By Marlowe Starling

Raised along Miami’s Biscayne Bay, Marcelo Fernandes always had a favorite snorkeling spot, a 50-by-100-foot area where he could swim above coral reefs as recently as 2015. But a few years ago, he couldn’t find it. He must have lost the coordinates, he thought. Then it hit him: He did find his spot, but the corals had died.

Fernandes lives in a lush neighborhood called Bay Homes Park in south Coconut Grove, where tropical plants and flowers burst along narrow streets. Despite the upscale address, most of the homes rely on old septic tanks to get rid of sewage, which can leach into the bay during heavy rains that also flood the streets. Within the past four years, at least six of his neighbors have had to repair or replace damaged septic tanks.

The Bay Homes Park tanks are among an estimated 2.7 million sunk into Florida’s sandy soils. That’s nearly 13 percent of America’s septic tanks, the below-ground receptacles that dispose of a home’s sewage.

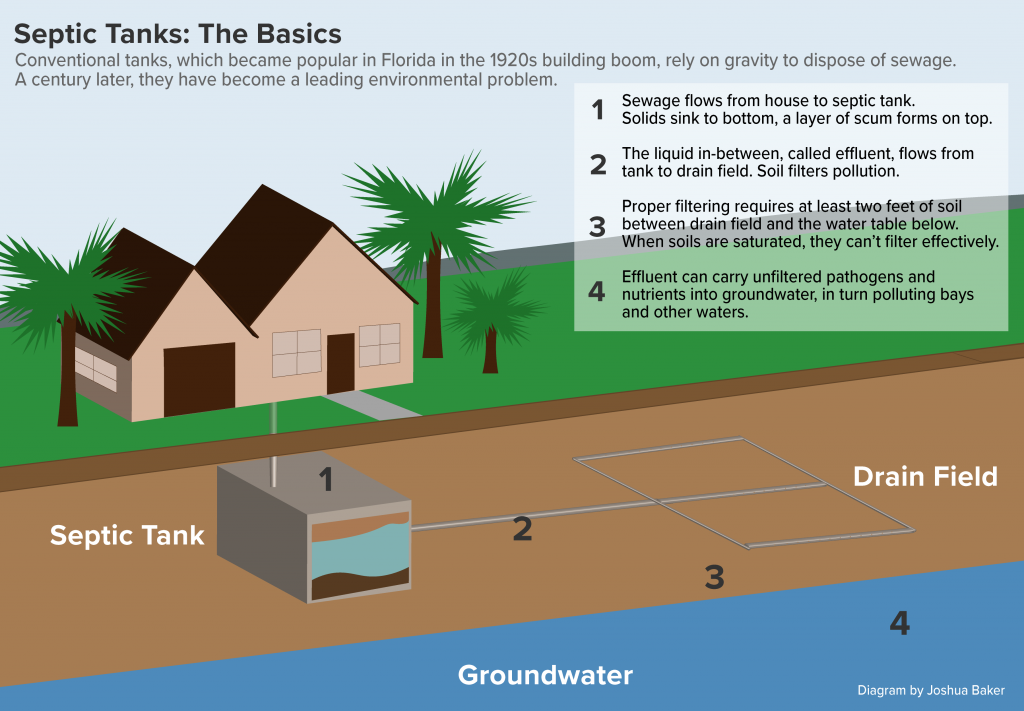

The simple systems seemed harmless in the 1950s, before Florida’s population grew to today’s 21 million. But leaky tanks spread pollution in a state pulsing with water. Scientists say that sea rise, storm-related flooding and other forces of climate change are aggravating the problems.

Less commonly known are the risks of aging, leaking septic systems to people. “It affects not just the ability to enjoy healthy coastal ecosystems and fisheries — but also human health,” said Florida Atlantic University research professor Brian LaPointe.

A Miami-Dade County report on the effects of sea rise on septic systems warns about the presence of viruses that can easily travel from the tanks to groundwater, the drinking water source for most Floridians.

Florida’s poor soils have less capacity for treating pathogens than those in other parts of the country, said Mary Lusk, a UF professor of soil and water sciences. Viruses are even smaller than bacteria, she said, making it easier for them to slip through soils.

“If (a virus) can live in the conditions of a septic tank, and it can make its way to water, then perhaps that can be a means of spreading that disease,” Lusk said.

Many viruses can’t survive the anaerobic conditions of a septic tank, she said. But it’s yet unknown whether a virus like COVID-19 — which scientists have found can make itself inactive — could survive those conditions and reach groundwater. COVID-19 has been found in untreated wastewater, according to the CDC, which advises that risk of transmission through properly maintained sewage systems is thought to be low.

Septic tank numbers rising

Properly maintained is the unknown — and why septic tanks have caused such collective damage to ecosystems.

“‘Working’ from the property owners’ perspective means the toilet flushes,” said Thomas Ruppert, a Florida Sea Grant coastal planning specialist.

That’s often far from the truth, he said. A submerged septic tank, or one that sits less than two feet above the water table, is a broken one. When gravity can’t carry the separated liquid, known as effluent, to the drain field below, nutrients and pathogens can contaminate waterways and groundwater.

Homeowners are ultimately responsible for paying to replace or repair a broken septic system.

“It’s sometimes a hard sell to homeowners, and rightfully so,” Lusk said. “You just have to realize if the system was put there 50 years ago, it probably isn’t quite up to speed today.”

People are also expected to pay a company to “pump” their system every three to five years to clean out the solids. Extension agents and others say that’s not always happening.

“I know people who proudly say, ‘I haven’t had my system pumped out in 20 years’,” said William Lester, a UF/IFAS Hernando County horticulture agent who is part of the state’s “After the Flush” educational program for homeowners and professionals.

“Yeah, well, that’s not really a good idea.”

Disease-causing microorganisms can pose risks to human health from old or poorly maintained tanks. Yet Florida’s environmental regulators don’t know precisely where every septic tank in the state lies, or how many may be compromised. Nearly 3 million have now been located, thanks in part to the Florida Department of Health’s 2014-2016 inventory project.

The map of known and likely septic tanks shows how central sewer – sewage pumped from a house to a local treatment plant via pipes – is concentrated in metropolitan areas. Rural areas that lack access to the pipelines often rely on septic tanks, which serve about 30 percent of Floridians.

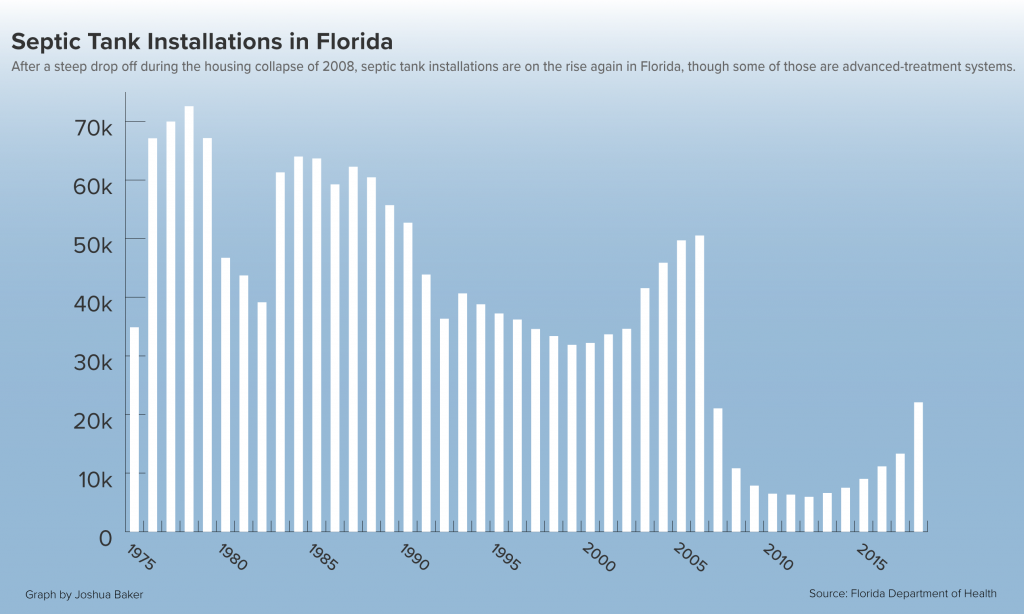

While septic tank installations declined for years, their numbers are on the rise again in Florida, according to an analysis by WUFT News. More than 22,000 were installed in 2018, compared with an average 8,502 new tanks a year over the decade prior, according to DOH data. Before 2008, the numbers were much higher, ranging from 21,000 to as many as 72,000 some years.

The recent installations likely include more-sustainable systems than those used in the past, said Roxanne Groover, executive director of the Florida Onsite Wastewater Association (FOWA).

The Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) launched a grant program to spur more homeowners to upgrade to nitrogen-reducing systems in nine springs-centered counties after the Florida Springs and Aquifer Protection Act of 2016. DEP grants pay licensed installers up to $10,000 to help homeowners upgrade to safer tanks.

DEP has funded just over 1,000 upgrades since 2018 at a cost of $10 million, according to the agency.

History of neglect

During the twentieth century, septic tanks were mostly out of sight, out of mind in Florida policy-making and legislation. Ecosystems in the fragile Florida Keys were some of the first to show the neglect. Canals filled with wastewater. Coral reefs declined. Two decades ago, the state ordered Monroe County to transition from septic to central sewer. LaPointe, who lives on Big Pine Key, said homeowners were responsible for $4,500 of the cost to abandon their tanks for the roughly $1 billion venture.

“We have really gone from an example of perhaps some of the worst wastewater treatment here in Monroe County to being now probably the best,” said LaPointe.

He said his local sewage treatment plant, Cudjoe Regional Wastewater, now removes about 98 percent of nitrogen from sewage. A traditional septic system removes only about 30 percent.

The Keys’ success is hard to scale in sprawling metros underlain with septic tanks, said Rachel Silverstein, executive director of the Miami Waterkeeper organization. A respective 107,000 and 50,000 tanks are in use in Miami-Dade and Broward counties, according to DOH data. Those that sit partially submerged in groundwater leech sewage that inevitably ends up in local waters.

Aggravated by the sea-rise and worsening hard rains of climate change, flooding is also a major driver of tank leaks and contamination. After Miami’s King Tide event of November 2016, high levels of fecal bacteria were found in floodwaters, according to the 2018 Miami-Dade report.

Such nutrient pollution is a major contributor to harmful algal blooms and seagrass losses of some 90 percent in Biscayne Bay, said Silverstein. Scientists worry the Bay has already reached a “tipping point” beyond which anything can be done to stop the damaging cycle of blooms.

:EPA recommends, but doesn’t require, “alternative systems” in areas with more permeable soil. The expense — either in transitioning to sewer like Monroe County or relying on homeowners to upgrade their own septic systems — is the barrier, said Silverstein.

“The projects annoy residents because they have to rip up roads, and then they put it back together and people are, like, what was six months of traffic for?” she said. “(They) don’t see any difference because it’s all underground.”

Slow-moving solutions

Florida lawmakers finally passed a septic tank bill with real teeth in 2010, requiring inspection every five years to ensure tanks work properly. But the law was repealed two years later under then-Governor Rick Scott after enormous backlash.

The 2016 springs bill created targets called Basin Management Action Plans (BMAPs) to reduce nitrogen levels in regions particularly vulnerable to groundwater contamination, all in North Florida.

Andrea Albertin, a biogeochemist who works on water-resources outreach for UF/IFAS in the Panhandle and leads that region’s “After the Flush” program, was among several scientists who said it’s simply too early to tell how effective the BMAPs are.

Regardless, that legislation left out 58 counties — including coastal swaths where septic tanks have proven devastating to the environment and risky to human health. Silverstein cited figures that more than half of Florida’s septic tanks are malfunctioning at least part of the year.

Even if septic systems effectively remove 99% of bacteria and protozoa, said Lusk, the UF soil science researcher, there’s still a chance the 1% can reach drinking-water wells.

“All it takes is one organism to get you sick,” Lusk said.

She predicts the next few years will bring a greater push to replace old and malfunctioning tanks. Other solutions include adding chlorine or UV radiation disinfection systems to new or existing tanks, according to Lusk’s research, which may be best for areas with poor soil. Both come with a cost: up to $2,000 for installation and up to $280 annually for operation.

At Bay Homes Park, Fernandes and his neighbors seek to pilot a new bioreactor sewage system and other solutions. Long-term plans include porous pavement to mitigate flooding and oyster beds in the Bay to filter pollutants. They are pending approval from the local commissioner, capital improvement department and city engineers.

Bioreactor systems add an advanced stage to conventional tank treatment. Beneath the drain field, an added layer of material such as woodchip or coconut fiber breaks down nitrates to nitrogen gas, Groover said, helping keep pollution out of waterways.

The coronavirus pandemic has postponed community meetings and progress, Fernandes said. But residents are committed to finding solutions as rains continue to flood the neighborhood.

This spring, the Legislature passed the Clean Waterways Act that will, among other water policies, transfer septic tank oversight from DOH to DEP. Pending Governor DeSantis’s signature, it takes effect July 1. Groover with the sewage association said the change will help the state focus on septic problems and help more homeowners with upgrade costs.

The Florida Springs Council, Sierra Club Florida and Waterkeepers Florida had a different response to the measure in a letter to Florida’s Chief Science Officer Thomas Frazer. Among other weaknesses, they wrote, the Act does not go far enough in adopting recommendations from the state’s Blue Green Algae Task Force, including “a septic system inspection and monitoring program” to identify and get rid of malfunctioning systems to “reduce nutrient pollution…and preserve human health.”

The bill does not restore the mandatory inspections lost a decade ago.

In Bay Homes Park, residents await the inevitable summer rain. “It’s not a rosy picture,” Fernandes said. “Even if we start now, we’re still going to lose a lot.”

The Human Hazard

The Human Hazard