Florida Gators football fans need only take a few steps to find relief from soaring stadium temperatures. Chilly misting stations, free all-you-can-drink ice water and specially designed air-conditioned “cooling buses” are available during the hottest home games at Ben Hill Griffin Stadium. Athletic officials note that heat-related problems are a real danger and a common predicament on game days.

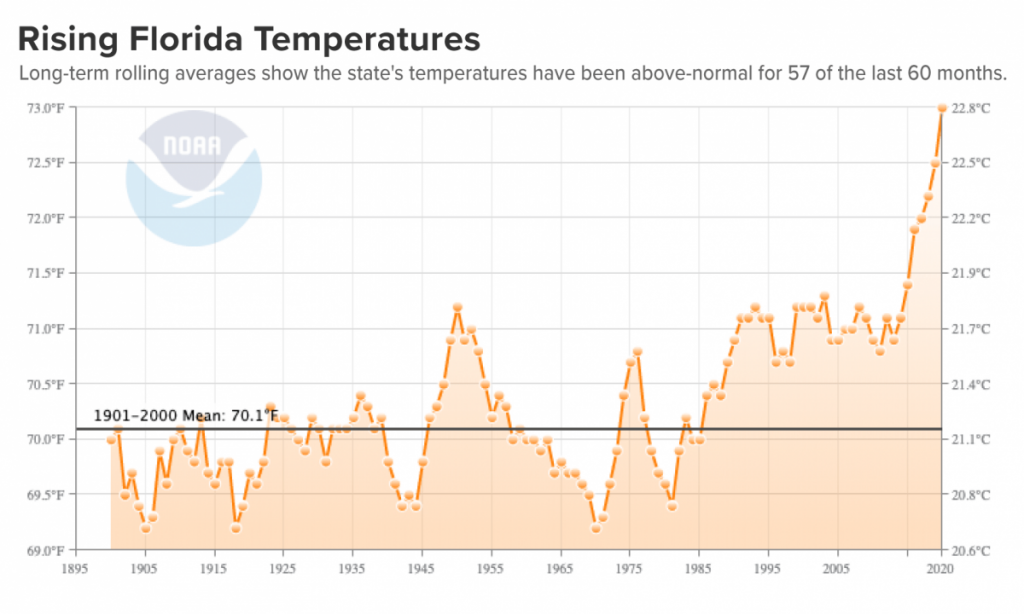

Florida shattered heat records this spring when statewide average temperatures measured a dramatic 7.1 degrees above normal for March, according to state climatologist David Zierden at the Florida Climate Center in Tallahassee. Miami hit 97 degrees last month, an all-time record for April. Statewide, averages have been higher than normal for 57 out of the last 60 months, said Zierden, who worries about hotter times ahead.

The state is among many identified across the U.S. for dangerously hot days as global average temperatures rise with the changing climate. Several of those states are innovating ways to help residents beat the heat. But while Florida has gotten good at keeping sports fans, theme-park goers and even cattle cool, policies for vulnerable populations—such as the elderly, outdoor workers and the incarcerated—lag behind.

A study by the Union of Concerned Scientists forecasts that with no reduction in the global carbon emissions leading to warming, Florida by 2050 would see “in an average year and averaged across the state, 105 days with a heat index over 100°F (up from just 25 days historically) and 63 days with a heat index over 105°F.”

Those kinds of temperatures would mean trouble for Floridians, especially if combined with other natural disasters like hurricanes that knock out electricity, the study says.

“Most buildings in Florida already have air conditioning, so it’s really about the power,” said Craig Fugate, former FEMA administrator during the Obama administration and director of the Florida Division of Emergency Management from 2001-2009.

But for vulnerable populations in Florida, it’s not always possible to turn down the thermostat.

Behind bars in the “hot box”

The Florida Department of Corrections incarcerates approximately 94,000 inmates. But only 18 of its 50 prisons are equipped with air conditioning in most housing areas.

“New institutions are designed with air conditioning, but many current FDC facilities were constructed prior to air-conditioning being commonplace and were designed to facilitate airflow to provide cooling,” FDC officials said in a statement. “Renovations to include air conditioning would be prohibitively expensive in older buildings not designed for modern cooling systems.”

State Rep. Dianne Hart, D-Tampa, has visited 55 private and public prisons in Florida and said she experienced firsthand the extreme temperatures throughout.

“It’s extremely hot inside of our facilities,” Hart said. “I am pouring in sweat as I stand in the facilities to talk to the inmates.”

FDC reports that every institution includes at least some sort of climate control such as fans or exhaust systems. But Hart said fans may often be ineffective as they merely circulate hot air.

Hart visited the pregnant inmate dorm in Lowell Correctional Institution north of Ocala last summer, where she said temperatures soared in excess of 100 degrees. The air conditioning unit was broken and had been for an extended period. Prison officials fixed it within a week of her unannounced visit, she said.

“We’ve been assured that will never happen again with our pregnant women,” Hart said. “Imagine the kind of heat they were under.”

Hart said heat in the prisons “wears you out and makes you tired” and said her and her staff’s clothes and hair were sticking to their bodies and faces after only an hour-long visit.

“When I come away feeling tired and frustrated that I’ve been in this hot box, I can’t imagine what it does to the psyche of a person that’s in that every single day, day in and day out,” she said, adding she worries about heat making people more susceptible to violence or aggression.

The FDC said in a statement that “Housing units for the most vulnerable inmate populations such as the infirmed, mentally ill and geriatric are also air-conditioned.”

It added that general population inmates who do not live in air-conditioned dorms have access to A/C in other buildings used for chapel, programs and administration, and all housing units contain refrigerated water fountains.

Hart said that she hopes the Legislature will start investing in A/C for prisons as part of an effort to improve living conditions for incarcerated people overall.

Hot work under hot sun

While some can crack jokes at the water cooler and work in air-conditioned offices, farm, construction and landscaping workers might spend the entire day laboring in the sun. That makes them among the most susceptible to heat illness.

A 2018 study from Public Citizen and the Farmworker Association of Florida found that “over four in five workers had core temperatures that exceeded 38°C (100.4°F) on at least one of the study days. This temperature is the recommended physiologic limit for core temperature, at which the risk of serious heat injury rises steeply for many individuals.”

Workers in the study also frequently reported heat-related illness symptoms in the course of the workday, and many were found to be severely dehydrated, which is tied to kidney ailments.

When agricultural workers head home from the fields, their living conditions also may not be cool enough. Air conditioning is not required in migrant housing, according to Florida Administrative Code.

Antonio Tovar, the general coordinator for the Farmworker Association of Florida, said that while cooling conditions tended to be acceptable, he estimated that 10% of workers in the study did not have air conditioning in their housing.

Lack of cooling is also a problem on the buses and other transportation that take workers to the fields, Tovar said. A farm worker died in 2016 after complaining of heat exhaustion on a bus heading back from tomato fields.

“Most of them (buses) don’t have A/C,” Tovar said. “At the end of the day, when most of the workers are already dehydrated, it’s an issue.”

Tovar said he hopes to see Florida follow in the footsteps of California, which requires employers to ensure that outdoor workers have access to rest, water and shade when temperatures reach a certain point. Florida lawmakers proposed just such a “Heat Illness Prevention” bill in this year’s legislative session. It died in the Senate Agriculture Committee.

Cool solutions

When Hurricane Irma tore through peninsular Florida in September 2017, it also cut power to about two-thirds of the state’s utility customers, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Outages dragged on for some for more than a week. That month, “well-above average temperatures” also plagued parts of central and South Florida, with several stations in the state hitting heat records, according to the National Centers for Environmental Information.

The disaster underscored the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s conclusion that air conditioning is “the number-one protective factor against extreme heat, which is an essential health resource for vulnerable populations.”

After a Hollywood nursing home lost power and A/C in Irma, a dozen residents died of heat illness. Former Florida Gov. Rick Scott was prompted to require emergency generators in all assisted living facilities and nursing homes. Yet reports show many nursing homes are still without power backups that could keep the A/C running during outages—even as the elderly are among the groups most susceptible to heat-related illness and death.

In the wake of the storm, some Florida counties opened air-conditioned cooling centers so citizens could get some relief. Pinellas County opened up 30 cooling facilities across the county, announcing the locations on Facebook.

Jessica Geib, emergency disaster preparedness manager for Pinellas County Human Services, said officials rented portable A/C units from a private company, something the county would be prepared to do again “in any sort of significant power outage, specifically in the summer months.”

But for Floridians without A/C, extreme heat is an emergency even when the power is on. The American Housing Survey reports that almost all Florida homes have A/C. That doesn’t account for anyone who has a broken unit or can’t pay the bills.

Internal medicine specialist Dr. Cheryl Holder at the Florida International University Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine in Miami tells a story of an older African American patient without the means to run her A/C. Yet living in a high-crime area, the patient was afraid to open her windows even in “a bout of stifling heat and humidity.”

Some parts of the country have established regular summer cooling programs for residents lacking A/C. San Diego County’s Aging & Independence Services division opens up more than 115 “cool zones” in summer months. “Cool Zone sites offer an alternative where those without A/C or those for whom it would be prohibitively expensive,” Sarah Jackson, communications manager for the division, wrote in an email.

The statewide “Keep Cool Illinois” program features an interactive website, allowing users to search by ZIP code to find the nearest cooling centers, open through the summer months.

Hotter up north

While Miami has made headlines this month for the earliest hot temperatures in history, the northern reaches of the state are actually the most vulnerable to extreme heat, according to Peter Waylen, a professor of geography at the University of Florida who researches heat.

This is because the ocean moderates Florida’s temperatures, he said. Water heats and cools more slowly than land, keeping temperatures on the coast and down south more stable and less extreme compared with places farther from water, such as inland and northern counties.

Florida is one of 16 states and two cities in the CDC’s Building Resilience Against Climate Effects (BRACE) program developing strategies for the health impacts of climate change including extreme heat. FL BRACE is primarily focused on supporting local public-health interventions and evaluating their impact, according to researcher Christopher Uejio in Florida State University’s Department of Geography. For example, a mini-grant funded Volusia County’s “Beat the Heat” campaign that targeted vulnerable populations through social media, back-to-school events, business partnerships and a website. Organizers reported promising results, but said local health offices would need funding and other support to be able to expand such efforts.

So far, the FL BRACE pilots have not been scaled up. At the state level, Florida’s Hazard Mitigation Plan goes into detail on how dangerous Florida’s heat can be but does not elaborate on solutions or responses as it does for other emergencies. The plan’s maps show some of Florida’s rural northern counties are among the most vulnerable, though local officials say heat is not a big priority, especially given other needs.

“It’s hot every daggone day,” said Dan Mann, public information officer for the Florida Department of Health (DOH) in Bradford County.

Kelly King, public information officer for DOH in Calhoun County, likewise said extreme heat was not a big concern for residents — though the town of Blountstown is trying to raise funds for a new splash pad to cool people off.

Another bill that failed during this year’s legislative session would have required an annual climate health planning report to keep Florida lawmakers and the governor aware of emerging threats. Fugate said attention to the need to mitigate heat might become more focused as temperatures rise and the state continues to adjust to the changing climate.

“The climate is changing faster than much of our systems, the built environment and societal systems can adapt,” Fugate said. “In the last couple of years, I think there’s a growing consensus that the climate impacts that people are forecasting are no longer decades away. They are occurring now.”

The Human Hazard

The Human Hazard