How Harmful to Humans?

Harmful algal blooms have long been known to plague Florida’s waters and cause temporary illness in people. Are they also linked to longer-term diseases?

By Zahra Khan

In late morning, peak beach time for visitors to Captiva Island, the only bodies stretched out on the sand were lifeless. Hundreds of silver corpses rotted in the sun. Worse was the smell, gut-wrenching, eye-watering and nose-plugging. In the calm bay between Captiva and Sanibel in southwest Florida, white trout bellies floated. Upside baitfish, catfish and small sharks crowded the gentle waves as they slapped onto shore.

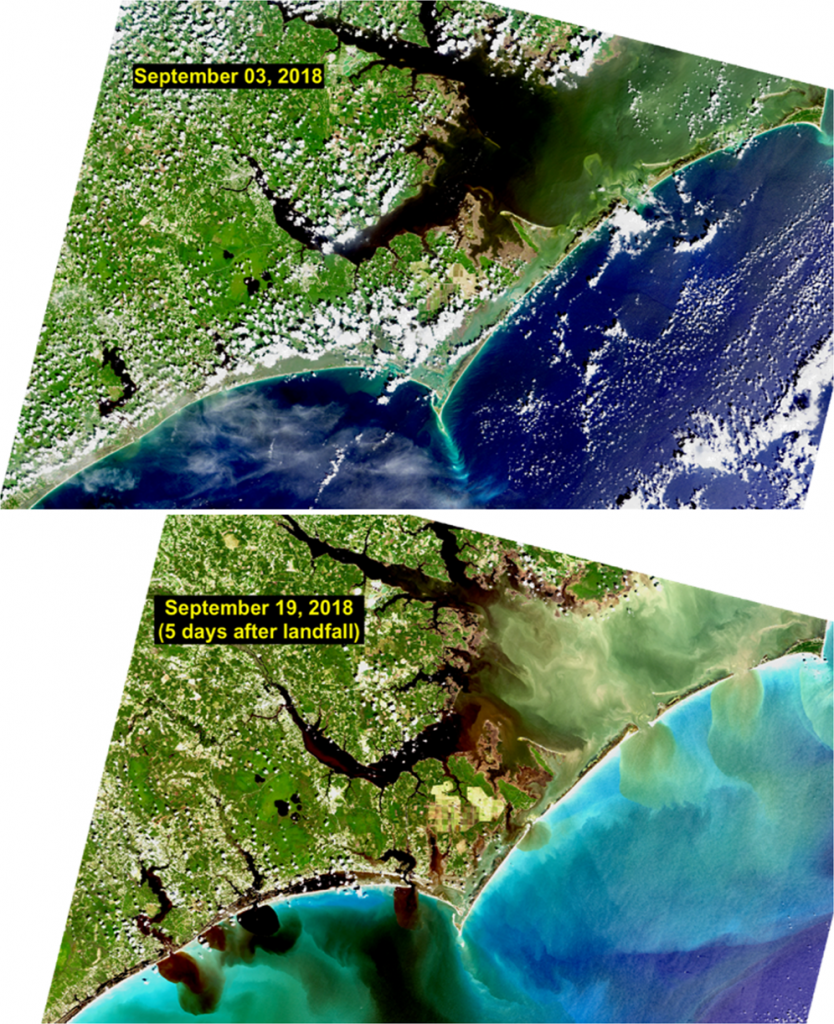

Caused by harmful algal blooms (HABs), such scenes are not new; instances of “red tide” and fish kills were documented by Spanish explorers in the 1600s. But large-scale outbreaks of red tide in the ocean and blue-green algae in freshwaters in recent years—like the 2018 crisis on beloved beaches like Sanibel and Captiva—have brought many more Floridians nose-to-nose with the blooms.

Leading harmful-algae researchers such as Hans Paerl at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill’s Institute of Marine Sciences say part of the trouble is the warming world. While high-nutrient waters are primary drivers, “blooms like it hot,” Paerl said during a keynote speech at UF’s Water Institute Symposium this spring. More-extreme rains and hurricanes also can aggravate the blooms in estuaries and other waters, his research has found.

Blue-green algae, called cyanobacteria, bloom where waters have high concentrations of nutrients—in particular, nitrogen and phosphorus. In Lake Okeechobee and extending out the St. Lucie and Caloosahatchee rivers, those nutrients wash into the water from farms, leaky septic tanks and fertilizer runoff from yards.

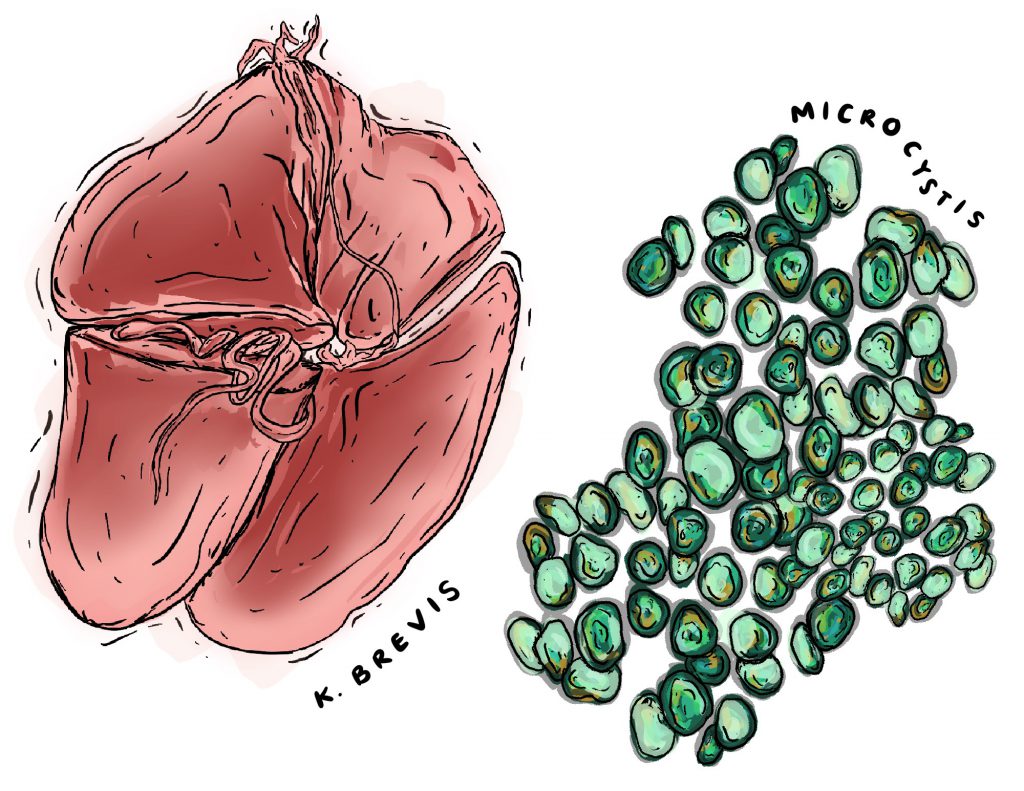

When they reach saltwater, blue-green algae can intensify the red tide—and the public health calamity for humans and animals. Red tide releases brevetoxins that cause temporary ailments such as severe respiratory irritation and asthmatic symptoms. Filter-feeding organisms such as clams and oysters can also absorb the toxins; consuming them could lead to neurotoxic shellfish poisoning, according to the Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium in Sarasota.

But as harmful algae blooms expand in Florida and around the world, scientists are researching additional possible health impacts from their toxins, which include cyanotoxins, microcystins and a neurotoxin known as BMAA, short for β-methylamino-L-alanine.

Microcystins can cause liver damage in otters, birds and pet dogs, said Ruth Francis-Floyd, director of the Aquatic Animal Health Program in UF’s College of Veterinary Medicine. However, lack of commercially available testing means the cases often go unreported—or unknown.

“My guess is that most (animal) cases are undiagnosed,” said Francis-Floyd.

Dogs that frequent HAB-contaminated freshwaters with their owners and die after ingesting toxic algae often go unreported as well, she said.

Among aquatic animals, microcystins persist in the food web and appear to cause neurological problems in dolphins off the coast of Florida that have stranded. Though the cause of the strandings isn’t certain, the types of lesions found in the dolphins are consistent with those found in humans with neurodegenerative diseases, Francis-Floyd said.

HAB toxins have likewise been associated with neurodegenerative diseases in people, including ALS, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, though scientists say they need considerably more research to determine any cause-and-effect.

Researchers at UF’s College of Medicine in January embarked on a large-scale epidemiological study on the link between freshwater algal blooms and human diseases in Florida, said Yi Guo, an assistant professor in the Department of Health Outcomes & Biomedical Informatics. Florida Atlantic University, the University of Miami and Florida Gulf Coast university are also part of the research award from the Florida Department of Health to examine different facets of harmful algae’s risk to people.

In the UF study, Florida LAKEWATCH is testing for harmful-algae hotspots around Florida. Medical researchers are comparing the hotspots with those for neurological diseases, using a database of nearly 15 million electronic records.

While the water testing has been ongoing during the coronavirus emergency, Guo said the pandemic has held up the lab portion of the research. The team has requested an extension from the Department of Health.

While the extent of human health risk remains uncertain, scientists who study harmful algae blooms say they are becoming one of the greatest threats to water quality—at least during times of outbreak.

At the UF Water Institute symposium, Bryan Brooks, Director of the Environmental Health Science Program at Baylor University, cited large-scale reported illnesses in Utah and California from toxic algae. Other human health impacts may be less-obvious now but emerge in the future, said Brooks, also Editor-in-Chief of Environmental Science and Technology Letters.

“To say that I’m not concerned that populations that are consuming water from reservoirs in different places across the country that may be contaminated with microcystins and fatty liver disease developing in the next decade or two,” Brooks said, “would be a lie.”

The Human Hazard

The Human Hazard