4 Days, 5 Murders

Episode 1: The Wall

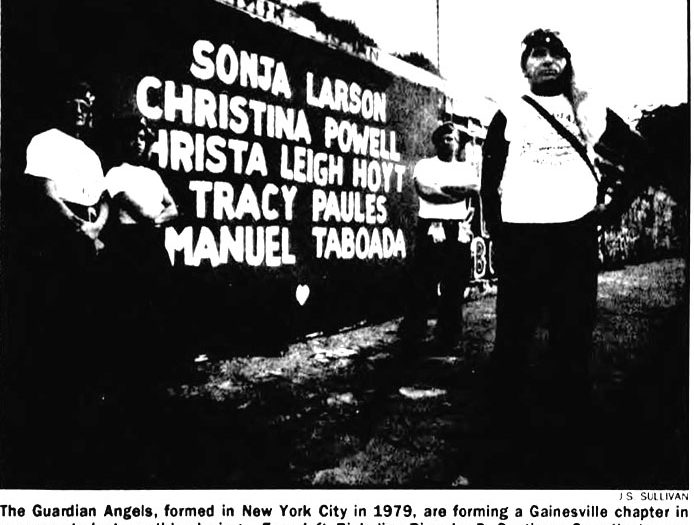

Two students are found murdered inside their Williamsburg Village apartment. Thirty years later, their names are still painted with three others on a memorial wall. Some would like to forget. Others say it’s important to remember.

A wall reminds Gainesville of the scars it will forever bear.

By Anthony Montalto and Anneliese Linder

A wall is generally built to divide. To keep people out of backyards or even from entering this country. In Gainesville, it does neither. Here, a wall serves to remind.

To remind because life is not just about the future. It is about the past. It is not just about anticipating but about remembering. No matter how painful that memory may be.

That’s why Paul Ortiz, director of the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program at the University of Florida, has dedicated his life to teaching history.

“I think, by all means, we need to remember,” says Ortiz. “And I think that’s one of the reasons why the wall space exists.”

That space is, of course, is the 1,100-foot long wall that runs along 34th Street, one of the busier arteries near campus. Originally built in 1979 to stave off erosion, it became a canvas for graffiti artists to showcase their art, a billboard for those who feel compelled to make public declarations: “Beat the ‘Noles.” Or a simple “Happy Birthday.” The panels change almost every day, with the exception of one.

That panel, now complemented with plaques on the trees in the road’s median, is reserved as “a sacred space of memory.” It’s a memory of a dark time when lives were lost in the cruelest of ways.

Gainesville does not make too many appearances in the annals of United States history. And yet, for a brief part of a typically sweltering summer three decades ago, this city skyrocketed to the top of newscasts and found its name splashed in headlines.

In the waning days of August 1990, as students segued from their last-hurrah revelries to the serious prospects of a new semester, a killer walked these small-town streets. Lurking. Stalking. And eventually, murdering in the most macabre fashion. Within four short days, five students who had come to this city with all the aspirations and dreams of youth were dead.

Their names are on that sole panel that is a constant on 34th Street: “Remember 1990. Sonja Larson. Christina Powell. Christa Hoyt. Manuel Taboada, Tracy Paules.”

The panel strikes a chord with longtime residents who have firsthand knowledge of that wretched time. They pique curiosity for others who were not even born then. Or moved here years later after time had eased the stinging freshness of tragedy. Others chose to forget as a way to ease the pain.

People found different ways to grieve, process and move on. Three decades is a long time and yet, for some, the murders will always be inextricably linked to Gainesville, a part of the city’s psyche that for better or worse will remain.

“It is something that I think, you know, we’ll just never get over,” says Pegeen Hanrahan, the former mayor of Gainesville who was starting her first year at graduate school when the killings occurred.

“I feel very inarticulate trying to explain it, but it definitely is a permanent, painful scar on the history of Gainesville,” she said.

Tonya Blazejowski, who knew Larson and Powell, appreciates the wall. It keeps alive the memories of the friends she lost.

“For it to be almost 30 years and for that wall to be upkept, I truly can’t tell you how much that means to me every single time I drive by it,” Blazejowski said.

Blazejowski takes her children to the memorial every anniversary to lay down flowers.

“When they were old enough to know, I told them. That way, I could point out the wall. That way, I could point out the palm trees. And I could just tell them you know, you know how special, you know, my relationship was, how down it really got me when this happened and how I was able to pick myself up through the grace of God and build myself back to become a nurse and a nurturer and someone to help other people grieve,” said Blazejowski.

Adam Tritt and Paul Chase painted the memorial on the wall shortly after the murders. The black, white and red paint is bold and striking but the colors were a spur-of-the-moment decision after the two friends argued over who would ride in the back seat of Tritt’s scooter to Walmart, where they paid about $11 for the paint.

“We just bought whatever paint they had leftover you know, ‘oops paint,’” Tritt recalled. “So that’s why we chose those colors, because they were cheap.”

The memorial, Tritt said, was meant to be temporary. But it became permanent and over the years, reporters have contacted him on the anniversaries of the murders to talk about his creation. The wall became a well-known memorial. He told a story about how his son found out about the Gainesville murders and the memorial his father painted in his Melbourne High School law class.

Eventually, the city designated the memorial panel a landmark. But Tritt believes it might be time for a change. The memorial, he wrote on his blog, is “perpetuating violence” and the victims and their families deserve better. Tritt has even offered several times to paint over it.

“No one knows what the hell it is. I mean, do they?” he asked. “Do people who didn’t live there at the time? Do new students know what it is?”

Perhaps some don’t. But trying to forget the past can lead to repression, said Ortiz, the historian.

“The human condition can consist of both moments of joy, but also sorrow and by cutting ourselves off from the sorrowful moments, we’re really disadvantaging ourselves.”

“The human condition can consist of both moments of joy, but also sorrow and by cutting ourselves off from the sorrowful moments, we’re really disadvantaging ourselves,” he said.

There are multiple ways to remember a tragedy and cope with the trauma in a healthy manner.

“I think especially in a university town, creating a space for dialogue, which is more than just rhetoric. It’s actually creating events where we allow people to come together give their thoughts,” Ortiz said.

Bernie Marrero, a health and rehab psychologist, had just moved to Gainesville a few weeks before the murders. He said emotional memories are hard to let go.

“The difficulty is that you can become so fixated on the memory of the trauma, that it continues to manifest itself, even in our sleep by way of nightmares and fixations and about the event,” he said.

Marrero’s friends questioned whether he should remain in his new city. But Marrero stayed.

“What we want to remember is what an incredible impact that this had on our community, the closeness, the support, the caring, the commemorative kinds of things,” he said. “So it was how we responded that we should be proud of. I will always celebrate having witnessed that in this community. And it reinforced even more so that this was the right place to live and raise my two daughters.”

Ortiz believes it is important for people to study history — and learn from it.

“It teaches us empathy,” he said.

Despite that, the murders tainted Gainesville’s name and forever associated this city with the crimes.

“It also followed us you know, so anywhere I would travel, people — one of those normal questions: ‘Hey, where are you from?’ and I say, ‘Gainesville, Florida,’ and immediately they associated us with those murders,” Mayor Lauren Poe said. “That was our calling card for a long time.”

Poe, a professor at Santa Fe College, said he has seen firsthand how the memories of the Gainesville murders have lived on.

“I teach teenagers and, and it’s something that most of them are familiar with — at least [the] ones that grew up around here, and so, I think that’s a testament to the endurance of the memory of those five individuals,” Poe said.

Hanrahan, the former mayor, said the murders left an enormous hole in Gainesville. The city, she said, will forever bear a scar. Whether there is a wall that serves as reminder, or not.

Special Report from WUFT News

Special Report from WUFT News