By Gabrielle B. Calise | April 25, 2017

Florida immigrants speak out on family, faith and the “American Dream.”

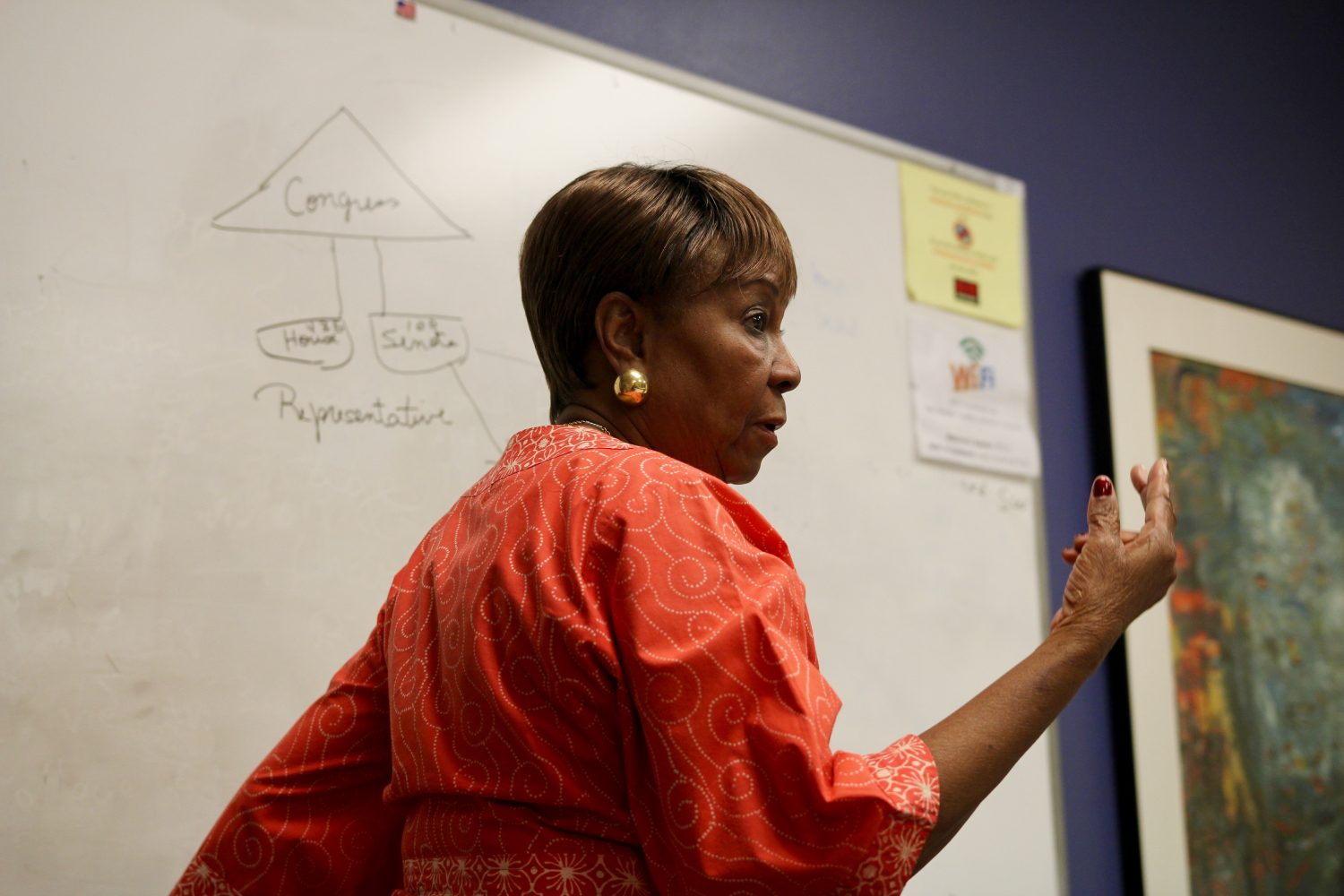

It’s Thursday morning in a classroom at the Marion County Literacy Council — time for another citizenship test prep class. Six women make their way in, spiral notebooks and purses in hand.

The Marion County Literacy Council hosts English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) classes, and often the students in these courses want to become citizens, too. The council’s weekly citizenship prep classes help students learn about the U.S., improve English skills and gain confidence.

For the next two hours, the women will sit through American history bootcamp, covering everything from Congress and the Constitution to the number of stars on the flag.

Joycelyn Phillips, a tutor from the Virgin Islands, drills her students without giving them a break. She is kind but strict, and it works. In her seven years of voluntarily teaching the class, Phillips has never had a student fail the test.

For her students and other immigrants, this test means a lot. It means having the right to vote. It means having new opportunities, rights and responsibilities that come with American citizenship.

Immigration isn’t a topic that will fade away anytime soon. Twenty percent of people in Florida are immigrants, according to the Migration Policy Institute. With different changes to immigration policies being proposed, discussing immigration can sometimes be controversial.

But trying to understand the stories of immigrants is crucial, said Richard MacMaster, coordinator of Gainesville Interfaith Alliance for Immigrant Justice.

“I understand if I know what you are coming from and who you are, and that’s a very important step to take,” said MacMaster, who is also the chair of the board of directors of Welcoming Gainesville and Alachua County. “We can have all these horrible anti-immigrant regulations as long as people think, ‘Oh yeah they are all murderers, rapists, drug dealers, terrible people. We don’t want them in our country.’ And then you turn around and say ‘Wait a minute. The surgeon that saved my baby’s life is an immigrant and he’s from a Muslim country.’”

Welcoming Gainesville and Alachua County is in the process of gathering stories from immigrants to share with the public, MacMaster said.

“It’s very important if you don’t actually personally know people to get ways so that you understand them, who they are, why they’re here and what propels people to come,” he said. “Obviously they have all different reasons.”

WUFT spoke with Floridians who have immigrated here and those who helped and supported them along the way. From students, undocumented immigrants, refugees and allies, these are their stories in their own words:

Jacob Atem

Jacob Atem will tell you that he was supposed to die many, many times over. But for some reason, he lived.

Atem is a Lost Boy, one of the 20,000 Sudanese orphans who were displaced during the Second Sudanese Civil War. When Atem was six years old, his parents and several siblings were killed. He fled from his burning village, leaving behind everything he had known, and walked 1,000 miles to Ethiopia with his cousin, Michael.

After spending years in refugee camps, Atem was one of about 4,000 Lost Boys who resettled in the United States. He co-founded the Southern Sudan Health Care Organization and is currently pursuing a Ph.D. at the University of Florida.

“All my life I grew up as a refugee. I was given the opportunity to come to the land of the great, the land of freedom, to come to America. You know, we the Lost Boys used to call America ‘Second Heaven.’ It’s because you have that opportunity. At that time, I barely spoke English. At that time, my focus was not education. My focus was, ‘Do I have a hot meal to eat, where [will] I spend two to three more days without eating?’

Now, fast forward. When I came in 2001 in April, I was what they call underage. I was in a foster care. I was given to be there for three years. I was thrown into a high school, where I barely speak English and I was learning about Shakespeare.

If you were to ask me today what would happen to me; first of all, I would never get educated. Second of all, I would never dream to have a nonprofit. I would never have thought about graduating from a small Christian college with my first degree, biology, when my family was never into the education component. I would have never thought that I would go to a big institution called Michigan State University and graduate with a degree in public health. I never thought I would be a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Florida, and I’m trying to get this organization, Southern Sudan Healthcare Organization, to the next level.

I’m saying all of this, because it really broke my heart. Because the way we — I say ‘we,’ I mean the Americans — are portraying the immigrants and the refugees as if they are the problem. As if they are the core issues. As if they are all bad.

I lived on many occasions in several refugee camps. Literally, it is open prison. Literally, it is where you cannot find hope. Literally, it is a place where you just wait for your grave.

I think we tend to forget that nobody owns America. It just hurts my feelings because when my friends, who I met in the last 16 years, had been in this country, they don’t understand the refugee crisis. As we speak, we have 65.3 million forcefully displaced across the world. Out of those 65 million, estimated either 20 [million] or 21 million are refugees, and actually most of them are women, children and elderly. And actually most of them resided in southern Sub-Saharan Africa.

What do you make out of people who are lucky, like me? How many refugees have made it here? How many immigrants have come here? And how many are doing good? Just take the Lost Boys as an example. Most of them give back — have clinics, open school, some of them work for the government.

One of them, like my cousin, have three tours of duty to Iraq. Most of my Lost Boys are in the army. That’s what makes America great.

Freedom we enjoy here is a luxury. The fact that we just had a nasty campaign, toxic, and we don’t have a civil war — it is a joyful moment for me. In other countries, it is a bullet. It is innocent women and children who are dying. Political disagreement between the politicians is political assassination. It is killing. But that is not the case [in America]. We can bicker all we want on social media and all of this, but at the end of the day, [we have] this big blanket called The American Dream. I am more grateful for America because I have seen it all.”

Victor Constantin and Ali Jamoos

Ali Jamoos, a UF international student from Palestine, had just two semesters left until graduation when he went on medical leave to take care of his sick father.

Upon his March 10 return from a Spring Break cruise, Jamoos was detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement in Port Miami. He now faces the threat of deportation.

After watching his friend be taken away at the port, UF alumnus Victor Constantin launched a GoFundMe page to raise money to hire a lawyer. Here, he shares the story of how a community of strangers reached out to help his friend and what might happen next:

“It was horrible to see him being taken away in handcuffs. With everything going on, we were already always worried about leaving the country, but since a cruise is what they call ‘a closed circuit’ kind of thing, we figured it wouldn’t be such a big deal. Immigration to the U.S. is always a scary and intimidating thing because it’s just such an unpredictable event. He’s from a country where it’s already not very easy to immigrate from the U.S.

It was him and another Palestinian friend that they pulled aside. The other Palestinian friend came out after two hours, and he didn’t — and that’s when I really started to get worried. And then 10 minutes after they released the other friend, they released Ali in handcuffs and drove him to the main immigration office.

I have spoken to him on the phone and our friend from Miami, she’s gone to visit him. But the first couple of days, since it was a Friday when he got detained, they wouldn’t tell us anything. I mean, we called so many different places. We called lawyers, we called the ACLU, we called different officers, and just nobody could tell us anything — where he is, how he’s doing, what’s happening to him. And then, only on Tuesday, is when we found out finally that he was being detained at KROME, but that they were transferring him to the Broward Detention Center.

He’s doing much better now. They were treating him really badly. They were just really mean to him throughout the whole investigation. And then at KROME, which is like a detention center not just for immigration, but for criminals, he said that was like a legit prison, with people all tatted up and really people all over the board. But the Broward Detention center is much better. They have a lot more freedoms and he’s made a couple of friends there already. But obviously, he’s still there in an orange jumpsuit. It’s still prison. It’s just a little bit better.

We spoke to a couple of lawyers. The lawyers all said that they need between $3,500 and $4,000 for his case, and they won’t start work without having that money. It was especially important that they start to work as soon as possible because they were starting his deportation process, and if he gets an involuntary deportation, he can’t come back for the next five years to the U.S., which would mean he can’t finish school.

He got a full scholarship for UF, and that would just be horrible if he can’t finish the last two semesters because of a tiny medical withdrawal thing that was still processing. It was just really bad, and we knew we had to help him and get a lawyer for him and make everything possible so that that wouldn’t happen with the mandatory deportation, so that he would have a chance to finish school.

The most important thing is just seeing how willing people are to help and how powerful the network of people all around the world is.

[Response to the campaign] was overwhelming. I think we had our goal met within less than three hours of creating the campaign. And people are messaging us so many encouraging things. So many people are donating and sharing — I think over 1,500 people have shared the post and there are 250 people that have donated money (266 people raised $8,835 in 17 days), most of whom I’ve never even heard of their name. It’s been really, really amazing.

It’s just incredible what the power of people can do. These 250 donations, I’m sure they’re from at least 50 to 80 countries, so it’s really help from all over the world.

We initially had one lawyer, and we are now just trying to find the best lawyer to represent him. We’re talking to a couple of different ones and see who we think is the best representation for him. We’ve already discovered that probably the $3,500 initially that we thought it was going to be is not the only cost that he is going to have to pay, so it’s actually really amazing that people already donated more than the initial goal of the campaign because we’re pretty sure that he will need it after talking to several lawyers now.

The medical withdrawal has come through and he’s been reinstated as a student already, and so that made his case a lot better. We’re hopeful that he won’t get the involuntary deportation, so either we can get him out of the detention center and he can go back to school, or he’ll get the voluntary deportation, but then he would be able to at least re-apply for a visa and come back to the U.S. for school.

This is a life-changing thing if he can’t finish school or if he is able to finish school. That makes a big impact on his life. The most important thing is just seeing how willing people are to help and how powerful the network of people all around the world is. How quickly that can spread and even if people make small donations, how big of a difference it can make, and how quickly [it can] make such a big difference.”

Grey Torrico, J.D.

As an undocumented college student, Grey Torrico didn’t know where to turn for support. She channeled her frustration into founding CHISPAS, a student organization that advocates for immigrant rights through awareness and education.

Since graduating from UF in 2009, Torrico has continued to fight for immigrant rights, as well as earn a law degree. But no matter how busy she is, Torrico remains invested in CHISPAS, which still helps immigrants both on and off campus to this day.

“I was born in Chile and I migrated when I was seven. I think the idea of displacement is something that has played a huge part in my analysis of growing up. I’m bicultural and it’s something to be said around the way that we’ve been displaced from our communities and kind of been put into — not by choice, but almost by nec

essity — been kind of drop-kicked into different communities. For many of us, it’s been this struggle of trying to find our own identity. My story is not unlike other folks in terms of what it looks like to access language and services and economic stability that many people seek. I definitely think that right now we are in a moment where we’re going to see so much change in the way immigrants are being treated.

I was undocumented at the time that I went to UF, and during my junior year, I really felt impacted by a lot of the federal legislation that was taking place at the time. The DREAM Act, which would have given undocumented youth at the time a pathway to citizenship, was still in play. I felt really connected to the issue for obvious reasons and kind of really impotent, angry — there’s a lot of different feelings I was feeling at the time — and decided to channel it on campus to find a way to really garner and cultivate an atmosphere that I felt good and safe in. At the time I didn’t know anybody who was like me and undocumented, and from there it kind of just snowballed.

It was a period of time that there was definitely a desire to continue working on immigration at a national level and kind it trickled down to our campus life.

At the time, I didn’t know how much logistics really were needed for all of it, but the biggest thing that drove me was the desire to connect with people like myself. At the time, I had been really involved with the Hispanic Student Association, all of the different Latin organizations on campus, and I figured that was a really good way to connect. I started connecting with a lot more folks after the founding of CHISPAS. I think that people really, really were receptive. Again, this was around 2008, 2009 and this was a year after the DREAM act had came up for a vote and then in 2010. It was a period of time that there was definitely a desire to continue working on immigration at a national level and kind it trickled down to our campus life.

I found out I was undocumented when I was 16 and so it didn’t really hit me until later in life when I was in college.

UF was a really great place for many reasons, but it was really hard to talk about my status. It’s not like now, where CHISPAS has done an amazing job really talking about this issue. Way back then it wasn’t the case. It was a lot harder to have a conversation on campus about it. People didn’t understand, and I think that it was really lonely.

I think CHISPAS really provided a safe haven for not just myself, but for other people who felt the desire to connect as well.

I began with a very idealistic idea around really wanting to connect folks to the immigrant community, on campus as well as off, and really wanting to do more direct services-impacted programs. We did a lot of English classes for the immigrant community locally and things like that … but over time, it’s evolved into this idea of really wanting to engage people and their political power. It’s really become this really great grassroots, social justice-oriented, direct-action type of group. Now they do a lot of work around farm worker issues, so they brought the Coalition of Immokalee Workers.

After I graduated, I did a lot of social justice work. The six years after I graduated I ended up doing community organizing with the Florida Immigrant Coalition and I did a lot of immigrant rights work based around enforcement programs — so you know, a lot of the ways people get caught up in the deportation dragnet in our communities. And after that, I went to law school. I recently graduated from law school and took the bar in February. I figured that after doing a lot of organizing work, I wanted to connect on the legal end.

As a legal permanent resident, you’re still at the risk of being deported. That’s one of the reasons for me why (getting citizenship) was important. And the other reason was becoming a citizen allows you to have the ability to support your family and you can claim them. My family had come with me when I first came to the U.S. and (becoming a citizen) gave me the ability to make sure that they were safe, they were protected and that they could remain in the United States. Honestly it was really a strategic decision for me.

Becoming a citizen does require that you have at least some connection, be it a spouse or a family member who is a legal permanent resident or a citizen, who can petition for you so that you can go through the process. At the time I was married and my spouse petitioned for me. It’s very important for folks to know that to become a citizen, there’s a lot of different things that go into it.

People just don’t understand what it is to go through that whole process. It’s a lot harder than it seems at first glance, and for me it took years, not to mention a hefty sum of money, to get through litigations, between legal fees and immigration costs and things like that. It’s a huge privilege to be able to say that i went through the process. Not a lot of people can afford a citizenship application, which at this point is around $600, and that does not include any previous applications that you’ve done — you know, spousal applications and things like that. It’s a huge privilege that i was able to go through that process, both legally and financially.”

Matthew “Trevian” Baquero

Over a hip-hop beat, Matthew Baquero describes the scene: a young man watching his parents being dragged out of their bedroom by immigration enforcement officers.

Rapping under the persona “Trevian,” Baquero, a 22-year-old UF telecommunications senior, has a goal of bringing awareness about immigration issues.

The project started when Baquero received his final assignment for his electronic field production class. Baquero decided to write a song and shoot a music video about immigration.

“I’ve made music videos before that have had socially conscious issues brought up, whether it’s alcoholism, domestic abuse, suicide. I wanted to do another one because I hadn’t done one in a few years. I wanted to do something that’s really relevant, and obviously this is really big in the news and America as a whole.

I saw this interview that Diane Guerrero (an actress from shows Orange is the New Black and Jane the Virgin) did on CNN and she talked about her struggles with immigration herself, how her parents were deported back to Colombia and her struggle of having to grow up pretty much on her own since she was 14 years old. That really hit home for me when I saw that.

I want to make more songs that are upbeat as well, that aren’t as depressing, but I definitely love making this kind of music because it addresses the important things that are going on. I have family members that are in a similar situation that are living in the States right now, and, I mean, they were born in Colombia and they came here at a really young age, so this is all that they know, the United States. I can only imagine those family members going back to Colombia and they’ve never been there before. This is the country that they know, they are American. The only difference between them and everybody else in this country is the place where they were born.

[This music] is coming from this place inside of you that just has so much rage, so much passion and you just want to share this with everybody.

I saw this article on CNN about a 22-year-old kid who got deported to Mexico. He was born there, but he came here before, and he barely knows how to speak Spanish. I just fear that, God forbid, something like this would happen to one of my family members. Growing up in a Hispanic-American community you know a lot of people that are facing this struggle, and I feel like as a Hispanic, as a Latino, it’s definitely more prevalent in other communities within the country.

I feel like these kinds of songs, they’re easier to write because everything’s coming out naturally. It’s coming from this place inside of you that just has so much rage, so much passion and you just want to share this with everybody. And the recording process is very easy too, because you just get into it. I’m narrating the first verse, the second verse I’m obviously rapping it too, but I’m still telling it from the perspective of the main character. And so, I kind of just get into what he’s probably feeling.

I want people that don’t know what the hell is going on or have never experienced anything regarding immigration to open up their eyes and see that the world isn’t just what’s in your bubble. There’s so much going on, there’s so many people suffering. So many people. There’s this lyric in the song that goes ‘You don’t understand/ the stakes that are at hand/ the risks that people take to become legal in this land.’

I just want people to be more open to other people’s opinions. Stop being closed in a bubble because the whole world isn’t going on inside of yours. I just want people to accept people of other backgrounds. I feel like the whole world could be a better place if we could just see the world from the perspective of other people’s eyes.”

Sunny Saini

Sunny Saini’s family moved to Melbourne, Florida, from India when he was two years old. Now 22, Saini is a UF geology student with the dream of earning a Ph.D. He tells the story of coming to America as a child and continuing to celebrate his Indian roots.

“I was born in India in a state called Rajasthan in the city of Jodhpur in 1994. I came to America when I was two-years-old. My father got a work visa to come work for VRI here in Florida. We came over and I spent around maybe half my childhood in India up until I was six or seven years old.

I remember flying on airplanes… it was really a cool experience for me as a kid. I remember living in our old apartment. It was really small. My family wasn’t too well off when we arrived here. We lived in a one-bedroom apartment and I remember just watching television sometimes and spending the days like that. There was a bit of a language barrier, but I picked up English pretty well and I had adjusted by the time I started school.

There’s my mother, who works at home. She mostly stays at home, and then my father — he’s a software engineer currently working at GE. And I have a little brother who was born in America when I was five-years-old, so he’s currently 17.

All of my extended family is in India and they had a huge influence on me — all my grandparents, my cousins, my aunts and uncles, are all in India. Whenever I used to visit them I would spend half my time in Jodhpur, which is where my nana and nani (which is my maternal grandparents) were and I would spend half my time with my dada and dadi (my paternal grandparents) in Sikar. They influenced my life quite a bit. I learned a lot of Hindi from them. I was born in a city that’s famous for its rock mining, and I think that has influenced me to become a geologist in a big way. A lot of cool things happened in India that really shaped me.

In India, the quality of living isn’t extremely high and my parents thought they could lead a better life for ourselves in America.

I think my most vivid memory honestly is when I was on the airplane itself — there were a lot of different people and a lot of different, new skin colors and new faces and things like that. Before that, all I’d known were Indians.

In India, the quality of living isn’t extremely high and my parents thought they could lead a better life for ourselves in America. Engineers are still paid quite a bit above average in India, but the opportunities for him here are just better in America. My mom still misses her home and my dad still misses his parents, but we visit every few years, and we really just love it here. I’m not completely sure if my parents planned on our stay being permanent, but we’re citizens now.

My parents, or at least my mother, is very religious. We’re all Hindus. I’m personally not super religious, but we still hold a lot of practices like prayers, visiting temples, pilgrimages and stuff like that. A lot of the time when we go to traditional Indian events, we wear traditional Indian clothes. My mom will wear a sari, and me and my brother and my dad will wear kurtas, which are male garb.

I think that what people don’t really realize is, when you think of different people, you think they are a different breed of people almost. You think these are alien folks and they think different from us, and I don’t think that’s true. I personally know immigrants, not just from India, but from all over the world, and I think we are all very similar in what drives us and what makes us human.”

MacMaster remembers a revelation he had while visiting a hospital in Snellville, Georgia.

“I was just struck by the fact that if you removed all the immigrants who were there who were passing by – doctors, nurses, cleaning people, everybody — who clearly were not just native Georgians, this enormous, big hospital will have to close,” he said. “And that’s actually true in Gainesville. So many professionals came here… from all sorts of countries all over the world.”

From the medical treatment we receive to the food we eat, immigrants have a huge impact in our daily lives, MacMaster said.

“You have agriculture that depends really entirely on immigrants and you have job creators that are bringing businesses,” he said.

MacMaster hopes to encourage others to be more approachable to immigrants — partially to knock out stereotypes, and partially just to make the city a better place for everyone.

“If you get to know your neighbors and you really are a welcoming and inclusive community, you will get to learn a great deal from them, and they from you,” he said.

Working with immigrants at the citizenship classes has been one of the most meaningful parts of Joycelyn Phillips’ retirement.

“For me, it’s the number of lives that I have touched and the stories I hear about moving here, whether it be [from] Colombia or Venezuela or Mexico,” she said. “…What I have realized is in helping a parent become a citizen it helps the child, and the child helps the child and so on and so on. And that is the most rewarding for me.”

Phillips, who was born in the U.S. Virgin Islands, has not had to take the citizenship test. But the past seven years of teaching the class have taught her many things about the struggles and dreams of immigrants.

“I think for most of them, the American Dream is being self-supporting. Not depending on anybody,” she said. “In other words, being able to earn his or her own dollar and being able to decide exactly what he or she wants….There are many obstacles, but trying to overcome the obstacles, that’s the American Dream.”

Phillips recommends sitting in on a citizenship test prep class to experience what becoming an American means to immigrants. Even when her students struggle, their determination is inspiring, she said.

“Once you have that dream it’s almost impossible to be deterred,” she said. “I cannot see America as anything but better because of immigrants.”

Special Report from WUFT News

Special Report from WUFT News