A hurricane’s unseen effects on families

April 8, 2019

Like many native Floridians, Nichole Dawson knows how to prepare for a hurricane.

She digs for extra batteries and flashlights, stocks up on cases of water and leaves the Weather Channel running nonstop in the background.

When Hurricane Michael approached, the 33-year-old mother of three, along with her husband Spenser, readied as best they could. But, neither was prepared for the aftermath.

Their 3-year-old daughter Marleena, who they call Marlee, now screams when she sees the tips of her fingers wrinkle in the bathtub. Meanwhile, their son, Jonathan Yates, 14, is lying to his teachers. Nichole and Spenser fight now more than ever before, but they don’t want their kids to hear the anger and so they bicker behind closed doors.

It’s too late. They know. The toll of a hurricane impacts families like the Dawsons long after the debris is cleared.

Debris from Port St. Joe homes filled the roadsides of the town’s residential areas for weeks following the passage of Hurricane Michael on Oct. 11.Damaged homes. Shuttered schools and businesses. Downed trees. Blocked roads. They are the wretched reality in the aftermath of a monster storm. And it can take communities weeks, months and even years to recover.

But there are other ways people can suffer, especially children. Ways that are not always readily apparent but can rip apart families as forcefully as high winds and walls of water.

The trauma of surviving a hurricane can cause some children to develop depression, separation anxiety and other mental health issues. It can leave families struggling to preserve their relationships.

As the next hurricane season approaches, storm survivors are still overcoming the trauma.

Our investigation

A team of WUFT journalists looked into the unseen trauma of weathering a storm like last year’s Category 5 Hurricane Michael, which devastated the Florida Panhandle. WUFT spoke with survivors and researched solutions help children and families overcome the mental and emotional aftermath of a hurricane.

“I want their lives to be normal again, or at least some type of normal,” Nichole says. “I know it will never be the same and they’ll remember it forever, but I need them to stay strong and fight with me. I’ll do anything to make that happen.”

For kids, the aftermath can feel alien. With little control of their lives in the first place, additional chaos can make feeling OK harder, Dr. Royce Gray, a psychologist at Emerald Coast Behavioral Hospital in the Florida Panhandle, said.

“It’s a little more difficult for them to feel safe, to begin with and to interpret what makes them safe versus what makes them feel unsafe,” Gray says. “So this traumatic experience definitely made the vast majority of children and adolescents feel unsafe.”

The signs of stress they exhibit after hurricanes include nightmares and worse performance in school.

Former Federal Emergency Management Agency Director Craig Fugate says federal aid organizations have to rethink offering mental health services to kids.

“Children are not small adults,” he says. “The tendency is that as we write and develop our plans, and we look at impacts to communities, we tend to frame it in the context of adults and not children.”

After Hurricane Katrina, officials realized children relied on routine, like going to school, to recover.

Another important part of helping children was being open when talking about what happened.

“We want to make sure we’re comforting and reassuring children,” Fugate says. “We don’t want to tell them false promises that everything’s going to be back to normal very quickly when it won’t.”

Long after the storm

Grasping his mom’s sweater, Jace Carlson whispers into her side, “Don’t leave me.”

The 5-year-old’s small hands hold on to her shirt with no intention of ever letting go.

Brianne Carlson whispers back assuring her little boy as they walk, promising to see him later in the day.

As the pair approaches Jace’s kindergarten classroom door, the smiling cutouts of apples and other cheery decor don’t brighten Jace’s mood. Every morning before school since Hurricane Michael hit the Carlsons’ Panama City home, Jace cries when his mom says goodbye.

The family of four was stranded at Bay Medical Sacred Heart the day Category 5 winds whipped through their neighborhood street, knocking aside trees and signs. Brianne works as a nurse at the hospital, and she felt like it was the safest place to evacuate to.

Hunkered down in a second-floor waiting room of the hospital, Brianne’s family passed the time as she helped patients. Now, four months after the storm, Jace fears every moment he is without his mom or family.

For Jace and other students, their worries will continue after the next hurricane season begins. A quarter of students surveyed three years after Katrina still displayed trauma symptoms and depression, according to a report published in the American Journal of Orthopsychiatry.

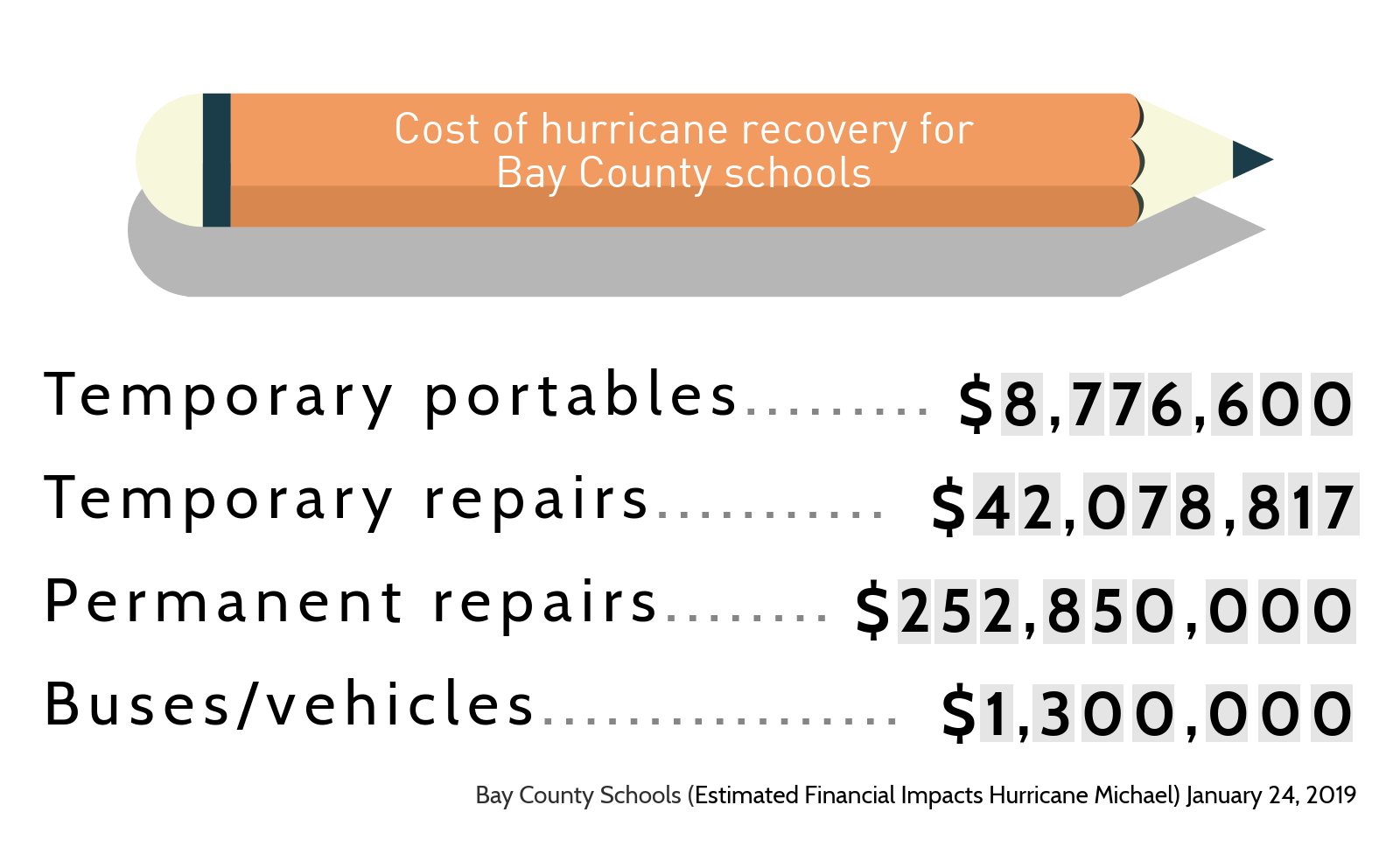

In Florida’s Bay County School District, officials are still registering more students as homeless as families come to accept their demolished trailers are uninhabitable.

The time it takes families to come to grips with their living situations can also delay care, Gray says.

The storm path ahead

There was a point during the storm when Nichole felt thankful.

After the constant whistle of the winds whipping through the neighborhood subsided while the eye passed, Nichole stood up from where she was hunkered down in a hallway. She thought they might be safe.

Her family evacuated from their mobile home to a friend’s house. The friend had already barricaded french doors that had flung open, and aside from the ear-splitting sound of the wind trying to rip apart their roof like shredded paper, she wondered if that was all.

Nichole peeked out a window and down the street. Nothing was the same.

The landscape had completely changed. She later found debris from all over the city in her front yard — from window shutters to an entire water well.

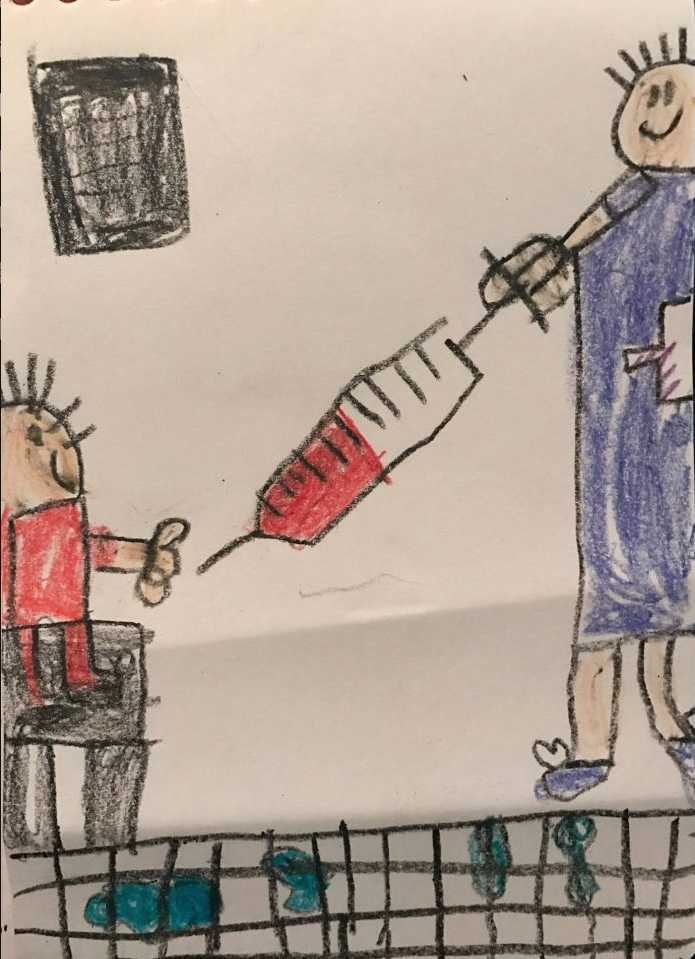

Bay County residents take in the damage Hurricane Michael caused on their neighborhood less than 24 hours after Hurricane Michael made landfall in the U.S.Now, nearly half a year since then, her daughter Marlee won’t stop wiping after she uses the bathroom. She whimpers when she sees cracks in walls. Jonathan is prescribed antidepressants after his mom found texts on his phone about hurting himself with a needle.

Nichole says her kids weren’t like this before the storm, the constant moving, and seeing debris still lining the street.

She thought about leaving, getting away from the downed trees that haven’t been removed yet and the traffic caused by increased construction. She wouldn’t be alone — about 500,000 people left New Orleans after Katrina, never to return. Bay County Public Schools’ enrollment dropped by about 2,500 students after Michael.

But running from your problems isn’t a solution, Nichole says.

“It’s like you can’t escape it,” she says. “When you go out of the city limits and you get away from it, you actually see trees again, it makes you happy, but then you come back and reprocess it all again. I’m trying to get unstuck.”

Survey: People with serious mental illness

(function(d){var js, id=”pikto-embed-js”, ref=d.getElementsByTagName(“script”)[0];if (d.getElementById(id)){return;}js=d.createElement(“script”); js.id=id; js.async=true;js.src=”https://create.piktochart.com/assets/embedding/embed.js”;ref.parentNode.insertBefore(js, ref);}(document));

Up next: Mental Health»

Special Report from WUFT News

Special Report from WUFT News