For a century, the glass bottom boat tours at Wakulla Springs celebrated Florida’s seemingly endless depths of clean, clear water. Today, with the water too murky to see through the glass, the boats are grounded — a symbol of the pollution plaguing the state’s freshwater and the cascade of consequences to come.

Luke Smith glanced back at the passengers fixated on the glass portal to the watery world below.

Below them, silvery fish darted below in water as clear as the glass they were looking through. The passengers hunched over to peer into the underwater world and take in its mysteries. Mastodon bones from millions of years ago lay waiting to reveal secrets of a newly born Florida. Vegetation whispered in patches along the bottom, providing hidden homes and hidey holes for the creatures that lived below.

Smith knew exactly where in the springs those creatures were.

“A-a-a-a-alright Henry!” he chanted. “Meet us at the po-o-o-o-le. Wake up now ’cause you he-e-e-a-a-a-rd what I said.”

Smith’s glass-bottom boat tour was a mix of talk and song, a well-honed performance that entranced his audience as he taught them about the mysterious depths of Wakulla Springs.

As if on cue, a fish “leapt” over a pole. Henry, the famous “pole-vaulting” fish, was rubbing his gills against the rod to clean them. But to the viewers, he appeared as skilled a pole vaulter as any track and field Olympian. Overjoyed by the spectacle, the group clapped and squealed with glee. Henry was always a hit.

This was the average day for Luke Smith. Born in Wakulla County in 1901, the African American boat operator guided tours of the blue underworld day in and day out.

Operating the motorized glass-bottom boats was a heck of a lot easier than when he first started—rowing small boats with five to eight tourists peering into the clear waters with a glass-bottomed bucket.

Smith and other African American tour operators were some of Florida’s first nature guides. They described the vegetation — “nature’s flower box,” and 14 species of fishes — bream, catfish, bass. They shared Native American lore: “Mysteries of strange water,” Smith would share the meaning of the name “Wakulla.” The bottom seemed so close, as if you could reach deep down and stretch your legs long enough to skim the bottom.

As it drew tourists, Wakulla Springs was also a summertime staple for local Floridians. Year after year, kids would climb the old wooden tower proving they were courageous enough to take the plunge—not only from the first platform, but from the daunting heights of the second, too.

The constant 72-degree water provided icy relief on the hottest of summer days and a glassy spectacle for those quieter winter days when the manatees would seek refuge from the chilly Gulf of Mexico.

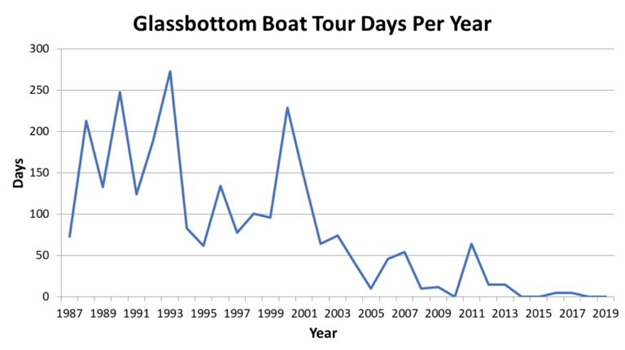

This was Florida. The real Florida. But today, this Florida is vanishing as its famous waterways become polluted. The once clear water of Wakulla Springs is a symbol for the state. The water has become so murky that the glass bottom boat tours no longer run regularly.

They sit waiting like ghost ships in the night, patiently lingering for their next riders. The legacy of Luke Smith and his enchanting stories are no longer ferried across the water.

Wakulla Springs has been identified by the state’s Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) as one of the two dozen historic first-magnitude springs in Florida in need of restoration and protection.

It is another victim of the Anthropocene.

Human burdens

Wakulla Springs is fed by the Floridan Aquifer.

As rain and other surface waters filter down to the aquifer through the porous limestone that underlies Florida, it carries with it all traces of human existence. As water flows underground to Wakulla County, just south of Leon County, it carries pollution from septic tanks, sewage-treatment systems, agricultural runoff and a myriad of other burdens.

A striking example of the resulting harm is nitrogen leaking from septic tanks, which use a drain field to treat sewage from homes that are not connected to centralized wastewater treatment plants. Many septic tanks, particularly old ones, allow excess nitrogen to seep through to the swiss cheese limestone and pollute the aquifer, Robert Deyle, vice president of the Wakulla Springs Alliance, explained.

The aquifer, in turn, feeds the springs.

There are approximately 9,000 homes in southern Leon County’s “Primary Springs Protection Zone,” where the soil is more permeable and allows more pollutants through to the aquifer, according to Leon County Commissioner Bill Proctor.

As excess nitrogen filters into Wakulla Springs, it can fuel the growth of algae that smothers native vegetation, allowing nuisance weeds and invasive plants like hydrilla to outcompete and take over the ecosystem.

This over-abundance of plant life that depends on nitrogen, particularly algae, propagates a greenish color in the water, according to the McGlynn lab in a three-part study to measure water quality and visibility. The high nitrogen levels can lead to the formation of algal mats that can shade out native vegetation, already burdened by the invaders.

On a rainy day, things can get much more muddled.

The darkened water conditions are a result of tannins, leaves that stain water a brownish-red, similar to steeped tea. Rains allows these tannins to leach organic matter, creating even muddier brown water.

Tannin buildup in Wakulla and other springs isn’t all natural. While a moderate amount of tannins in the springs is normal, the excessive buildup that has distorted the water’s clarity and ended the glass bottom boat tours is a result of human impact.

Wakulla Springs is connected to a variety of other springs through an elaborate network of underground waterways. Among these are over a dozen springs that make up the Springs Creek Springs Group. When rainfall is scarce, saltwater from the Gulf is no longer blocked by the spring’s outflow. Contaminating salts can form a “plug” that limits the spring’s freshwater from flowing out into the Gulf, Deyle explained.

As a result, connected springs like Lost Creek reverse the direction of their flow. Instead of bubbling up from the aquifer, Lost Creek dumps in and flows north to Wakulla Springs. The discharge carries the color-leaching tannins that turn the water dark brown.

Groundwater overpumping aggravates the problem, as pollution concentrates in shrinking water bodies. An estimated 3.6 billion gallons of groundwater are pumped in Florida every day, according to the US Geological Survey. And demand may be growing in one of the nation’s fastest-growing states, with an estimated 950 people moving to Florida every day, according to a 2020 Miami Report.

One study found a correlation between the duration and frequency of these reversal events and an increase in algae proliferation, meaning each cause of color changes to the springs may be exacerbating the other.

Other factors, like climate change, continue to pose threats to Wakulla Springs and worsen existing problems.

Septic tanks depend on a protective layer of unsaturated soil between the drain field and the aquifer. As climate change drives more frequent extreme weather events, which can raise the water table, it reduces that important soil layer. Improperly treated wastewater can make its way to the groundwater—not only soiling springs, but the drinking water source for 90 percent of Floridians.

The increasing rainfall can also reduce the amount of oxygen in the soil, a critical component that helps breakdown pathogens in the wastewater, according to a study on wastewater management.

The accumulating harm also poses a threat to Wakulla’s wildlife, an indicator of the declining health of the ecosystem as a whole.

Several bird species, including ospreys, are on the decline. Others birds, like anhingas, are altering their habits to accommodate the changing ecosystem by consuming crayfish, whose populations have been high as a result of all the decomposing organic matter.

Other species remain, but hidden under the darkened waters, decreasing the sights to see on the remaining boat tour, the jungle cruise.

Pushing for Progress

With continuing research and attention on Wakulla Springs, citizens and scientists, advocates and state and local leaders are working to return the watery wonder to its former beauty.

One of the first, notorious culprits of nitrogen pollution came from the state capital, itself. For decades, Tallahassee disposed of treated wastewater in spray fields used for irrigation. The practice led to heavy nitrogen infiltration into groundwater that ended up in Wakulla Springs, according to a report by the US Geological Survey.

Tallahassee invested in a $227 million upgrade to its water-treatment system to remove about 75% of the nitrogen from the water so it meets state-regulated levels.

However, Deyle said those levels are still being debated among experts as to whether they are enough to balance the ecosystem. And not all the area’s waste flows through the treatment plant. Nitrogen from wastewater has been sneaking into the springs through outdated septic systems that don’t have the technology to remove nitrogen before it is leaked into drainfields.

Even many modern systems leak more nitrogen than they did when they were initially installed. A 2010 study found that numerous septic systems in Wakulla County were releasing three times more than the amount of nitrogen allowed by ordinance.

The work to repair and restore the spring is a race against time and unprecedented growth.

In 2018, Leon County launched the first phase of its septic-to-sewer project, totaling $9 million so far in state grants to improve water quality problems arising from septic tanks in the Primary Springs Protection Zone.

So far, Leon County has removed 252 septic tanks, according to Michelle Presley, public information specialist in Leon County. The county’s strategic plan aims to remove 500 more by 2026.

There are 50,000 septic tanks between Leon and Wakulla County. Yet even as local leaders work to take out old septic tanks, they are allowing new septic systems to be installed every day.

From 2015-2020, over 500 new septic tanks were installed in Leon County and Wakulla County each, according to the Florida DOH.

While improved or inspected septic tanks can pose less of a threat for leaking nitrogen, they are not a permanent solution to a persistent problem. And Wakulla County is growing. The county has grown almost 10% from 2010 to 2020, according to Florida’s Office of Economic and Demographic Research.

In 2021, Wakulla County announced funding from the DEP for its own septic upgrade and sewer connection project. It will connect only 50 homes to central sewer, and use the balance of funds to upgrade other septic systems in the area.

Proctor, one of the Leon County commissioners, said he hopes next steps will include collaboration between the two counties on research, education and other solutions.

Wakulla Will Not Be the Last

Florida has the largest concentration of freshwater springs in the world.

Wakulla Springs is just one of Florida’s 1,000 freshwater springs. But it offers a warning for what may be to come—and what has already started—for other iconic springs.

Silver Springs still runs its historic glass bottom boat tours but is dealing with its own host of threats, including excessive nutrient pollution. The spring’s nitrate-nitrogen concentration is 3,100 percent higher than it was naturally, according to the Florida Springs Institute. A key point in its recommended plan for restoration: remove septic tanks, the source of a quarter of the pollution, and connect the houses to a central sewer system.

Two dozen other springs have been identified as nitrogen-impaired and are undergoing projects and research to solve their chemical imbalances. On this list is the famous Weeki Wachee Springs, best known for its mesmerizing mermaids.

Rick Kilby, author of several books about springs, remembers the magic of watching the Weeki Wachee mermaids swim around behind their glass enclosure. The water, “clear as gin,” made it look as if their hair was being pulled up by strings.

That clarity has begun to diminish with Weeki Wachee’s own nitrogen pollution, 30% of which has been identified as coming from septic systems in the area.

Other factors are also to blame. Agricultural runoff, groundwater overpumping, the warming climate and other pressures of the Anthropocene all have roles in the deterioration of many springs. Where people a century ago looked passively through the glass to enjoy them, scientists and advocates said it will take working together to save them.

C’mon Henry

People’s passion for the springs is evident across the state: the wonder of the Weeki Wachee mermaids, the relaxation of tubing down the Ichetucknee, the awe of listening to Florida folklore on the glass bottom boat.

“A lot of people will go to a spring like Ginnie or Ichetucknee and think it’s clear enough,” Kilby said. “But that’s because they never saw it before it was like this, before it was polluted.”

Wakulla offered a look into the primitive Florida.

The sights probed the imagination of every passenger on that boat. It allowed each man, woman and child to be a pioneer discovering Florida for the first time.

It gave us guides who understood it and spoke to its enchantments. And foreshadowed its future.

In the wise chants of Luke Smith, “Wake up now ’cause you he-e-e-a-a-a-rd what I said.”

This story is part of the UF College of Journalism and Communications’ series WATERSHED, an investigation into statewide water quality marking the 50th anniversary of the Clean Water Act, supported by the Pulitzer Center’s nationwide Connected Coastlines reporting initiative.

WATERSHED

WATERSHED