rupert took down an American flag from a flagpole on the hill and draped it over Michael’s body. The coroner later covered Michael with a new flag, and returned the old one to Rupert. He’s kept it safe in his tent ever since. He holds the flag gently in his hand and brushes away dust as he remembers his friend.

“That flag can never touch the ground,” Rupert says, his throat catching and his eyes pooling with tears. “That was a dear friend of mine.”

Rupert gave away all his tobacco two months after Michael died. He couldn’t do it anymore. The cigarettes he rolled reminded him too much of his friend.

Now, it’s just Rupert. Still going strong, if not a bit lonelier.

“Cheers to you Mike,” he says, and lifts his cup and eyes to the sky.

Explore more chapters

Special Report from WUFT News

Special Report from WUFT News