Major spills from Florida’s sewage treatment plants are on the rise—and so are the storms that can cause aging pipes to burst

By Everitt Rosen

When they emerged from their homes after Hurricane Irma, many Floridians were dismayed to find stinking waters in streets and canals along with the customary down trees and powerlines. The storm swamped cities across the state in more than 88 million gallons of sewage.

Irma’s powerful winds and heavy rains knocked out power to pumps and other equipment utilities use to prevent wastewater lift stations from backing up, unleashing a miasma of waste into neighborhoods from Miami to Jacksonville.

Foul concoctions seeping from manholes forced utilities to relieve sewer pressure by spilling wastewater into nearby water bodies. Waste flowed into Miami’s Biscayne Bay, Tampa Bay, southeast Florida’s Indian River Lagoon, into streets and creeks in Fort Myers, into the St. Johns River in Jacksonville and many other beloved waterways.

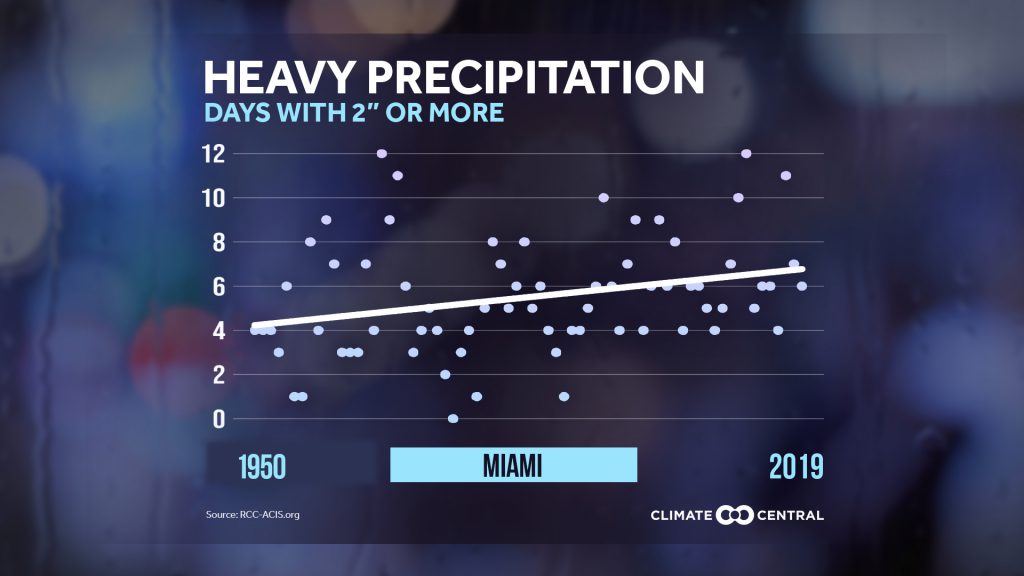

Three years later, it has become clear that those spills were not a fleeting hurricane emergency, but a new reality as aging infrastructure comes up against sea-rise and extreme rains associated with warming. Data from the Florida Department of Environmental Protection show the number of sewage spills in the state has risen steadily over the past decade.

Fort Lauderdale this winter and spring endured the worst state sewage spills in Florida history. Crumbling sewer pipes built half a century ago burst repeatedly, sending more than 200 million gallons of sewage into streets, yards and waterways.

“Fort Lauderdale is the poster child for this problem,” said Brian LaPointe, a research professor at Florida Atlantic University’s Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute.

While centralized wastewater plants are considered the safer solution than septic tanks to treating the waste of 20 million Floridians and 130 million annual tourists, systems built mid-20th century were not designed to deal with that number of people—or this century’s weather extremes.

“Because of climate change, you now have flooding in localized areas that wasn’t typically planned for and with these pipes,” said Marilu Flores, regional manager for the Surfrider Foundation in Florida and Puerto Rico. “With these systems being so old, now having to contend with rising sea level a lot of times straight out the sewage grates, you do now see and smell raw sewage.”

In 2019, the Department of Environmental Protection reported 2,779 wastewater spills in Florida, compared with 1,282 reported spills in 2007. There was a large jump in 2017, the year of Hurricane Irma, of a reported 3,452 wastewater spills.

The data show that about a quarter of the billion gallons of wastewater that have spilled into Florida’s waterways in the past decade was raw sewage. Wastewater is all used water, and sewage is the part that flows from toilets.

Nasty smells are the least of the worries. Experts and people who recreate in Florida’s waters say the spills are a worsening public health threat. Wastewater contains several types of disease-causing pathogens including bacteria, parasites, fungi and viruses. COVID-19 has been found in untreated wastewater, according to the CDC, though researchers do not know whether the virus can spread to a person exposed to a sewage spill. The agency advises that “the risk of transmission through properly designed and maintained sewerage systems is thought to be low.”

Pathogens in wastewater are known to cause lung and intestinal infections. Bacteria like E. coli and salmonella can cause fever, diarrhea and sometimes other symptoms like vomiting. Sewage spills can carry yet more dangerous bacteria including Salmonella enterica and Vibrio cholera, which cause typhoid fever and cholera.

When spilled sewage mixes with stormwater and stands in houses or in streets, either from thunderstorms or more-severe events like tropical storms and hurricanes, it can cause unmanageable infections for those who come in contact with the water. A study by the University of South Florida found bacteria in wastewater that is resistant to vancomycin, a common last-resort antibiotic.

Fungi can lead to severe allergic reactions and worsen asthma. Roundworms and other parasites are sometimes hard to detect due to their symptoms, which can seem like a common cold or constipation. Enterococcus, typically present in the gut, can cause grave infections if they spread to other parts of the body through the environment.

“Enterococcus bacteria can cause serious issues to people who may have a cut they’re not aware of or that they thought had healed. In very extreme cases it can lead folks to losing appendages or things like that,” said Flores with Surfrider. “If you have underlying health conditions, if you are immunocompromised, the sky’s the limit on how some of this bacteria can affect you.”

The spills also lead to widespread public health threats such as harmful algal blooms.

Solving Spills

Florida follows a three-pronged response in the event of a sewage spill, said Dee Ann Miller of the state’s Department of Environmental Protection. Utilities must report releases immediately, and DEP works with them to stop a spill as quickly as possible. The agency investigates to determine if violations and penalties are in order, and also identifies possible solutions to avoid future discharges.

The state also has an emergency response system that includes “utilities helping utilities” to stop spills during hurricanes and other disasters.

Preventive measures can include sending min-cameras down manholes to check for leaks and cracks in pipes, said Nick Sortal, a Plantation City Council member who has focused on preparation “in case we mimic New Orleans (Katrina), Houston (Hurricane Harvey)” or other epic hurricanes.

“It’s almost like a colonoscopy,” Sortal said. “You could be preventative and stop it from being a total disaster.”

But ultimately, Florida’s communities must invest billions statewide to upgrade failing sewage systems. Fort Lauderdale is proceeding with a $65 million project to install nearly 50,000 feet of sewage pipe the diameter of a table-top to stop spills.

Sortal said because they are out of sight, fixing the underground pipes is a hard sell to taxpayers, compared with investments in amenities such as parks. But now that obvious sewage spills are revealing the troubles underground, citizens and business people will insist on it. “There is nothing worse for real estate than to try to sell a house where you walk outside in the backyard and it smells like poop,” Sortal said. “You can’t do it.”

This spring, the Florida Legislature passed the Clean Waterways Act that will, among other water policies, hike fines against utilities that spill sewage, and require annual reports to the governor and lawmakers on all such spills. The bill also requires new ordinances to manage stormwater including what is known as green infrastructure—wetlands and other natural areas restored to absorb floodwaters and help clean up pollution.

But Flores of Surfrider said ultimately, the combination of aging sewage infrastructure and climate change will mean managed retreat for some places—the relocation of people and buildings out of the riskiest areas.

“What communities really should be focusing on is getting their elected officials to buy back public-use lands, turn them into parks, replant mangroves, work on existing sewage infrastructure and get people out of those homes,” said Flores.

“At the end of the day, you’re one catastrophe away from losing it all.”

The Human Hazard

The Human Hazard