By Grace King | April 29, 2019

BATON ROUGE, LA. — When Marylee Orr’s son Michael was born, he was diagnosed with a respiratory disease.

She decided to take matters into her own hands.

“The air was unhealthy when he was born,” Marylee said. “Now he’s well and whole and I’m very, very grateful and try to pay that forward every day because he could have had some very serious health issues.”

For the last 30 years, she’s dedicated her life to the Louisiana Environmental Action Network, an organization for which she co-founded and now serves as the executive director.

“LEAN revolves around people and about their struggles, their health, preserving the natural resources in protecting their health,” Marylee said. “We just talk about the disproportionate impact to low-income minority communities.”

She said she believes the solutions lie in empowering those less fortunate rather than advocating on their behalf.

“We go in and help them find a voice all the way from their local community,“ she said. “If we don’t preserve their voices, they’re going to be lost.”

Marylee said she fears outside companies with deep pockets are constantly overpowering the voices of people living Louisiana.

Campaign finance data shows oil and gas industry companies were frequent donors to Democratic Gov. John Bel Edwards’ 2015 gubernatorial bid. In total, donation database Vote Smart estimates the industry contributed more than $138,000.

Edwards supported the Bayou Bridge Pipeline and industrial expansion, though he has begun to question their environmental impacts.

“It’s tough. This is a lot about power and money and people,” Marylee said. “The people are you. The people are us. The people are me… They’re people who want to have a future. They want to live.”

They’re people who want to have a future. They want to live.

She said hopes her work allows future generations of Louisianians to live with their families and breathe easier.

“Sometimes the definition of success in Louisiana is different than it would be in other places,” Marylee said. “It’s a very complicated space.”

‘If you don’t fight, you die’

Darryl Malek-Wiley remembers being intrigued by a Sierra Club meeting in Wilmington, North Carolina. So intrigued, in fact, that he decided to become a conservation leader and dedicate his life to fighting against environmental injustice.

That was in 1972.

He now lives in New Orleans to help marginalized communities get records from the Department of Environmental Quality, become informed about the issues affecting their health, craft press releases and form their own opinions.

“It’s to help them understand that they’re not a powerless community; they have power and they just need to figure out how to tap it and move forward,” Darryl said. “I try not to be their voice, but I try to be the one behind helping them get their voice.”

I try to be the one behind helping them get their voice.

He spent 10 years helping rebuild parts of the Lower Ninth Ward after Hurricane Katrina. He fought passionately against the construction of the Bayou Bridge Pipeline. Now, he spends a good portion of his time trying to save those living in Cancer Alley.

“We have these gigantic facilities and they’re emitting a whole range of different chemicals,” Darryl said. “If you don’t fight, you die.”

Darryl said he thinks giving a voice and knowledge to the marginalized communities will help them advocate and push for changes.

“I fight because it’s something in me that says you know I need to help folks,” he said. “It is all about is helping people understand what’s going on.”

‘We’ve got to change’

Retired Lt. Gen. Russel L. Honoré served in the United States Army for 37 years, 3 months and 3 days.

He commanded the military’s relief efforts in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, which he said was one of the largest deployments of U.S. military within the 48 contiguous states.

Today, he is still goes by General. But now, he leads his own army with a different goal. His group, the Green ARMY, works to advocate for environmental change in impacted areas of Louisiana.

In this role, he unites existing organizations — such as LEAN, Sierra Club, Bucket Brigade — to fight against injustice together.

“I got involved with the Green Army to try and use my voice, to use the skills I learned in the military, to try and analyze the problem, try to come up with a solution,” Honoré said.

He goes from community to

community, taking pictures of the environmental destruction and finding ways to help improve the quality of life for those living nearby.

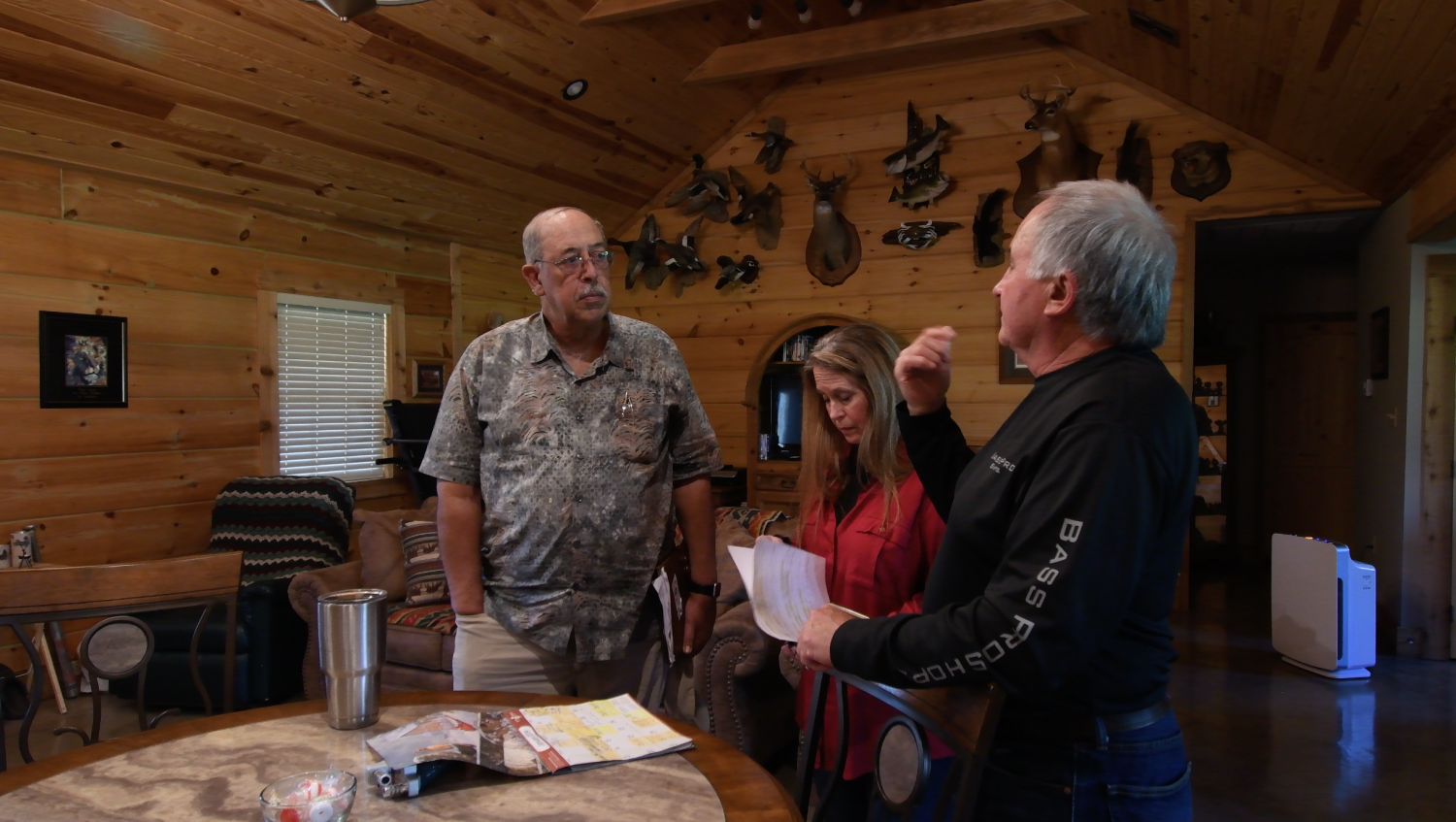

In the case of the LeBlancs, Honoré spent an hour listening to their symptoms, inspecting their air monitoring equipment and looking for ways to help. He said he will bring them a water testing kit and coordinate with Wilma Subra to make sure the state is receiving their data.

“If it was not for men like Russel Honoré and other people that will put their neck on the line for the good of the people, I’m sure it would be a lot worse,” Gene said. While the LeBlancs are still waiting for a resolution, they said they have hope.

Honoré is a prominent figure across Louisiana, and has used his status to help make a case for the marginalized communities. He said he and the Green ARMY helped lobby for eight bills in the Louisiana state house this legislative session, including one that could help the LeBlancs.

“People have a human right to clean water and clean air,” Honoré said. “It’s absolutely a crying shame to see how these companies are allowed to emit toxic air and toxic water.”

‘God will get us out of this’

In the heart of St. James Parish, sounds of hymns and prayer fill Mount Triumph Baptist Church every week. Pastor Harry Joseph preaches from his bible, just like he’s done for the past eight years.

As time went on, he noticed members of his congregation were starting to get sick with cancer and other life-threatening illnesses in an unusual way.

“It hurt because I’m a leader,” he said. “I just started speaking out because when my people hurt, I hurt and when they suffer, I suffer.”

He started attending city council and local government meetings to explain what was happening and ask for help, he said. However, that effort was useless.

“It’s a majority of black American, you know African American people and there’s a lot of suffering, so as a leader and as a pastor I felt that we need to be upfront in letting our government know how we feel,” Pastor Joseph said. “But our government don’t even hear us.”

Our government don’t even hear us.

Pastor Joseph said he does not believe the petrochemical industry will leave, so instead he is fighting for the industry to compensate his congregation members and allow them to move elsewhere.

“We just hoping that somebody just break something and start getting some people out of here,” he said. “This chemical stuff that we’re dealing with down here, it’s not good for our health. It’s not good for our bodies.”

Still, some families have lived in Cancer Alley for more than a century. Pastor Joseph said he fears leaving is not an option for everyone.

“They got their family here. They got their roots here,” he said. “Some people might not never want to leave.”

Pastor Joseph said he cannot leave if his congregation stays. However, he wants to see change in local leadership, new environmental policies and respect and compassion for each other.

“We destroy people for a dollar,” he said. “Money can’t buy you health and money can’t buy love and these are the things that we’re failing to do is to love one another and to help one another.”

Pastor Joseph said despite the adversity they’ve faced, faith keeps them strong.

“We got our leader and our help and we just continue maintaining our faith and trusting God,” he said. “I feel God will get us out of this.”

This journalism project was made possible by a fellowship from Marguerite Casey Foundation, which supports low-income families in strengthening their voice and mobilizing their communities to achieve a more just and equitable society for all. Meredith Sheldon contributed additional reporting and editing.

Special Report from WUFT News

Special Report from WUFT News