The Clean Water Act of 1972 cleaned up the sewage pollution that once fouled waters from Biscayne Bay to Escambia Bay and across the nation. But extreme rains and more-severe hurricanes brought on by climate change, along with aging infrastructure, have sent hundreds of millions of gallons of sewage into Florida’s waters and communities.

Since the turn of the 21 century, more than 2.4 billion gallons of wastewater spewed across Florida, according to state records.

Sewage spills seeped across land and gushed into rivers, lakes and coastlines. As sewage infrastructure ages, broken and failing equipment coupled with the worsening weather wrought by climate change can harm the environment and people exposed.

Passed half a century ago, the Clean Water Act made a world of difference in cleaning up sewage filth across the nation. Municipalities could no longer dump waste into bays and other waters. But sewage plants and pipes built in the wake of the law are wearing. Florida’s population is booming. And the extreme rains, stronger storms and rising seas associated with climate change compound stress on the systems.

WUFT obtained data spanning more than 20 years on wastewater pollution reported to the Florida Department of Environmental Protection.

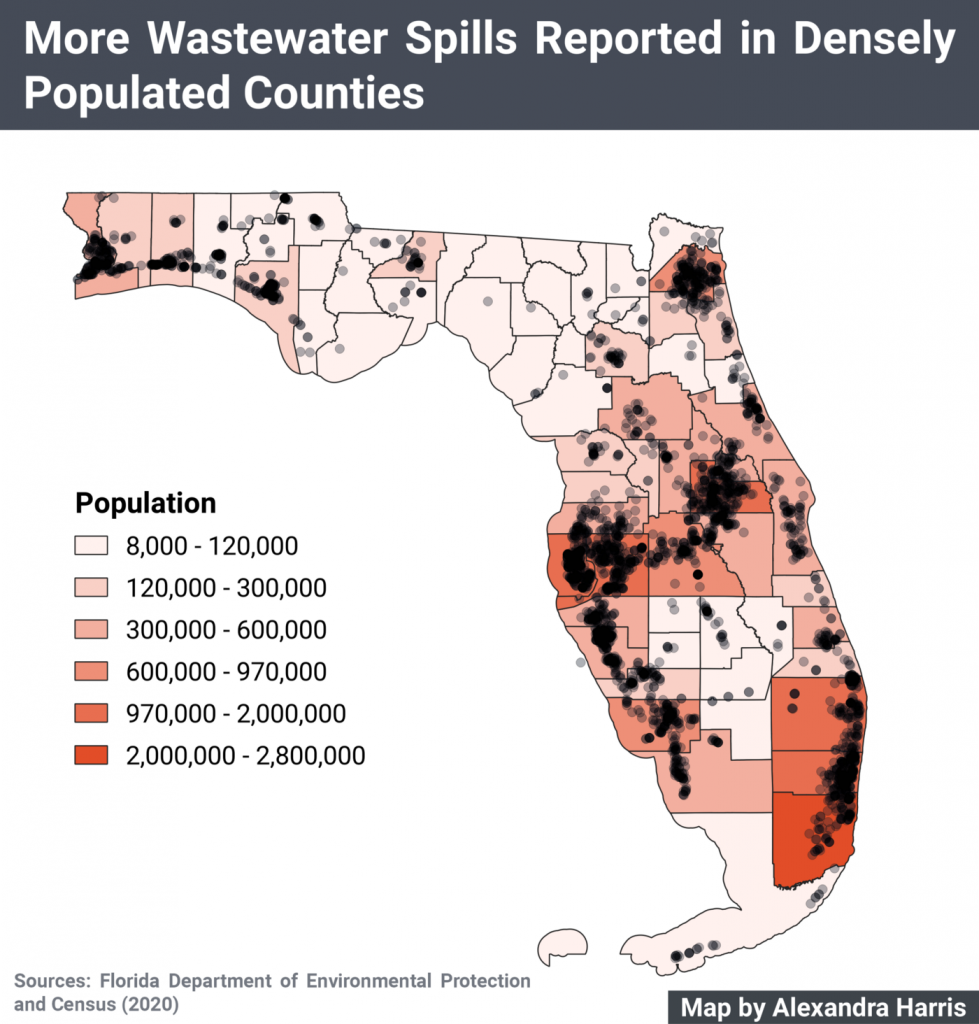

As the gallons of spills were tallied for counties across the state, central Florida emerged at the epicenter of the crisis

The spills ranged from treated to untreated wastewater. Untreated and partially treated sewage are the most harmful. Reclaimed water is wastewater cleaned for reuse purposes, such as agriculture and irrigation.

Untreated or partially treated spills contain raw sewage that carries bacteria, viruses and parasites, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. They may cause diseases ranging from mild stomach problems to life-threatening ailments like cholera.

Meanwhile, spills that enter waterways harm more than water quality and aquatic animals. When the water cannot be used for drinking; shellfish harvesting; or fishing or recreation, the losses reverberate through the economy.

While overflows occur in almost every sewer system, when they happen frequently, it means something is wrong, according to the EPA.

In Florida, the top causes reported for wastewater spills were systems inundated from rain and broken or failing equipment.

A century ago, sewage boats plied Florida’s waters to dump barrelsful of waste into the open sea. Some of the records for modern spills evoke that history.

In 2017, a caller reported and photographed raw sewage and toilet paper in a canal in Edgewater leading to the Intracoastal Waterway. Manatee sightings were replaced by the soiled tissues and human excrement.

The caller revealed that a sailboat owner was dumping the waste—almost a century since the days of the “Pocahontas” sewer boat.

Click the graphic below to explore WUFT’s interactive map of wastewater spills impacting Florida waterways.

The data indicated sewage spills caused fish kills in multiple waterways, ranging from Biscayne Bay to along the Intracoastal Waterway.

In the Florida Keys, dead fish, crab and lobsters were reported in a canal in 2018 — accompanied by a strong sewage odor.

“The water in the canal is brown,” the report stated.

Manatee River topped the chart for the most wastewater pollution reported over the years. The 36-mile-long river flows from Manatee County into the Gulf of Mexico and is home to wildlife that includes manatees, dolphins and alligators.

Others flock to the river for recreation, paddling kayaks and casting fishing lines along the tea-colored water.

The river is a cradle for threatened species like the wood stork. The bald-headed, three-foot tall bird is an indicator species, which serve as “excellent messengers of the past, present and future,” according to the National Park Service.

On a small island where the Manatee and Brandon rivers meet, the only wood stork colony in Manatee County finds refuge. The colony relies on the shallow marshes and puddles to catch fish, according to the Conservation Foundation of the Gulf Coast.

Climate change further threatens Florida’s crumbling sewage systems, with worsening heavy rains, storms and flooding. Historically, monthly totals for both spill volume and rainfall over the past two decades correlated strongly.

With climate change, one of the main threats to Florida is more occurrences of heavy rain, said state climatologist David Zierden.

Warmer air leads to more evaporation — and more precipitation. Heavy rains worsen the risk of flooding, which can strain aging infrastructure.

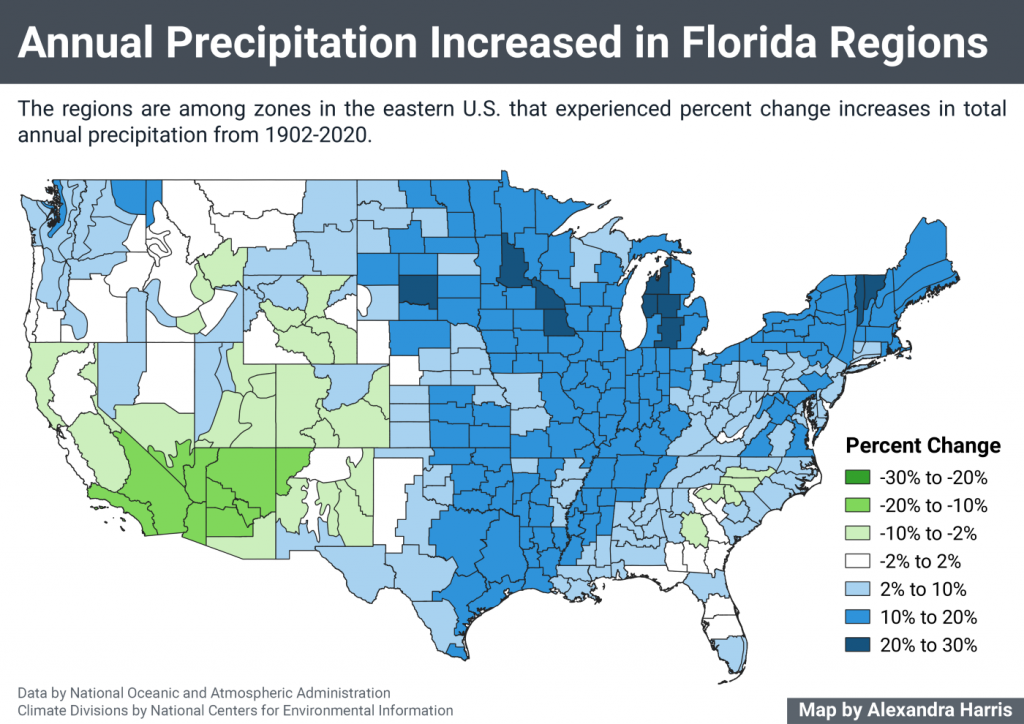

Annual rainfall has increased over the past three decades in the eastern U.S., Zierden said. In addition, Florida is seeing an increasing number of days with more than 3 inches of rain, he said, an extreme amount that can lead to flooding.

As hurricane season kicked off in Miami, the beginning of June brought heavy rainfall that caused sewer overflows and a no-swim advisory, according to the Miami-Dade Water and Sewer Department.

“It’s going to take a massive infrastructure overhaul to address it, especially if sea level rise accelerates as predicted,” Zierden said. “We’ve got a lot of catch up to do before we make it better.”

Meanwhile, the reported sewage spills concentrate in densely populated areas, which can impact a greater number of residents when the system fails.

Hundreds of people were left without drinking water in Sumter County in 2015 when multiple wastewater lines broke, according to the data. Other reports indicated raw sewage flowed through the homes and garages of Florida residents.

Florida’s population is projected to grow by more than 12 million people over the next half century, according to data from the Bureau of Economic and Business Research, projected out by the Florida Department of Transportation.

Among the state’s counties on track to gain the most people were ones already facing the biggest sewage spill crises.

In 2020, Florida took a historic step to protect water quality, said Alexandra Kuchta, press secretary for the Florida Department of Environmental Protection.

The implementation of the Florida’s Clean Waterways Act approved by Gov. Ron DeSantis is working to address the issue of aging infrastructure across the state, Kuchta said.

For the first time ever, she said the legislation requires power outage plans that aim to minimize untreated spills from all sewage disposal facilities. Septic tanks are now regulated as a source of nutrients. Fertilizer use must be documented to ensure compliance with Best Management Practices and to aid in evaluation of their effectiveness. The legislation also updated stormwater rules and design criteria to improve performance of the systems statewide and address nutrients.

Sewage disposal plants must now turn over financial records to DEP to prove funds are being allocated to infrastructure upgrades, repairs and maintenance to prevent systems from falling into states of disrepair, Kuchta said.

Additional legislation upped the fines for environmental crimes to hold polluters accountable, she said, which increased sanitary sewer overflow fines by 100% and all other environmental fines by 50%.

But the efforts leave the worsening root of the sewage crisis unaddressed. To slow the worst effects of climate change, Zierden said greenhouse gas emissions must be greatly cut.

“Our current governor and his latest budget has seemed to do a lot on the adaptation side, but we’re still hearing crickets on the mitigation side — actually cutting greenhouse gas emissions,” Zierden said. “We have to do both.”

Because a certain amount of climate change is locked in and will continue, adaptation is key, he said.

“But that’s only one piece of the puzzle,” Zierden said.

Meanwhile, President Joe Biden signed the bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act in 2021, which allocated an expected $19.1 billion to Florida with projects that include protection against extreme weather events. The plan also outlines mitigation efforts with funds to expand public transportation and electric vehicle chargers to address the climate crisis.

WUFT compiled a searchable table below for readers to locate spill information for their county and local waterways.

In the event of a discharge, Kuchta said DEP responds with a three-pronged approach:

(1) work with the facility to identify any releases and ensure the release is stopped as quickly as possible to minimize impacts to the environment and public health;

(2) gather and analyze information surrounding the circumstances of the reported incident(s) to evaluate it from a regulatory perspective; and

(3) identify any further corrective actions needed, including solutions to avoid future discharges and possible enforcement.

DEP also works with local health agencies to ensure that appropriate public health warnings are issued immediately. Kutcha said DEP’s primary compliance efforts are to prevent spills by ensuring facilities are properly constructed, operated and maintained.

About the project and reporting:

In 2000, the Florida Department of Environmental Protection began maintaining this formatted data on all unauthorized wastewater discharges reported in Florida.

WUFT filed a public records request for the data spanning more than two decades. The data arrived in multiple spreadsheets with errors and inconsistent reporting methods over the years.

While the data mistakenly included paint spills, other times it left fields blank for wastewater spills that amounted to millions of gallons.

This project was an effort to reveal the dirty water hidden among poor data.

For more detailed information on the spills, check the searchable table descriptions.

Contact Alexandra Harris at harrisalexmarie@gmail.com to provide updated information on any of the spills included in this project.

This story is part of the UF College of Journalism and Communications’ series WATERSHED, an investigation into statewide water quality marking the 50th anniversary of the Clean Water Act, supported by Pulitzer Center’s nationwide Connected Coastlines reporting initiative.

WATERSHED

WATERSHED