A hurricane’s unseen effects on children

Jonathan Yates was a star student and on a scholarship for ROTC. But in the weeks and months after Hurricane Michael devastated the Florida Panhandle, the 14-year-old changed. He began talking back to his teachers, not finishing assignments and lying that he lost his school uniform. His mother, Nicole Dawson, even came across a troubling text to his girlfriend sent from his cell phone in which Jonathan bragged about taking a needle from his grandmother’s sewing kit and pricking his wrist.

“It scared the life out of me,” Nichole says. “This is not my son. I know my son, and he would never do anything like this. He has too much to lose and he knows that.”

Jonathan brushed his behavior off as a rebellious phase. But his parents know better. He was suffering from post traumatic stress. And he is not alone.

Something as traumatic as a Category 5 hurricane can turn the lives of children upside down. The chaos and the fear of a storm leave many families struggling not just with physically getting their lives restarted but with mental anguish. And that can be acute in children.

A study after Hurricane Katrina found that more than half of the children — in fourth through eighth grade surveyed in impacted areas of Louisiana — showed symptoms of PTSD, according to a study in the Journal of Traumatic Stress. Of those, more than 70 percent had seen something as traumatic as a dead body. Less than a third were separated from their family. Kids who weren’t trapped in their homes were evacuated by boat, helicopter or swam through stormwater to escape.

In communities littered with debris from homes and schools, it is common for kids to fall behind in class, feel scared or become stressed. The post-storm stress may even cause some kids to think about hurting themselves. A year after Katrina, the proportion of survey respondents who said they had suicidal thoughts doubled in the states affected by the storm, according to a study published in Molecular Psychiatry.

Now, young survivors of Michael are experiencing similar mental stress. Like Jonathan.

When Nichole saw the text, she instantly knew she wanted to move. She thought her son’s mental health might be salvaged if they could escape the constant reminders of destruction.

Suicide rates and children’s mental health are major concerns for emergency management officials after hurricanes, former Federal Emergency Management Agency Director Craig Fugate says.

“We see a lot of behaviors change, and the ones that are most concerning are the ones that tend to be abusive,” he says. “This is everything from increased drug use, alcohol use, cutting.”

In Jonathan’s case, Nichole says she reached out to his psychologist for help but still hasn’t heard back five months later. The center he used to go to for help lost its roof in the storm.

Studies show that children who are already experiencing mental health issues can be more adversely affected by anxiety.

Panama City psychologist Dr. Royce Gray had patients in his care when the storm hit. Some have needed more help after the storm, he says.

“It tends to be the case that what I’m seeing is that people who already had mental health problems before the storm, the storm exacerbated it,” he says. “If they already had depression before, they’re likely to have worse depression, or depression plus some other new condition.”

On his last visit to the pediatrician, Jonathan says he told the doctor his parents didn’t tell him they love him enough. The pediatrician prescribed him antidepressants.

Jonathan has never experienced these types of feelings before, Nichole says. He’s usually happy. She says he’s her angel.

“He knew he was loved,” she says. “He knew he was bright, and he was confident, and now he’s not. I believe the storm took that away.”

Jonathan Yates shows off his awards with his mom, Nichole Dawson. Jonathan is in ROTC on scholarship and in the school’s band.

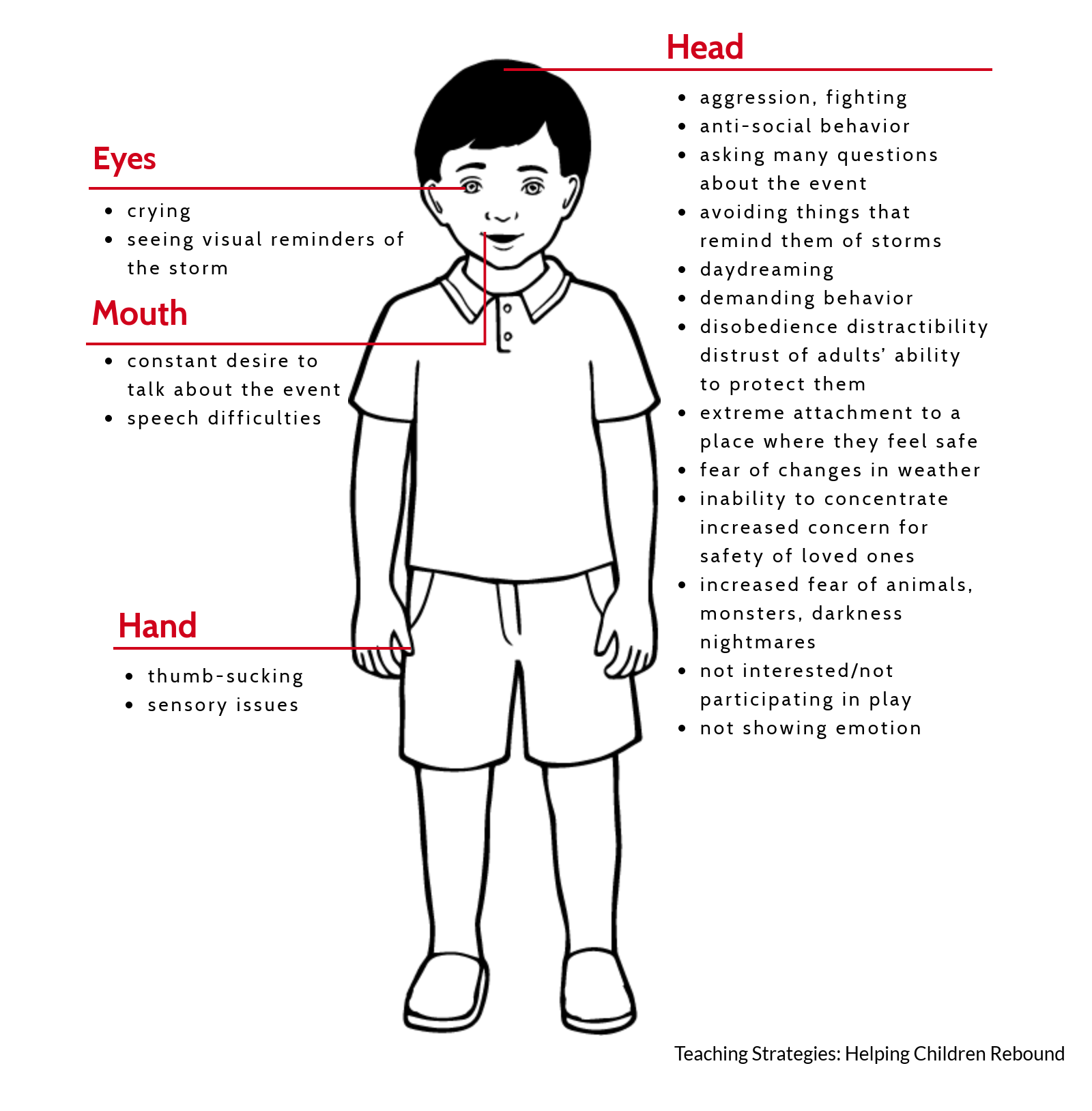

Children who live through stressful situations can develop what seems like irrational feelings, especially fears that come up out of the blue, says psychologist Dr. Elyssa Barbash, a PTSD and trauma specialist.

Kids may complain about physical symptoms, “such as headaches or tummy aches, that don’t really seem to have a true physical origin,” Barbash says.

For children facing anxiety-inducing events, trauma can manifest itself in different ways, Gray says.

“Their reality is a little different than adults,” Gray says.

Parents may have trouble relating to their children’s’ worries because they don’t react like adults, Gray says.

Marleena “Marlee” Dawson, 3, dressed up in a princess costume. Her mother Nichole Dawson says the girl dresses up more since the storm.

When Marlee, Nichole’s 3-year-old daughter, began wiping herself so much after using the bathroom that she developed a rash, Nichole didn’t know what to do.

Sensory issues are one common symptom of anxiety.

Marlee had other fears. She was afraid of cracks — anything from a crevice in a wall to a split in the vinyl of a doctor’s waiting room chair. She’d whimper, begging to get away.

“It’s hard to wrap my head around and understand,” Nichole says. “I know anxiety is different with children, but it’s so strange.”

Nichole took her baby girl to the pediatrician, who told her Marlee had anxiety and recommended finding a book to read but didn’t offer any suggested titles.

Nichole left the office feeling helpless. She didn’t know where to turn. She joined Facebook groups for parents of children with anxiety. She wrote instructions for her daughter in the bathroom.

Her frustration continued to build.

“I get upset; I yell,” she says. “I try my best to handle it,to stay calm, but there’s no answers.”

Despite the frustration, many parents are trying everything they can to help their children find comfort and sleep better at night.

Symptoms of stress in children

Special Report from WUFT News

Special Report from WUFT News