Paradise for Mold

A lesser-known consequence of a warmer, wetter climate, mold is also a trigger for Florida’s most-common chronic childhood illness—asthma.

By Noura Al-Rajhi

Twenty-four to 48 hours. After a storm, that’s all it takes for mold to compromise a home or the health of the family living inside. From under the kitchen sink to ceiling tiles and insulation systems, mold begins in the most-hidden of places.

Mold growth is already a prevalent issue for Florida due to the state’s hot, wet and humid environment. The state is the most humid in the U.S. according to Florida Climatologist David F. Zierden, making it an ideal breeding ground.

Because molds are highly influenced by weather including heat, storms and extreme downpours, allergists, immunologists and other experts worry climate change could lead to increasing exposure, allergies and asthma. While the expanding pollen season and its impact on allergies is a well-known consequence of warming, expanding mold spores have been, well, hidden under the kitchen sink.

Mold growth is a particular problem for asthma, the most-common chronic childhood illness in Florida. About 10.5% of children aged 17 years or younger in the state have asthma, while the national average is 7.9%, according to a 2019 America’s Health Ranking report.

“Mold is one of several allergies that can affect asthma,” said Dr. G. Edward Stewart II, a board-certified allergy and immunology specialist who practices in Central Florida. People allergic to it have developed an antibody called Immunoglobulin E (IgE), which recognizes mold and binds up with it, setting off a chain reaction that inflames asthma, Stewart said.

Those patients can suffer asthma attacks and bronchospasms that constrict the airway, preventing them from breathing correctly. But mold can also lead to ongoing symptoms, which may be more challenging to manage, Stewart said.

Depending on the species, length of exposure, and severity of spread, mold can also cause respiratory illnesses in healthy people—a significant concern for healthy children, who are most susceptible to developing asthma.

A fungus among us

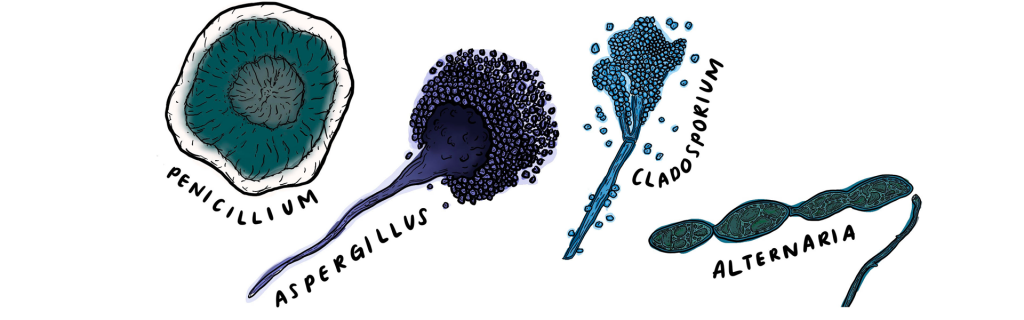

Mold is a type of fungus that proliferates by releasing spores, often toxic. The spores travel through air, so mold spreads easily. The mold digests organic materials such as wood, destroys it, then spreads to destroy the next material. Although there are hundreds of different species ranging from harmless to toxic, the most common that cause allergies are Alternaria, Aspergillus, Cladosporium and Penicillium.

A meta-analysis of 33 respiratory health studies found that excessive indoor dampness and resulting mold are a “potentially large public health problem” that can go unnoticed. The researchers, at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, found that “building dampness and mold are associated with approximately 30-50% increases in a variety of respiratory and asthma-related health outcomes.”

Abby Klein, president of the mold-removal company Miami Mold Specialist, says she sees a lot of mold growth in central air conditioning units, vent systems and homes that are not properly sealed. She compared an A/C’s function to that of a lung, pushing air through the entire system.

“If you have an issue in the AC unit you are going to eventually have it in the whole property because it is obviously spreading through the AC.”

So, preventing indoor mold in Florida takes a well-sealed home and well-functioning central AC. But that’s not often the reality for low-income and otherwise vulnerable families. While the vast majority of Floridians have A/C, that doesn’t mean it’s working properly. In some cases, people can’t afford the maintenance or electric bills.

Mold and the law

In others, a landlord hasn’t maintained the unit—or later, isn’t willing to get rid of the mold. A report by the World Allergy Organization on the impact of climate change on asthma and allergic disorders cited the prevalence of “damp indoor problems” in low-income communities substantially higher than average.

Matthew Militzok, a mold litigation attorney based in South Florida, said a large percentage of people who come to him with claims are low-income renters dealing with mold. Some are living in substandard conditions with minimum or no resiliency to mold. The law needs strengthening to better protect them, he said.

“Florida does not have a very strong tenant protection statute when it comes to mold exposure under the Florida Landlord-Tenant Act,” Militzok said.

That Act is Florida Statute 83. Chapter 51 covers a landlord’s obligation to maintain a rental; landlords are legally bound to provide tenants with a livable environment. Militzok said tenants dealing with mold can either withhold rent payments, claiming the mold has made their unit inhabitable, or deduct the cost of mitigation from their rent.

However, he said not many people know how to claim those rights. “In Florida the tenant does not have any rights under the landlord tenant act until unless the tenant prepares and serves a seven-day notice to cure the defects in the property and delivers it to the landlord,” Militzok said.

The notice must have certain statutory language. Without that, the tenant has not “activated” rights, thus making the claim ineffective in court, Militzok said.

Militzok said he hopes to see the Legislature not only strengthen tenant protection, but support outreach programs that make it easier to find support. California in 2016 enacted a new mold law that considers mold a condition of substandard housing, meaning renters can report it to a local jurisdiction to demand repairs and fine landlords.

Some landlords “are very restrained when it comes to making repairs and maintenance,” Militzok said. “So, they will do the bare minimum or in some cases they won’t do anything.”

Confronting childhood asthma

Mold is particularly worrisome for childhood asthma; scientists have found statistically significant correlations between molds in the home in infancy and asthma risk at age seven.

Asthma rates have increased dramatically in Florida over the past thirty years among all populations, with a disproportionate impact to minority and low-income Floridians, according to the Florida Asthma Coalition. More than half a million children and two million adults are diagnosed, making asthma is one of Florida’s major public health priorities.

The state is working on the problem at multiple levels including the Florida Asthma Plan, a five-year strategic plan with guidance and direction for healthcare, public health, school and other professionals.

Asthma doesn’t have a cure, but it can be controlled, and education helps: Kids whose asthma is controlled sleep better, don’t miss as much school, can play sports, and make fewer visits to the ER. Guided by the state’s Asthma Plan, the Asthma Coalition targets schools, childcare providers, health plans, hospitals, doctors and pharmacies to improve families’ knowledge and asthma control. A home-visitation team checks in on families and walks through areas where the child spends most of their time to check for all possible asthma triggers.

But ultimately, Florida must also address the rise of those triggers—from mold to increasing pollen counts to air pollution, said Melissa Baldwin, program manager for Florida Clinicians for Climate Action, a coalition of doctors and other health professionals who are concerned about the impacts of climate change on Floridians, especially those in vulnerable populations

“If we do nothing to reduce heat-trapping pollution, these health harms will only increase,” said Baldwin.

“The good news is that the actions we take to improve our climate will benefit our health.”

The Human Hazard

The Human Hazard