No Easy Street

By Monica Humphries | December 11, 2017

One family transitioned out of a shelter and into a home, but their struggles don’t end there.

Sandy jiggled the sticky lock, and they were in.

He opened the door to a two-bedroom apartment with dented hardwood floors and a cramped kitchen. Earlier Sandy, 43, and Millie, 27, exchanged a $25 deposit for a freshly pressed set of keys. The driver dropped off a queen-size mattress, bedframe, TV and foldable crib.

“We walked in, and it felt so empty,” Millie said.

“Hell, we unpacked everything, and it was still empty,” Sandy said.

After spending the past years in eight different homes and shelters, empty was good. So was silence.

Millie and Sandy’s previous homeless shelter, Family Promise of Gainesville, followed a strict schedule. Around 6 a.m. families woke up and cooked breakfast. Each night, bedtime fell around 10 p.m.

But tonight, there wasn’t a schedule.

The first thing Millie does in any new space, whether that’s a cramped Sunday school room or makeshift tent, is clean. With a new broom, Kaboom and paper towels, they wiped, dusted and swept the apartment the best they could.

On the drive over Sandy realized they needed the basics, which included flour tortillas, ground beef and cheese for dinner and “Alien: Covenant” from RedBox.

He persuaded the Family Promise of Gainesville driver to break the rules and stop at Winn-Dixie.

Since they didn’t have living room furniture, the couple sat on the floor for their first dinner, Millie said.

“At least I knew the floor was clean.”

It was unfamiliar control. Cooking what they wanted. Sleeping when they wanted. Everyday luxuries they had long forgotten.

For homeless families like Sandy’s, moving into a home may often seem like as the end goal. But it’s not until those families move that they confront new challenges. Electricity bills. Phone bills. Holiday gifts. Furniture. Diapers. Clothes.

You’re still in poverty, and you still have to struggle every day.

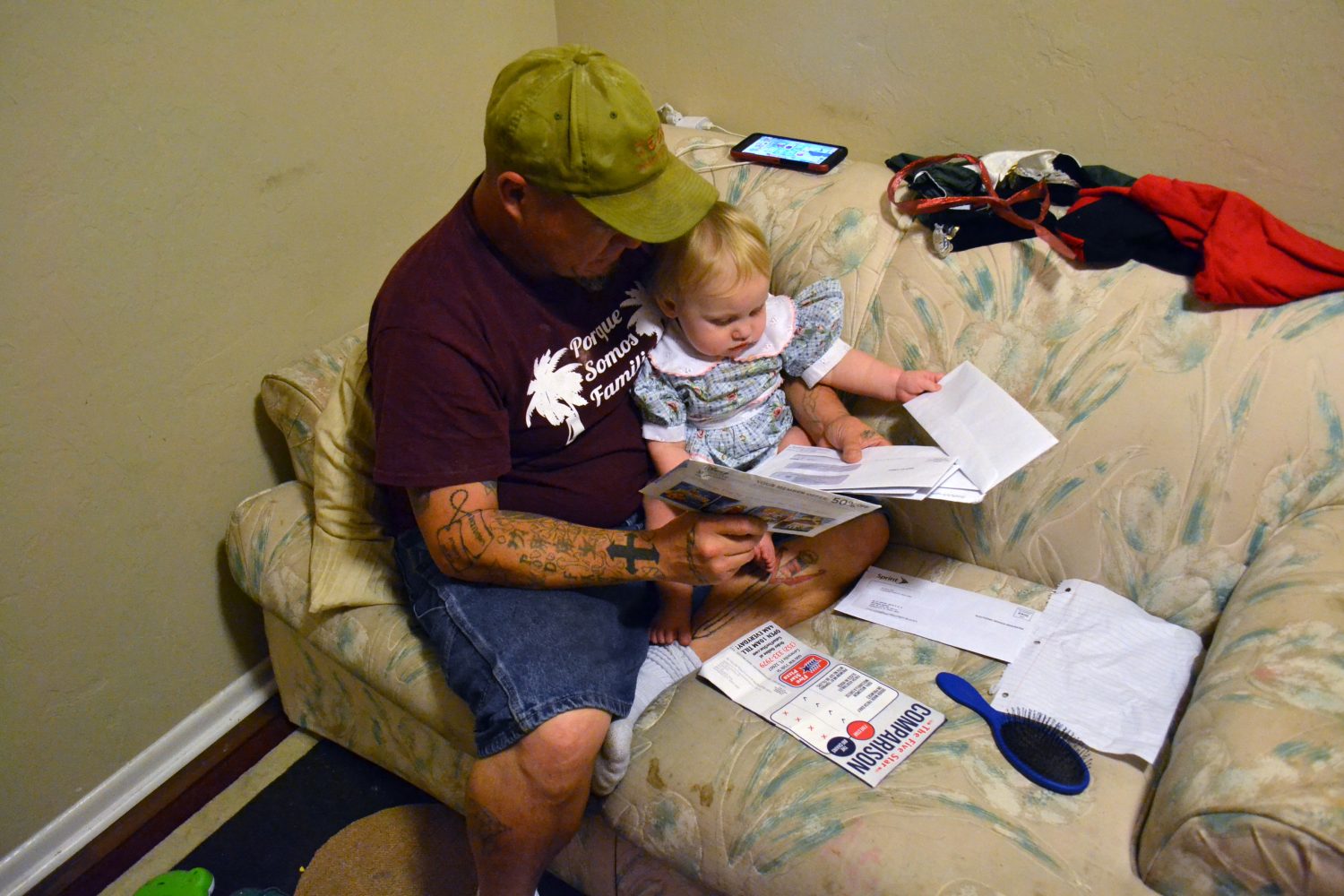

This fall, Sandy’s family moved into Majestic Oaks Apartments.

Family Promise of Gainesville, a nonprofit organization that helps homeless families find jobs, daycare, schooling and other services, was their last shelter before their new home. The nonprofit found Sandy a job at Nicopure Labs, a manufacturer for e-cigarette liquid. It found their daughter a pediatrician. It also found them the furniture that fills their apartment.

Jayne Moraski, the executive director of Family Promise of Gainesville, said families don’t recognize all the burdens of a home until they’re in one.

“Once you leave our program, it’s not as if you live the life of luxury,” she said. “You’re still in poverty, and you still have to struggle every day.”

The biggest challenge: The cost of things that families have never paid for.

Furniture, food, shampoo, soap, pots, pans, sponges, dishware, silverware, sheets, laundry detergent, a laundry basket, a trash can, a dinner table.

“We try our best to get families situated with the bare necessities they need, which can be in the thousands of dollars,” Moraski said, “But we can’t provide it all.”

Family Promise of Gainesville partners with churches and synagogues to offer shelter and food for four families. Families sleep in a church throughout the week, and at the end of the week, they’ll pack their bags and move to a new church or synagogue. During the day, families spend time in the organization’s day center. A mural of a painted tree fills one wall, which is an old home converted to a center crowded with couches, a TV, a computer and a dinner table big enough for 10 people. The program lasts 90 days long, and typically each family transitions into a permanent home at the end.

Shari Jones, Millie and Sandy’s case manager at Family Promise of Gainesville, meets with the families once a week to go over their progress. She said families aren’t often aware of the resources available to them.

“So many families are suffering in silence because they don’t know who to turn to,” she said.

Currently, Family Promise of Gainesville has an 18-family waitlist.

With the help of Family Promise of Gainesville and Grace Marketplace, a homeless shelter, Millie and Sandy signed a 12-month lease.

Their new apartment means hot meals, scalding showers and a warm bed. It means a place where extended family can visit and their daughter can grow. But it also means a $143 electricity bill every month, a $90 phone bill, and other necessities that aren’t covered by food stamps, such as diapers and clothes. In total, the family needs about $300 a month to survive.

Sandy had a hernia that needed a second surgery. He’s been on medical leave from his job for about three months and visits doctors weekly. Millie is looking for a job waitressing, housekeeping or “really just anything.”

Majestic Oaks Apartments is income-based, which means Millie and Sandy would pay a third of their income for rent. Since Millie and Sandy currently don’t have an income, their main worry is finding money for the few bills they have.

Three hundred dollars isn’t easy.

“We’re making it work,” Millie said.

But a quiet “barely” trails after her sentence.

Their main source of income is Sandy’s plasma donations. Twice a week Sandy grabs a grey sweatshirt, puts on jeans and heads to the donation center.

He makes anywhere from $20 to $50 per visit, depending on how much and how often he donates. The first five visits are $50. It drops to $20 for the next two visits and then goes back up to $35.

I mean we’re barely getting by.

He uses bus passes from Grace Marketplace to ride to the donation center, where he’ll spend about an hour and a half donating plasma.

“It’s a loud machine, but I don’t mind the noise” he said. “It’s the ending that’s the worst.”

At the end of donating plasma, a technician injects a saline solution to help the body replace the plasma. The saline is cold and runs throughout your entire body, Sandy said.

He makes just under $300 a month. The rest comes from a little savings and help from their family.

The first month strained them, agreed Millie and Sandy.

Initially the family just had a couch, TV and foldable crib. Plastic bins sat at the end of the couch to replace coffee tables.

a Humphries/WUFT News)

Throughout the month it grew to look for like a home.

A new white crib found a home in their living room and a rug now covers the dented floors.

“It looks lived in,” Millie said. “I like it.”

Their dishwasher remained empty because they couldn’t afford dishwasher detergent. A lamp in the corner of their living room didn’t have a light bulb because a lamp and overhead lights felt “excessive.” Vegetable oil, Ranch dressing, rice, mayonnaise, butter, sugar and flour all filled up the first grocery trip.

Plus they have other things to save up for, like a Halloween-themed birthday party for baby Sandy’s first birthday. That meant cake, black balloons, purple and green streamers and a ladybug costume. A trip to Dollar Tree for decorations cost $13.50. The cake from Walmart was $42.99. A ladybug costume was $15.09 from Walmart. The $71.50 wasn’t in their monthly budget.

Millie’s mom and their little savings covered the party.

“I mean we’re barely getting by,” Sandy said. “But we’ve managed to scrape up a few dollars here and there so we can still celebrate the holidays.”

While Millie is excited to get her mom’s old Christmas tree and lights, Sandy’s already thinking of the extra electricity bill.

“We’ll have the heater on and the lights on. We’ll probably need an extra few bucks for both of those.”

Millie wears low-cut jeans and T-shirts. Her hair is dyed red and a slight smile sits on her face. Her kind eyes show a desire to help whenever and however, whether that’s waking up early to cook breakfast or staying up late to babysit for a friend.

Millie was born in Detroit, Michigan, but she grew up with her grandma in Dixie County, Florida. When she turned 18, she dropped out of high school, ran back to Michigan, and married her fiancé in her mother’s basement.

Millie ended up homeless three years ago after she left her abusive ex-husband and moved into Another Way Inc., a shelter for domestic abuse victims. Once her two-week stay ended, she had no home and little family to turn to. A free tent and Grace Marketplace became her best option.

Millie lived primarily between Grace Marketplace and Jacksonville with her mother. Her mother lost her home and Millie’s tent was all she had. She turned to alcohol and a year later ended up in UF Shands emergency room with pancreatitis.

Sandy’s face looks older than it should, and a Mohawk sits on the top of his head. He’s spent his entire life working odd jobs but prefers to be under a hood of a car. Tattoos cover both of his arms—a dragon on the left and a cross, names and letters on the right.

Sandy was born in Little Rock, Arkansas. When he was young, his dad moved the family to Adrian, Michigan, for a job as a corrections officer. His dad owned a mechanic shop on the side, and any minute of free time, Sandy was underneath cars and propping open hoods. He still relies on the skills he learned in that shop.

He lived in cities throughout Michigan, Arkansas and Florida until he permanently moved to Ocala. In Ocala, he was a maintenance worker for his apartment complex. One afternoon, he was on a ladder, fell off and broke both his ankles.

Shortly after, Sandy’s mother died, and he needed to get to Ohio to regain custody of one of his daughters.

Unfortunately, he couldn’t afford a bus ride to get there, so he made it up to Gainesville and ended up in UF Shands emergency room because of his ankles.

Millie and Sandy met in the emergency waiting room. Millie was there because of pancreatitis and Sandy because of his two broken ankles. After spending hours in the emergency room, both were hungry and ready to leave.

They walked to the Subway and talked over greasy meatball sandwiches.

Millie learned that Sandy had come from Ocala and didn’t have a place to stay.

Sandy learned that Millie had a tent.

“I gave him two days,” she said. “And on that first night he broke my tent.”

“She was pissed,” Sandy laughed. “But luckily she pitied me and let me stay.”

“The first night I just felt bad for him,” she said. “After that, I started to like him.”

Shortly after Millie was pregnant. Millie and Sandy spent a majority of the nine months living with Millie’s dad in Georgia, but once baby Sandy was born, the family was forced to move out. They ended up homeless in Gainesville again.

Raising children wasn’t possible in homeless shelters.

For the past year Sandy and Millie have bounced between eight homes and shelters.

Before Family Promise of Gainesville, Millie and baby Sandy lived in St. Francis House and Sandy was at Grace Marketplace.

Sandy’s case coordinator, Leon, told them about an opening in Family Promise of Gainesville. So the couple packed up their suitcase of belongings and became one of the four families at Family Promise of Gainesville.

Three months later and luxuries are beginning to feel like the norm.

Millie started looking for a day job and wants to earn a G.E.D. In the meantime she wants a dog and another baby.

“Raising children wasn’t possible in homeless shelters,” she said.

But neither was the nap she took at 3 p.m. nor the pot roast in the crockpot.

For now, Sandy’s future involves waiting rooms. He isn’t sure how long it will take to recover from the hernia but hopes it won’t be more than two more months. For now he’s waiting in plasma donation lobbies.

The family mastered their new bus routes but they’re still mastering budgeting. They learned to hunt for coupons and cut down their grocery list.

Sandy expected a permanent home to be easy but parts are more difficult than he imagined, he said. He wants to get to the point where a dinner out or new baby clothes doesn’t impact how his family lives for the rest of the month.

“I have no doubt we’ll survive,” he said. “It just might be a hard road.”

Special Report from WUFT News

Special Report from WUFT News