An 11,000-acre phosphate-mining operation proposed near the New River in rural Union and Bradford counties reveals that no corner of Florida is immune from the pressures of development and growth.

A dusty dirt road turns into a paved street at Elzey Chapel Cemetery in Union County. Some of the white, weathered gravestones on the grassy hill predate the Civil War. On a sunny day, the newer granite markers reflect the oak trees and clouds in the sky like pools of still water.

Courtney Snyder stands next to her family’s plot, where her grandfather and uncle are buried. As she watches her two daughters, five and seven, race to the other side of the cemetery, Snyder brings her sparkling nails to her mouth to take a drag of her TIME cigarette, then taps it into the ash tray she carries with her so as not to litter.

Snyder, a stay-at-home mom who writes fiction in her free time, was born and raised in Union County, the smallest county in Florida by population and landmass. She figured it was where she would raise her two children and die.

Then in January 2016, Snyder came across a Facebook post that threw her plan into question. A contingent of four of the largest landowning families in Union and neighboring Bradford County had come together with the intent of mining approximately 11,000 acres for phosphate, a primary component in agricultural fertilizer found in deposits throughout Florida. The initials of HPS Enterprises, the company behind the mine, stands for the four families: The Hazens, Howards, Pritchetts and Shadds.

Through subsequent county commission meetings, residents of Union and Bradford learned that over 20 years, the proposed operation would systematically dredge up the familiar farm land on either side of the New River, a 31-mile-long tributary to the Santa Fe River that forms the county line. The pasture across from Snyder’s trailer would be mined. Elzey Chapel Cemetery would be surrounded.

HPS officials promised the mine would bring millions of dollars to both counties as well as jobs, a significant vow in Union, with the lowest per-capita income in the state. The company also promised it would invest in new technologies to avoid blighted clay-settling ponds and the exorbitant groundwater pumping for which the industry is known.

But residents of both counties weren’t convinced. They fear the mine could decrease property values and despoil the New River, whose snaking brown waters are dotted with cypress knees.

“Most of us who are against this mine, we’re just people that live here that want to preserve our way of life,” Snyder said. “We don’t want to feel like we’re being run out of our homes.”

Photographs by Ryan Jones.

In 1977, Jim Tatum and his wife, Ruby, began making excursions to the Santa Fe River to dive into its tannic waters, braving snapping turtles and water moccasins, for fossils. The bones of mastodons, giant armadillos and saber-toothed cats are traces of the millions of years of geology that shaped Florida’s interconnected system of wetlands, rivers and springs, and created the phosphate deposits mined today.

Sixteen years ago, Tatum retired and moved to a place on the river near High Springs. Now the historian for Our Santa Fe River (OSFR), an environmental advocacy organization, Tatum believes HPS’s proposed mine would put the river risk.

“It’s the driver of our economy around where I live,” Tatum said. “If all these springs were dead, if the river were dead, it would be a dead place up here.”

As integral to the state’s economy as citrus or Disney, phosphate has been mined in central Florida’s Bone Valley for over a century. But urban population growth, increased demand and feared shortages of phosphate globally have renewed the industry’s interest in North Florida.

HPS’s proposed operation is smaller than a typical phosphate mine — 1.2 million tons of phosphate rock would be dredged up annually, compared with the average of 3 to 5 million, according to a company presentation. But residents and environmentalists worry this area of Florida is too fragile for a phosphate mine.

Dennis Price, a hydrogeologist whose consulting firm reviewed HPS’s proposal for OSFR, noted that as commercial phosphate mining took hold in Central Florida in the mid-1900s, wetlands and cypress swamps in the north were drained for the pine plantations that checker Union and Bradford counties today. Without wetlands to capture rainfall, less water can return to the Floridan Aquifer.

“All along the St. Johns River, you could drill a hole 20 feet in the ground and it would shoot up in the air, just like an oil well,” Price said. “That’s how much pressure we’ve lost.”

Price lives in White Springs in Hamilton County, home to North Florida’s largest phosphate mine. Now owned by Nutrien, a global corporation based in Canada, the 100,000-acre mining complex has been in operation since 1965. At its height in 1980, the mine employed over 2,100 people in North Florida, said Mike Williams, Nutrien’s director of public affairs. Today it employs 630.

“It became the job to get and the job to keep,” said Helen Miller, a former city commissioner.

Miller said hoped-for economic development did not materialize. The mine has remained one of the largest employers in the area, but the local economy is at the mercy of the cyclical global phosphate industry. Every few years, hundreds are laid off, only to be hired back months later. Meanwhile the hills of a radioactive byproduct of fertilizer production called phosphogypsum loom off U.S. 41.

Though the millions of dollars of property taxes have been invaluable, Miller said there has been a noticeable impact on the spring that gave the town its name and drew thousands of tourists a year.

“‘The spring pours forth 20,000 gallons of sulfur water per minute,’” Miller said, quoting an 1883 advertisement for White Springs. “Now that spring provides a gentle flow; and for a number of years, the spring didn’t flow at all.”

Miller also noted that a number of accidents have occurred at the mine since 2000, such as acid spills from the lakes atop the stacks. Earlier this year, approximately 200,000 gallons of phosphoric acid spilled due to equipment failure, according to the Suwannee Democrat. The spill was contained onsite.

“The company does what it can to mitigate the problems—none of this is intentional,” Miller said. “They do try to be good environmental stewards, they do employ current technology, and they have a very big focus on safety. However, accidents occur.”

In January 2016, Becky Parker was at her 87-year-old mother’s house in Union County when the weekly local paper hit the front steps. Parker, who has spent most of her life in the county, doesn’t usually get the Union County Times, but she brought it inside and unfurled the paper. The proposed mine was front-page news.

“It was almost, at that point, like a done deal,” she said. “This was knocking-on-the-door about to happen.”

Alarmed, Parker spent the night researching the phosphate industry. By the time she was done, she felt she needed to do what she could to stop the mine. “The more I found out, the more upsetting it was,” she said. “That’s what lit the fire.”

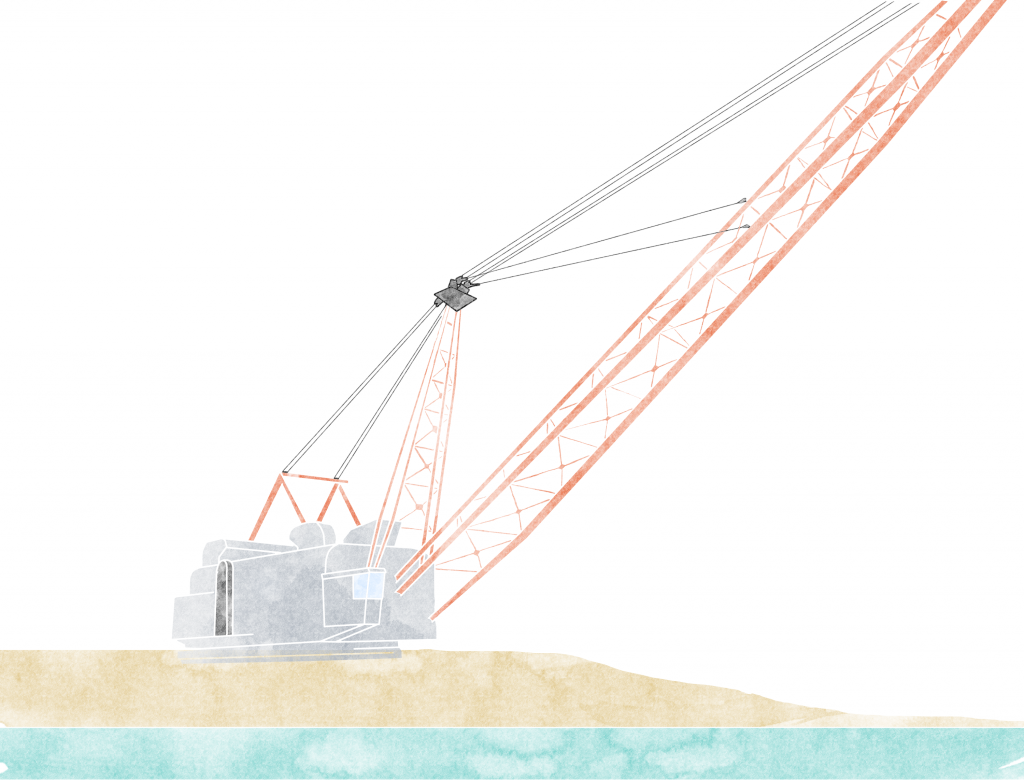

The next day, Parker created a Facebook group to organize local residents, a GoFundMe to raise money to fight the mine and an online petition to spread the word. Soon, bright red stop signs demanding no mining lined the highways, and white banners depicting draglines and moonscapes were nailed to abandoned buildings. Members from the Sierra Club and OSFR contacted Parker as her petition gained over 1,500 signatures from inside and outside Union County.

“This was a quiet, sleepy little town before all this happened,” said Carol Burton, one of Parker’s neighbors. The two women live in The Groves, a subdivision in Lake Butler named for the pecan trees that line the main dirt road. The road dead-ends at a rusty mental fence; the farm on the other side could become part of the phosphate mine.

The mine is personal in part because it’s local. The Department of Corrections is the largest employer in the county, but the four families behind the mine — the Hazens, Howards, Pritchetts and Shadds — are close behind, their multiple businesses offering hundreds of jobs in farming and trucking.

Even those who don’t work for them are personally connected to the families, which have donated to numerous charities and hospitals in North Florida, and supported churches and the local schools. About 50 years ago, the Howard family helped build Harmony Free Will Baptist Church, which Courtney Snyder’s grandmother attends. More recently, the Howards helped repair fire damage to the church.

That is why Snyder said the mine feels like “betrayal from the wealthiest.”

“There’s a lot of people in the community that don’t speak out because they feel like they’ll lose their job,” she said. “I don’t think anybody’s gotten divorced over it yet, but who knows at this point.”

As Parker’s ad hoc group of citizens in both counties grew, they decided to form Citizens Against Phosphate Mining. Through the organization, residents have persuaded the nearby towns of Brooker (where the mining would start), Hampton, Raiford, Worthington Springs, High Springs and Waldo to adopt letters of concern or sign resolutions against the mine.

Alachua County is also concerned about the mine’s impact on wetlands in North Florida given historic losses. Chris Bird, director of the Environmental Protection Department, noted that the proposed mine contains approximately 5,000 acres of wetlands. “They’re going to have to destroy a lot of wetlands in order to mine,” he said.

Union County held its first meeting about the mine in mid-February 2016. County Attorney Russell Wade explained the process for a mining permit to the board and the residents in attendance, which included Parker and her neighbors in The Groves.

If HPS were to submit a mining application, Wade explained, the commission would be required to consider it like a judge would, in a “quasi-judicial” process. This meant that not only would the commissioners have to consider factual evidence above emotional appeals, they would also not be allowed to talk about the mine outside public meetings.

This led every commissioner on the board to disclose that they had received calls from members of the Pritchett and Hazen families, and by representatives of the mine, to meet.

“I was not informed on what the meeting pertained to, I asked specifically, and they said they would just like to have a discussion with me,” Commissioner Jimmy Tallman said. “… After a short, brief meeting, I excused myself.”

In March 2016, Union County held a special meeting for company representatives to speak to citizens. Julian Hazen — whose cousin, Jack Hazen, is the principal behind HPS — drove up from his home in Bartow. An aging man, Julian has spent his career working for the Florida Industrial and Phosphate Research Institute, a state-funded agency tasked with researching better ways to mine phosphate. “I’m probably the reason all of you are here tonight,” Julian began, turning from the lectern to face the audience.

Julian said that around 2011, he had approached Jack, who knew his land contained phosphate because he bought it from Kerr-McGee, a chemical company that had intended to mine but ultimately decided it wasn’t profitable. Julian said he asked his cousin whether he would consider mining if there was a way for the land to be agriculturally productive afterward.

With technology he had spent the last 20 years developing, Julian said he believed it would be possible to mine the land without pumping large amounts of water or constructing clay-settling ponds, which have little ecological or agricultural value. According to Julian, the mine could indirectly offer everything from higher life expectancies to good jobs.

Ultimately, Julian said that because the United States is running out of phosphate rock, “Someday, this deposit will be mined,” Hazen said. “Whether it’s 5 years from now or 20 years from now.”

Three days later, residents swelled on the brick sidewalk outside Union County’s courthouse, waving signs with “save our springs” and “you can’t drink money” scrawled in brightly colored marker.

Inside the chambers, Snyder picked past reporters to find a seat. She could feel the tension. Members of the four families, representatives of HPS and their lawyers sat by themselves in the first few rows. Residents sat behind them, waiting for the commissioners to call the meeting.

“It was like a shotgun wedding,” Snyder said.

Both counties realized in early 2016 that their comprehensive plans, a collection of policies that regulate development, weren’t equipped for an industrial project the size of HPS’s proposed mine, even if that mine is relatively small. At the time, land development regulations in both Union and Bradford allowed mining in wetlands as long as the land could be reclaimed or restored.

At the recommendation of the North Florida Regional Planning Council, Union County had decided to vote on whether to place a moratorium on mining permits so it could revise its land development regulations to better protect the wetlands.

After the meeting was called to order, HPS representatives gave a presentation opposing the moratorium. They promised the mine would bring $156 million a year to the regional economy and create 152 direct jobs. There was no need for new regulations, they told the commission, as there would be no gypsum stacks and no clay-settling ponds.

“It’s OK to have concerns. This is a new activity. It’s a large project for a small community,” Timothy Riley, an attorney for Tallahassee-based Hopping Green & Sams, which represents HPS, said at the meeting. “But it’s not an unanticipated activity. Your existing regulations and community laws already address phosphate mining activities.”

When HPS finished, shouts of “no mining” broke out. At the end of the night, Union commissioners voted unanimously to declare a moratorium, which they would finalize in subsequent meetings. Three years later, that moratorium is still in place as the county works to finalize its new land-development regulations, which will prohibit phosphate mining in wetlands.

But the moratorium might be costly. HPS recently filed a claim under the Harris Act against Union County for over $289 million, alleging the county extended the moratorium and amended its regulations “to expressly prevent” the company from mining.

“Before the Comprehensive Plan Amendment, HPS was able to mine 2,757.6 acres,” according to an October letter from Hopping Green & Sams. “After the Comprehensive Plan Amendment, which expressly prohibits mining in areas that were previously allowed, HPS is only able to mine 341.0 acres.”

“There’s a lot of people in the community that don’t speak out because they feel like they’ll lose their job. I don’t think anybody’s gotten divorced over it yet, but who knows at this point.”

Union County native and mine opponent Courtney Snyder.

Bradford County also considered a moratorium, but commissioners ultimately voted against it in late March 2016. A month later, residents packed the commission chambers in Starke. Nineteen people stated their opposition to the mine, including Steve Piezenik, a retired physician who lives on Lake Santa Fe with his wife, Stasia Rudolph. The stocky, graying man spoke about the possible effects phosphate could have on water in the region.

“A mining company is a declaration of war, it is not simply a declaration of business,” he said, returning to his seat to applause.

Toward the end of the meeting, an expletive punctured the commission’s discussion. All heads swiveled to where Piezenik was sitting. Jack Hazen and another man were leaning over Piezenik, who suddenly stood up and pointed a finger in their faces. Piezenik was asked to leave the chambers. When he refused, he was forcibly removed as his wife followed, repeating “they went to him.”

But residents had bigger problems. At that same meeting, Bradford commissioners revealed HPS had already submitted an application for a mining permit: The discussion of the moratorium was moot. According to county ordinances, the commission was now a quasi-judicial body. The commissioners could no longer comment on the mine outside public meeting.

“We’re a small county,” said Bradford County attorney Will Sexton. “When people here have a problem, they don’t think twice about calling their elected representatives. When they hear they can’t talk to their county commission about this issue, that’s frustrating. … The goal is not to frustrate, the goal is to give everyone a fair shot at a decision based on only facts and not bias.”

But residents like Carol Mosley, who had brought written questions for the commissioners that night, felt forced to look for answers on their own. Mosely, who lives in tiny Graham in Bradford County, is now constantly requesting documents about the mine from the county and the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. She drinks coffee at 9 p.m. to spend hours poring over documents with a magnifying glass that’s nearly the size of her face.

“We’ve been told, ‘oh, you’re not gonna stop it, the people are too powerful, this is an area where decisions have been made via the good-old-boy network,’” Mosely said. “This is not a comfortable position to be sitting in. But we just happen to be old and with a lot of gumption.”

The protests have mostly died down as residents wait for the results of a review ordered by Bradford County. When Jacksonville-based Onsite Environmental Consultants submits its report on the mine application, likely in early 2019, residents will have 90 days to prepare for the vote on whether the county will accept or reject it.

“We expect that no matter what the decision is at this hearing, there will be a lawsuit,” Mosley said.

She and others imagine a more-sustainable future in the land that might be mined. She recently formed the Bradford Environmental Forum with other concerned residents to advocate for wetland restoration, environmental education and ecotourism in the region. They want to buy Brooks Sink, a sinkhole on land currently leased for hunting by Rayonier, a timberland real estate company, that is allegedly more wondrous than Gainesville’s Devil’s Millhopper.

Back at Union County’s Elzey Chapel Cemetery, Snyder said that as much as she loves her home, she has a new plan if the mine is permitted.

“I’ll move; I’ll leave,” she said. “I don’t want to leave. This is my home. … But if they go to mine across the street from me, I’ll have to leave.”

Peak Florida

Peak Florida