By Emily Mavrakis | January 3, 2019

Self-defense an ‘underemphasized’ way to prevent sexual assault on campus

Ashley Vogt was tired and hungry. It was late at night, and the 21-year-old University of Florida theatre performance senior had just finished helping an intoxicated girlfriend get home safely from a party.

A male friend of Vogt’s offered to drive her to Taco Bell to pick up some food, then back to her apartment. Grateful, she agreed.

Vogt’s friend insisted on paying for her taco and drove her home. When they arrived at Vogt’s apartment complex, he asked to come inside to use her bathroom. Again, she agreed.

Once inside, Vogt recalls, the “friend” pushed her onto her bed, telling her “You wanted this to happen.” It was not the first time a guy had overpowered Vogt, a slim woman with long straight, blonde hair who is sometimes compared to Sarah Michelle Geller from the show “Buffy the Vampire Slayer.” As in previous experiences, Vogt froze up and couldn’t speak.

“I felt like I couldn’t even say no at that point.”

The man managed to pull her pants off and started touching her, but Vogt lied that she needed to go to the bathroom before anything else could happen. When she came back into the room, he had passed out.

After that night, Vogt stopped being friends with the man and ignored his texts. If she ever sees him while she’s out with friends, she avoids him.

Vogt’s tendency to freeze up is a common reaction to stressful events, but sexual violence prevention experts say women who learn to assert themselves and make their unwillingness to have sex clear can help prevent potential assaults from occurring or getting worse.

Research has shown that self-defense training is one of the most effective ways to reduce the number and severity of sexual assaults among college women. Whether or not women learn effective techniques for fighting off a would-be assailant, the classes improve a woman’s self-confidence, which can empower her to take charge of and escape from dangerous situations.

Shifting the focus to confidence

Vogt is not alone in her negative experiences with men. One in five women are sexually assaulted during their lifetime, according to the U.S. Department of Justice. College-age women are particularly vulnerable.

Universities in the United States are required by federal law to disclose the number of sexual assaults that occur on and around campus under the Clery Act, passed in 1990. However, an estimated 65 percent of sexual assaults and rapes, like Vogt’s, remain unreported, according to a 2013 report from The Bureau of Justice Statistics National Crime Victimization.

At UF, university police keep these reports for seven years, and UPD currently has data on reported sexual assaults from 2008—2017. The average number of reported sexual assaults over the past decade is 13. However, the number of reported assaults has been highest in the past three years, peaking at 25 in 2016.

But this number does not include information for any unreported crimes. Andrea Palmer, a UPD victim advocate, says it is impossible to have accurate data if survivors do not report a crime. She said the department offers free and confidential services for students both on and off campus.

“UPD strives to encourage victims of crime to report, while providing the services of Victim Advocates to educate the victims on their options and services provided to them, so they can make the decision that best suits their needs,” she wrote in an email.

Martha McCaughey, a sociology professor at Appalachian State University in North Carolina, says many university websites offer services to help survivors after a sexual assault has already occurred, such as providing information on how to report the crime, rather than showcasing preventative actions.

“It treats the assault like it’s a done deal.”

Trauma caused by assault multifaceted, long-lasting

One of the reasons so many women wait up to a year to report their sexual assaults, if they decide to report them at all, is because they often know the perpetrator.

Vogt says several of the men who have sexually assaulted her have been acquaintances or close friends whom she does not want to hurt.

“I don’t think they’re evil people,” she says. “I’ve never had any malice toward them because I don’t think they know what they did is wrong.”

Trauma from sexual assaults also can discourage women from reporting.

Cassandra Moore, the project coordinator for Alachua County Victim Services, says women often feel shame or guilt after a sexual assault.

“They feel they could have done something differently,” she says. That self-blame makes them less inclined to report the assaults to anyone, let alone the police.

“I don’t think they’re evil people,” Vogt says. “I’ve never had any malice toward them because I don’t think they know what they did is wrong.”

The long-term consequences of sexual assault for students in college, as identified by the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network, might include difficulty concentrating or sleeping, feeling depressed, and dropping out of classes or discontinuing activities where the survivor may see the perpetrator.

Sexual assault can generate serious mental health issues, including depression, suicidal thoughts and post-traumatic stress disorder, even several years after the event.

Dealing with the medical and legal ramifications of a sexual assault can be mentally taxing, says Moore, from Victim Services.

At Victim Services, a team of professionals and victim advocates help survivors at every step of the process, whether they want to complete a rape kit for DNA evidence at a hospital, report their situation to the police or attend therapy sessions.

“It can take the emotional burden off that survivor,” Moore says. “It’s just really beneficial to have someone there who can explain the process.”

McCaughey says having access to these types of programs is important to validate women’s situations and show them they are not alone.

However, the Appalachian State sociologist believes emphasizing how best to help survivors after they experience sexual assault – instead of preventing assaults from occurring – “is doing women a terrible disservice.” Instead, she says, universities and local governments should stress preventing sexual assault by empowering women through self-defense.

McCaughey says cultural contexts can lead to situations in which women, often college students, are assaulted.

In college, she says, the message to women often is that “you’re supposed to be a good-time party girl.” Heavy drinking, attending parties and hookup culture are often factors when an attempted or completed assault takes place.

Several of Vogt’s sexual assault experiences occurred either after a party or at a fraternity house, situations in which alcohol was available and peer pressure from other men can lead to competition for women’s attention.

Madeleine Coy, a professor at UF’s Department of Gender, Sexualities and Women’s Studies, says that although alcohol can play a supporting role in assault cases, alcohol should not be considered a “cause” of assaults.

“What I think we have to be careful about is not blaming alcohol for the assault taking place,” Coy says.

The blame rests solely on the perpetrator, she says. Alcohol, drugs or peer pressure may have played a role in escalating an attacker’s behavior, but it was still that person’s choice to pursue that action.

McCaughey agrees that an attacker is the only person who should be blamed for an assault. Nonetheless, she insists, women must not wait around for others to learn how to treat them with respect.

“It hasn’t worked for us.”

Waiting for men to change their behaviors creates a more codependent relationship between men and women, with men as the dominant force, McCaughey says.

“It makes it seem like men have the choice to assault a woman or not,” she says. “I don’t think that’s very empowering for women.”

Self-defense, best defense

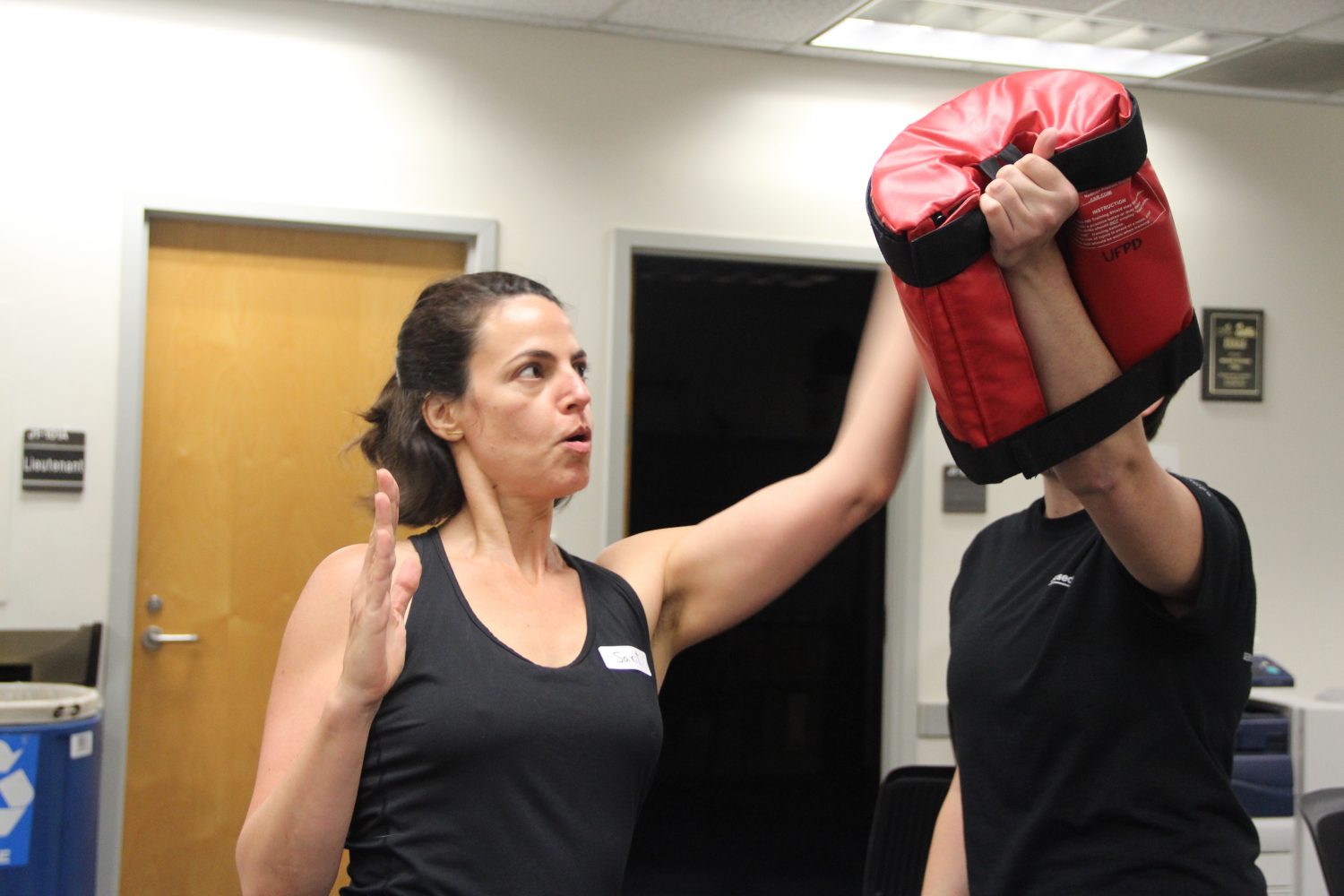

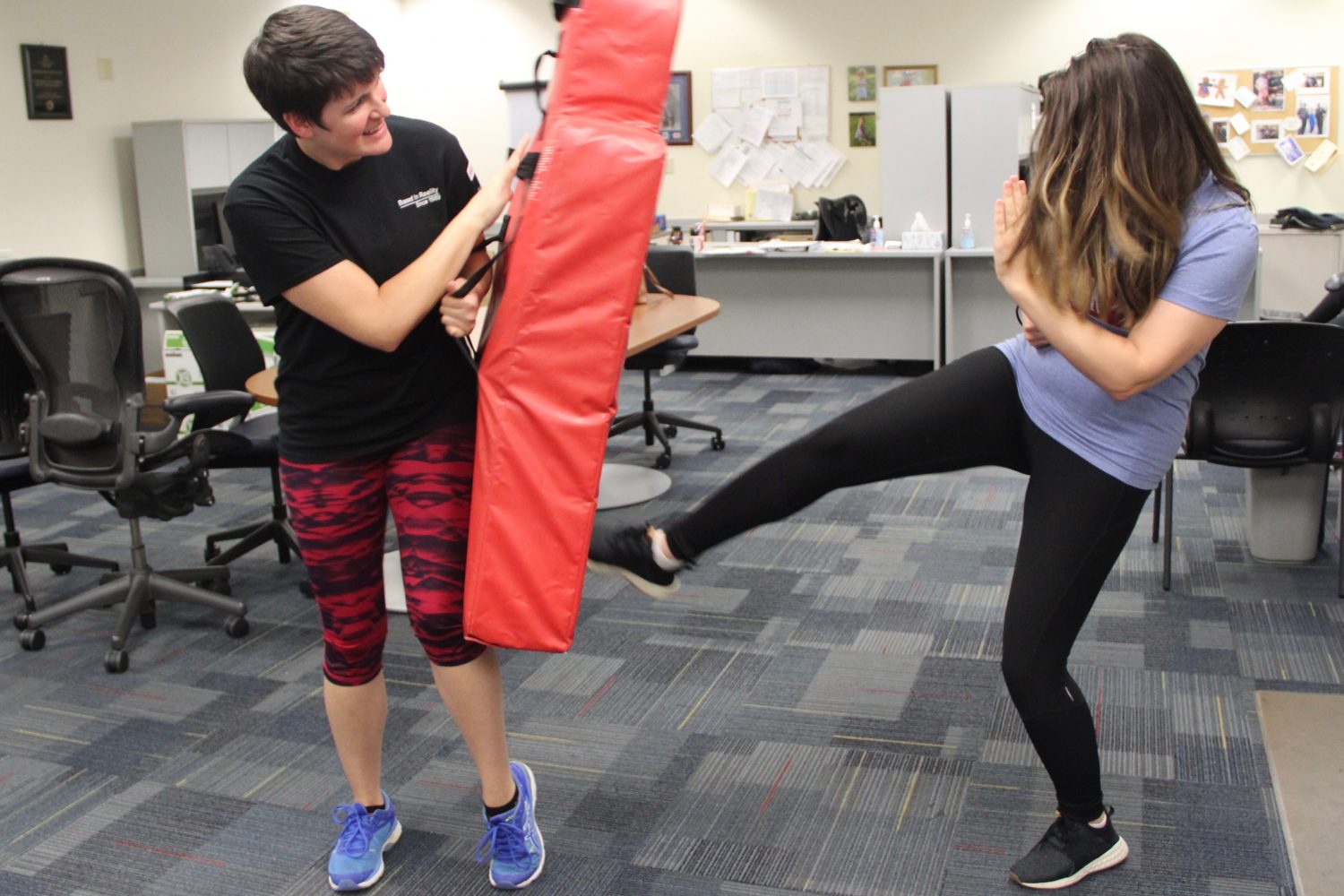

One evening in a classroom at UF’s police department headquarters, 39 women strike, kick and bash into 4-foot-tall red punching pads. Leading the group is Morgan Faroni, a butt-kicking brunette Tinkerbell with a short pixie cut and a soft-spoken manner.

Faroni is no damsel in distress. She calls out words of encouragement to the women as they practice self-defense techniques on the pads.

UF has taught Rape Aggression Defense, or RAD, classes since 1991. RAD is the nation’s largest self-defense training program, available in all 50 states. Hundreds of universities make it available free for students, usually through federal funding.

Research suggests that women who complete training are more confident in their abilities to stand up to aggressors, whether they are strangers, acquaintances or intimate partners.

In one University of Oregon study, one group of women received 10 weeks of self-defense classes and another did not. The groups completed surveys on their self-confidence and any sexual assaults they experienced during a one-year follow-up period.

About 12 percent of women enrolled in the self-defense classes reported a sexual assault, compared to 31 percent of the control group. In addition, the average severity of the sexual assaults was lower in the self-defense-trained group.

Most participants in UF’s fall 2018 RAD class are young college students, encouraged to join by their parents who heard about the program at the school’s freshman orientation, but others are adult faculty and staff at the university or other members of the public.

Faroni, UF’s RAD program coordinator, says she thinks every woman could benefit from participating in the program early in her college experience, although not everyone has the mindset or confidence to complete it right away.

Above all else, Faroni says, knowing your own abilities and limits can empower women to take charge of potentially bad situations.

“Trust us, but more important, trust yourselves,” she tells the RAD students.

In Gainesville, the program is free not only to students, but to women of all ages who want to participate in the four-session training. Each session lasts three hours, and a participant can complete all four in as few as two weeks. If she chooses, she also can return at any time afterward to practice the techniques at another training.

Faroni says the greatest outcome participants gain is increased self-confidence in using their own skills—no buddy system, pepper spray or stun gun needed.

“You already have the answers but have not taken time to realize it yet,” she says. “That strategic mindset is really helpful.”

Opposition to self-defense programs usually stems from the suggestion that it puts the initiative, and therefore the blame, on potential victims and survivors.

Appalachian State’s McCaughey says this is not the case.

“It’s something people are worried about, but we’ve never had any data that suggests people actually feel that way, blaming a survivor.”

McCaughey says people also worry that self-defense training focuses too much on individuals, rather than focusing on a societal change. But changing society will take generations, she says, and women need to be able to protect themselves now.

“I would rather see them prepared for it,” she says.

Vogt has never enrolled in a self-defense class and says she is afraid of using violence against other people. But she has begun to address what she thinks is a major problem: her inability to say no and assert herself when she feels uncomfortable. The importance of gaining self-confidence is the major takeaway from the University of Oregon study.

“I’m working on getting more comfortable expressing my feelings,” Vogt says.

McCaughey cautions that it is important to understand that self-defense is not a foolproof solution that will ensure a sexual assault never takes place.

“It doesn’t provide any guarantee,” she says.

Faroni, holding up punching pads for the RAD class, watches as the participants become more assertive in their movements as they call out “No,” and “Stay back.” She agrees with McCaughey that preparation is crucial.

“We can’t control how people act, but what you have available and using that is the most important.”

Special Report from WUFT News

Special Report from WUFT News