By Briana Erickson | February 17, 2017

Nearly 40 years apart, two men search for peace—together.

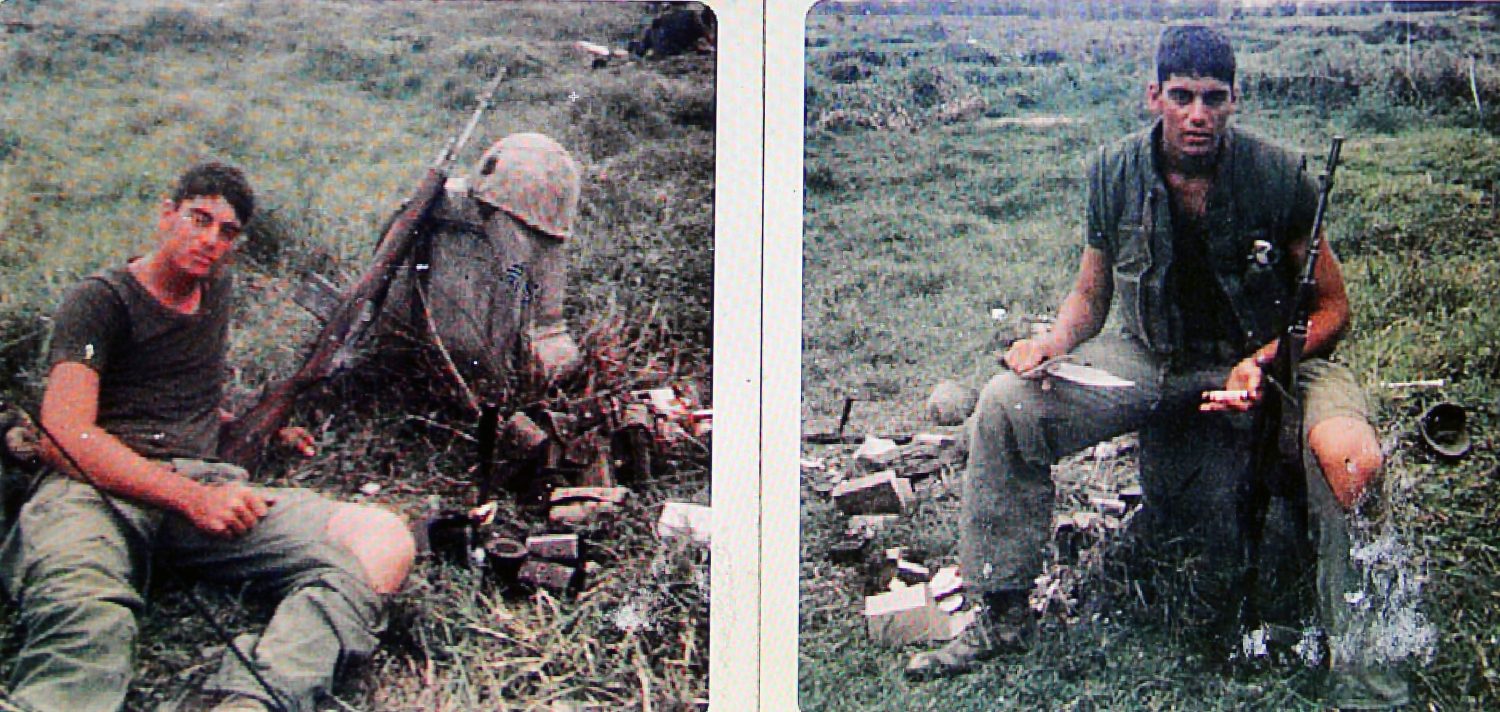

It was 1965. The time of the Vietnam War — and the draft.

“You can get a better deal if you sign up now,” the Marine Corps recruiters told students at Hialeah High in Miami-Dade.

Scott Camil opted for the better deal. Three days after graduating, he departed for boot camp. He said he wanted to be a man. One who did things. One who could be counted on. One who wasn’t a sissy.

“The Marine Corps. builds men,” they said. Camil wanted to prove himself a man in battle.

In 2003, 23-year-old Joe Sens rode his bike to a Maryland armed forces recruiter station.

“How would you like to jump out of airplanes for a living?” the recruiter asked him, prepping up a sales pitch for the United States Army.

Sens said he wasn’t sure if he wanted to jump out of airplanes. But he was drawn to find out.

***

Camil and Sens entered different wars — nearly 40 years apart.

Camil said he felt it was the right thing to do; it was his duty to fight communism.

Sens wanted to be a part of something.

They both ended up in Gainesville, each damaged from the post-traumatic stress of battle. The two wars shaped their lives as civilians. Each day, they work to reconnect with empathy, themselves and the world around them.

For Camil, 70, that means fighting against war, protecting the environment, campaigning for local politicians and doing what he can for his friends.

For Sens, 36, it’s living with his brother, his wife and their 3-year-old son, growing his own food and trying to find himself.

***

When Camil went to war, he had one rule: He would rather come home dead than without legs or the ability to have sex. When he did come home alive, all body parts intact, he said he couldn’t understand why some people lived, while others were killed.

Camil remembers introducing himself to the men on his first day in the unit Alpha North. He met Jake from Jacksonville — a comforting reminder of Florida, and his first friend on the new terrain.

But in the early hours of April 18, 1966, an explosive flare went off at their camp, illuminating the night and signaling Camil’s first combat against the Viet Cong. Twenty-eight Americans were wounded and five killed. When the sun came up, Camil put a bullet in the heads of the 40 dead Vietnamese. The bodies made a line on the ground.

When Camil got to the end, he walked over to the five dead marines and pulled their ponchos off to see their faces. He recognized one of them as Jake.

He stopped.

War is not going to be as much fun as I thought it would be.

***

To this day, Sens battles post-concussive syndrome, traumatic brain injury and hearing loss. Being labeled as “unemployable” allows for him to receive compensation from the Department of Veterans Affairs and disability from Social Security.

Sens’ injuries stem from his first deployment. He remembers the fierce and steamy weather in Baghdad. He drank close to three gallons of water a workday. The air, warm from the blazing Arabian sun, whipped his face like a blow dryer. The day he got injured, he wore desert camouflage. He remembers seeing a Kia Hatchback pulled to the side of the road with its hood up, and the civilians pouring water into the car’s radiator. Next, an explosive flash. The hairs on Sens’ head stood up; the brown wool wrapped around his forehead scorched. Everything went dark.

When he woke up 10 minutes later, a medic stood over him. He smelled smoke. He couldn’t hear himself talk, but he asked anyway.

“Why am I smoking?”

***

Camil was raised in South Florida. His family lived on food stamps. As a young Jewish boy, he would get harassed by his classmates.

“Jesus killer!” they’d call him. That’s when he learned to fight.

Camil remembers his old friend, John, from high school. He was a good boy, Camil said. He was Catholic, his parents were strict, and he did his homework. John was everything Camil thought he was supposed to be.

In Vietnam, while walking to the mess hall for dinner, John called to him, “Hey, Scotty!”

“Who’s calling me Scotty?” Camil thought. “I’m Corporal Camil now.”

John was the new guy, and Camil had been there about a year. “New guys make mistakes,” Camil said. So Camil asked people to keep an eye on John. He wrote John’s parents, telling them he would take care of their son. One day, Camil got a call from a man in John’s company. John was hit by a sniper, paralyzed and later died.

“I wondered, ‘Well, why did he get killed? How come I didn’t get killed? He was the good person, and I was the bad person,” Camil said. “That’s always bothered me.”

***

Sens’ dad, a Jehovah’s Witness, had rules for his teenagers. No smoking pot. No missing school.

His father wanted him to finish school, but Sens liked working. At 14, after his parents’ divorce, he got his first job. At 16, the adolescent with the dark curly hair moved out and worked as a cook at a Ruby Tuesday’s. At 17, he dropped out of high school and got his GED certificate. After working most of his adolescent life, Sens signed up for the Army at 23.

“I wish you wouldn’t do this,” said his religious father, who felt his middle son was destroying the standing in the religion he grew up in.

In 2015, Sens moved to Gainesville with his wife, Jessica, and son, Darwin. To this day, he still struggles with PTSD. When he enters a room, the reserved man with the salt and pepper beard looks for a seat in the corner. He says it’s so nobody can come up behind him. Noises keep him up at night. Wherever he is, when he starts to feel his heart race, he leaves.

***

It wasn’t until the 1970s that Camil said he figured there was one reason he came back from Vietnam alive: to fight for peace and justice. He still lives in the same Gainesville home he bought in 1979. From his nearly 11 acres off Williston Road, he’s planted azaleas, orchids and other plants, as well as hosted Sunday volleyball games for at least 30 years.

He roams his property shirtless, walking about the yard watering plants, a gold chain dangled around his neck and pants pulled up to his belly button. He punctuates his sentences with profanity, demanding all his guests feel comfortable enough not to knock.

Camil said he uses the money he gets from the federal government to fund his activism. He serves as political chair of the local Sierra Club and president of the Gainesville chapter of Veterans for Peace.

Alachua County Commissioner Mike Byerly named his 3-year-old daughter, Camille, after the activist, who worked on Byerly’s campaigns. They consider each other family.

Camil’s activism stems from what he realized after his 600 days in Vietnam. He’d heard stories about his Jewish family members killed in the Holocaust. After leaving the marines and attending school, he said he realized he had done the same in Vietnam.

When Camil transferred to the University of Florida, he had long hair and a thick beard. He looked much like other hippies of the time who thrived off feel-good music, sleeping around and getting high. But he was a skilled marine, whose testimony involved burning villages and dropping napalm.

He helped start Vietnam Veterans Against the War. They testified before Congress. They spoke in schools, churches, synagogues, and had demonstrations all over the country. VVAW grew from 2,000 to 50,000 members.

By 1973, Camil made J. Edgar Hoover’s list to be “neutralized” for his involvement with the VVAW. Later, he became part of a group titled the Gainesville Eight — protesters indicted for planning to violently disrupt the 1972 Republican National Convention in Miami. The group was later acquitted in federal court.

After the Gainesville Eight case, Camil moved out of town, returning quietly and living in a house under his friend’s name. One day, a woman came to the door, her fingernails polished, her hair and makeup done.

“She was dressed to kill,” Camil said.

The two got high and slept together. One Friday, two men she introduced as her friends came to Gainesville and said they were going to pick up drugs. They asked Camil, “Do you want some?”

On the way back, the man in the back seat grabbed Camil around the neck, pinned him to the headrest and stuck a gun to his head repeatedly. Camil seized the man’s wrist, held his hand to the headrest and unlocked the passenger door to jump out. That’s when the driver slammed on the brakes, grabbed Camil’s arm and freed the gunman, who then shot Camil in the back.

Camil still has the bloody shirt he wore the day he got shot in 1975. “It’s history. It’s evidence,” Camil said. “The report said I got shot in the shoulder, but when you look at the shirt, it’s proof that I got shot in the back.” (Briana Erickson/WUFT News)

Camil still has the bloody shirt he wore the day he got shot in 1975. “It’s history. It’s evidence,” Camil said. “The report said I got shot in the shoulder, but when you look at the shirt, it’s proof that I got shot in the back.” (Briana Erickson/WUFT News)

The bullet went through Camil’s shirt and lodged in his abdomen. The force of the gunshot lifted him out of his white tennis shoes. He suffered shattered ribs, a collapsed lung and kidney and liver damage.

The two men, agents for the Drug Enforcement Agency, charged Camil with assaulting federal agents, possession and delivery of drugs and resisting arrest with violence. He was later found not guilty by a federal jury. The agents were never charged. Camil still has the bullet and bloody shirt from that day in 1975.

“It’s history. It’s evidence,” Camil said. “The report said I got shot in the shoulder, but when you look at the shirt, it’s proof that I got shot in the back.”

Since then, Camil has lowered his sights in fighting for justice, but he’s “still fighting the same fight.”

“My ‘girlfriend’ was assigned to come here, meet me and have really good sex,” Camil said.

But, it was all part of a plan to shoot me.

***

When Sens returned to the states, he still felt deployed.

“Everything is so different in civilian life, it’s like people move really slow or something,” Sens said. “You almost feel like pushing people out of the way.”

After returning from Baghdad, Sens worked a middle-management position at the Hilton Garden Inn restaurant in Atlanta. He remembers struggling to tell team members how to do something. “This isn’t the army, Joe,” they told him.

“I don’t know what that means or what I’m doing, but it came apparent to me that I didn’t fit in,” Sens said. “So I went back to what I already knew, which is the Army.”

But he never made it through the psychological part of his pre-deployment health assessment. He was suffering from PTSD, and the Army knew it.

“I knew my Army career was over. I just didn’t know how I felt,” Sens said.

I still don’t know; I’m still trying to figure it out.

After being discharged in 2012, he moved to Montana, primarily because the state had the lowest population per square mile. He looked for tranquility, to get grounded, to figure out what he needed to do.

A year later, his wife got pregnant. They moved to Mississippi to be close to his mom. In 2014, they moved to Spokane, Washington. Sens said the recreational marijuana in Washington calmed him down and remedied his PTSD. He plans to seek a prescription for medical marijuana now that it’s legal in Florida.

“It does help me be kind of normal,” Sens said. “So I don’t have to be worried, like ‘What’s that sound?’”

In 2015, Sens and his family moved to Gainesville, where the weather gives him an opportunity to grow his own food.

Sens moves every year. He said he has to see what’s over the hill. He’s still trying to find himself. He can’t stand sitting in his house. And he can’t run away from his problems, he said.

“I wonder how those Iraqis feel,” he said. “They don’t get to go home. They’re stuck.”

***

When Sens moved to Gainesville, he reached out to Camil.

“I’m a veteran, and I’m for peace,” he told him.

“Come on over.”

On a recent Sunday, the two men, their wives and a few other friends gathered at Camil’s house. They celebrated Darwin’s third birthday.

The little boy toddled around the living room with a pink toy lawn mower. He was dressed in a blue button-down shirt, a pair of yellow butterfly wings tied to his back. His curly blond tendrils resemble his father’s darker ones.

“Two is better than 3!” Darwin squealed about getting older.

Touching his father’s lap, he pointed a fork at him as he shoveled chocolate birthday cake into his mouth.

“Are you pointing a fork at me because you love me?” Sens asked from his seat in the corner of the room. He smiled at his son, a dimple rippling through his cheek.

“I thought he wanted to eat you,” Camil said with a chuckle.

Camil wore his hair in a silver ponytail. A gold hoop earring pierced his left ear. He sat on the couch, eating vegan birthday cake and sitting among his friends.

A song came on. “Norwegian Wood” by The Beatles. It took Camil back to Vietnam. A Navy Corpsman who died in the war played it on his guitar every night. The man’s name escapes him.

That’s what disturbs him the most. When he can’t remember the names of the dead.

Special Report from WUFT News

Special Report from WUFT News