a collaborative reporting project from the University of Florida and the University of Missouri

The Price of Plenty

Chemical fertilizers help feed the world – at increasingly steep costs to people and the planet.

Few inventions have changed the world like synthetic fertilizer. Without it, the planet’s population would be roughly half what it is today. Scientists learned to mine nutrients from the ground and pull chemicals from the air to boost food production and make farming more efficient.

But fertilizer manufacturing and use also threaten human and environmental health. The energy-intensive industry emits more heat-trapping gases than global aviation, while leaving an unfair industrial burden on low-income communities. Meanwhile, less than half of fertilizer spread on fields is taken up by plants. The rest pollutes air and water, contributing to climate change, toxic algae and oxygen-depleted water where life is snuffed out.

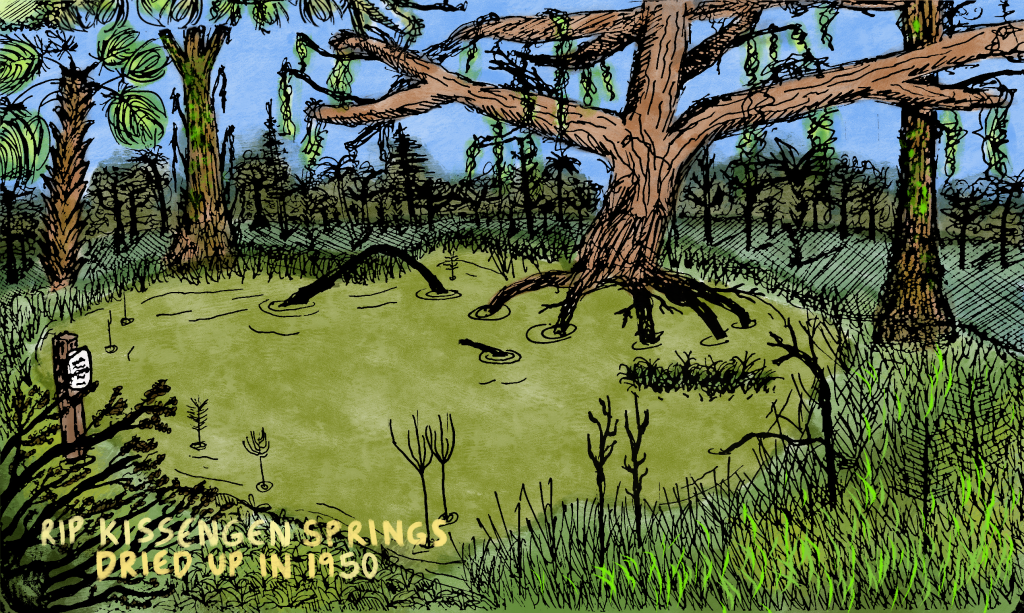

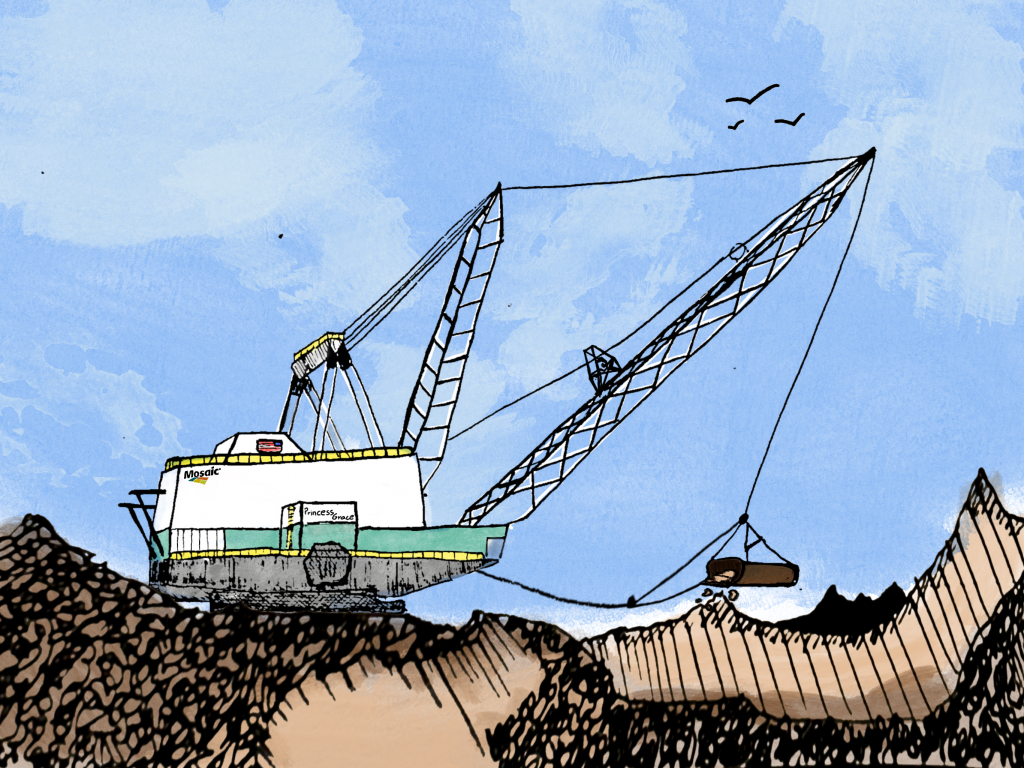

Funded by a grant from the Pulitzer Center’s nationwide Connected Coastlines reporting initiative, The Price of Plenty teamed up student journalists from the University of Florida and the University of Missouri to report on fertilizer from the ground up. They reported from Florida’s “Bone Valley” where 8-million-pound earth movers strip-mine phosphate; from agrichemical plants along the Mississippi River; from farm fields and legislative hallways; from communities stuck next door to the industry; and from the Gulf of Mexico’s “dead zone,” where it threatens one of the world’s most productive fisheries.

Student journalists found that the industry wields outsized political power; that farmers have little incentive to use less; and that nutrient pollution persists despite exhaustive science linking fertilizer to toxic algae outbreaks and other problems. They also found that while government and industry research funding pours into fertilizer application and future markets such as hydrogen power and rare earth elements, there is a dearth of research on the human health risks associated with fertilizer production – from Florida’s reclaimed phosphate lands to Louisiana’s chemical plants.

They also found promising signs of action and change. An upswing in regenerative farming practices is helping to restore polluted waterways and fight climate change. Fenceline communities next door to the industry are becoming increasingly organized in pursuit of environmental justice. The student journalists also report on solutions that rethink food production and the industry’s waste. “If we can all put our heads together, then we can come up with solutions to make sure this does not exacerbate in the future or repeat itself,” said University of Florida soil and water science professor Jehangir Bhadha. “At the same time, the demand for producing food has gone up, so we are in a very tricky place. We have to be able to talk openly about these issues to be able to come up with solutions.”

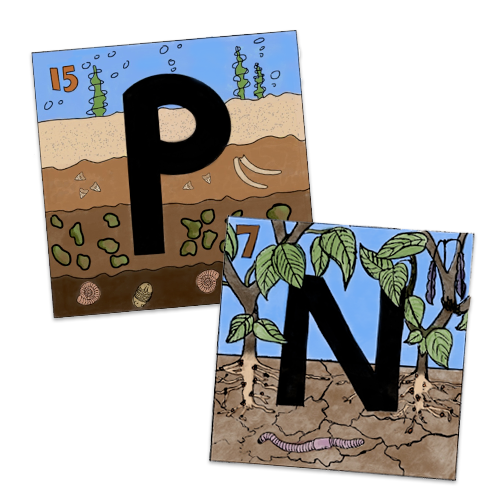

Part I: Elemental

Phosphorus and nitrogen, fundamental elements for life, are also key ingredients in fertilizer. Their discoveries and chemical production fed the world – and continue to harm it.

Part II: Justice

Citizens who live in the shadow of phosphorus and nitrogen chemical operations carry the industrial burden of fertilizer for an entire nation.

Part III: Water & Land

From the moonscape phosphate mines of Florida’s Bone Valley to the Gulf of Mexico “dead zone” that threatens one of the nation’s most productive fisheries, the fertilizer industry has profoundly changed water and landscapes in the American southeast.

Part IV: Profit

Soaring fertilizer prices have led to record profits for the industry in recent years. Meanwhile farmers struggle with the rising costs of fertilizer – and the entire planet with the rising greenhouse gas emissions tied to its production.

Part V: Futures

From recycling rare earth minerals out of phosphate waste to regenerative agriculture that aims to save soils, a more sustainable future is possible. What will it take to change such entrenched systems of producing food and fertilizer?

The Price of Plenty

The Price of Plenty