Digging into the Dirt

How the fertilizer industry funds research

By Jamie Holcomb

Research on fertilizer use and runoff by public land-grant universities in the Midwest is being funded in part by the fertilizer industry itself, raising concern about industry influence on public research.

While the U.S. Department of Agriculture still makes up a major part of funding dollars for research, private corporations and industry interest groups provide an increasingly significant portion of funding.

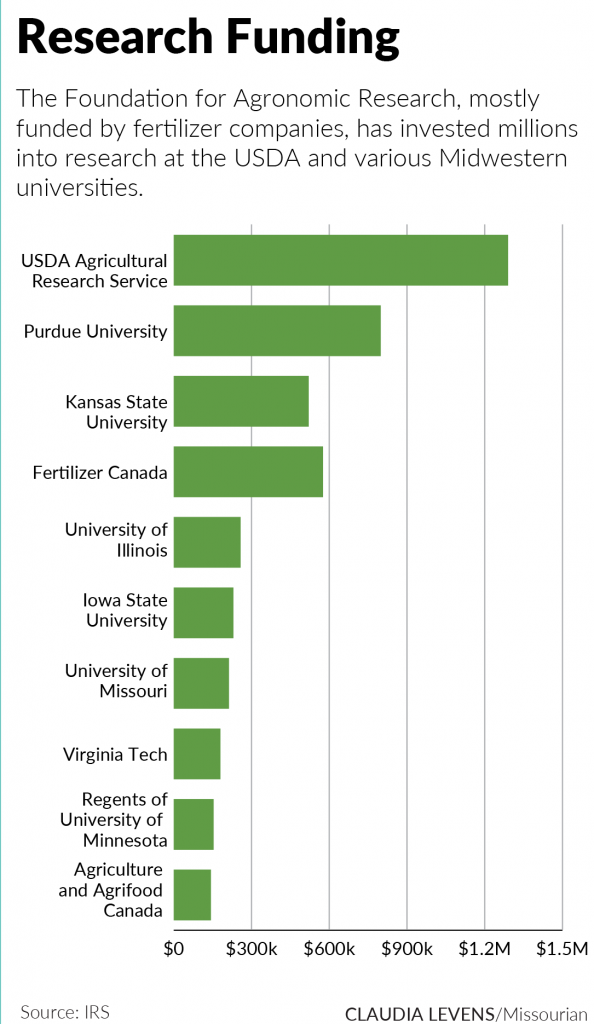

One industry-related nonprofit, the Foundation for Agronomic Research, funds many projects at Midwestern public universities, including the University of Missouri.

The Foundation was established in 2013 as an offshoot of The Fertilizer Institute, which calls itself “the voice of the fertilizer industry.” The Fertilizer Institute is both a lobbying organization that spent $1.3 million lobbying in 2022 and an education organization that shares industry knowledge with its members.

The Foundation for Agronomic Research is funded almost entirely by fertilizer companies, according to its public tax forms. In 2019, it received more than $1.7 million from companies including The Mosaic Co. and CF Industries Holdings, two of the largest fertilizer producers in the world.

The foundation’s mission is to “ensure that industry priorities are maintained and a consistent 4R approach is executed,” according to its website. 4R refers to best practices in fertilizer application that farmers should use to reduce nutrient runoff: “right source, right rate, right time, and right place.”

The main nutrients in synthetic fertilizer are nitrogen and phosphorus, which can wash off farms and into waterways, causing toxic algae blooms and hypoxic zones where aquatic animals die off from lack of oxygen.

Over the past 10 years, the fertilizer industry has invested more than $8 million into research through the 4R Research Fund, said Leanna Nigon, The Fertilizer Institute’s director of agronomy.

Data from the foundation’s tax forms shows that it gave grants totaling about $4.8 million from 2014 to 2019, with the majority of research dollars going towards universities in the Midwest. Major recipients include Purdue University, Kansas State University and the University of Illinois.

The University of Missouri received two awards for more than $200,000 total in 2018 and 2019, according to the Foundation for Agronomic Research’s tax forms.

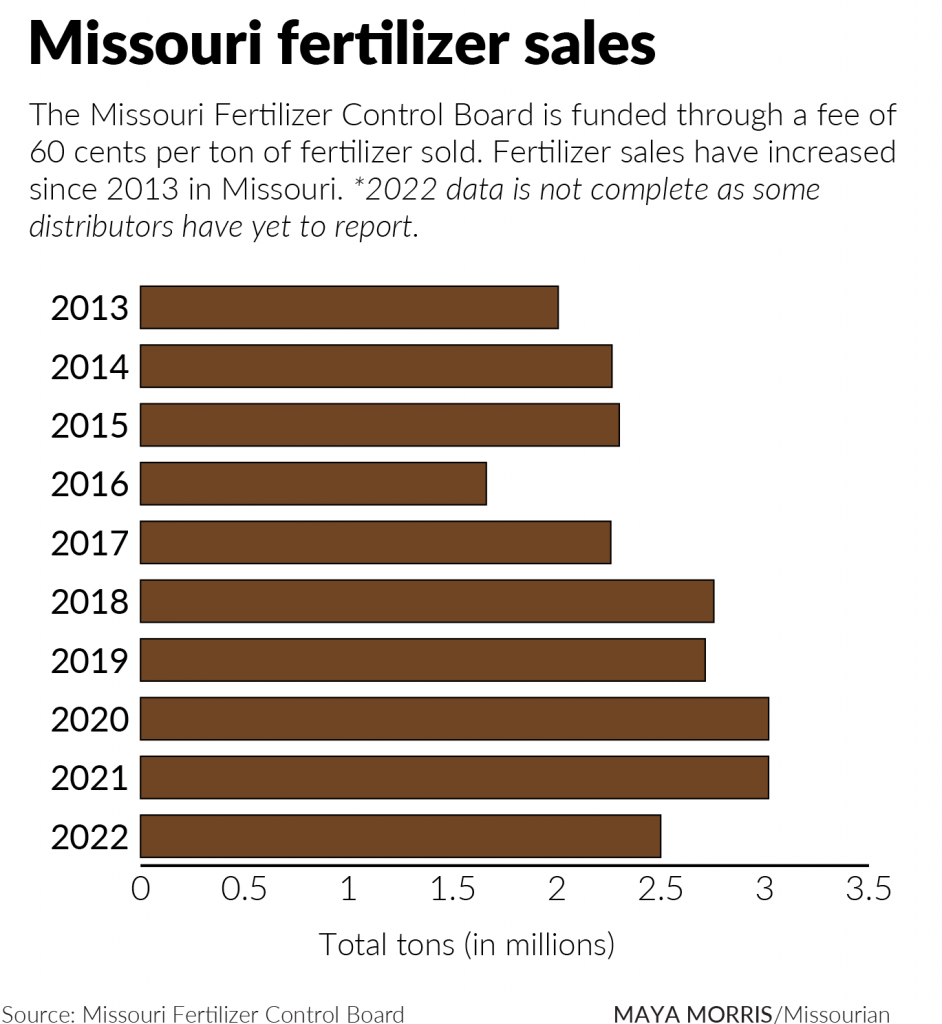

In Missouri, more research funding comes from the Missouri Fertilizer Control Board, a quasi-state agency created by the state legislature in 2016 to regulate fertilizer sales. The Board is made up of five farmers, five representatives from fertilizer manufacturers or distributors, and three at-large members, according to its website.

It is funded through a 60-cents-a-ton fee that fertilizer sellers pay. Its operating budget is based on how many tons of fertilizer retailers sell.

Like the Foundation for Agronomic Research, the Board funds research related to best management practices and nutrient runoff.

The University of Missouri has received around $1.8 million in research awards from the Missouri Fertilizer Control Board since 2018, according to data from MU’s research analytics database. The proposals and awards are focused on 4R research, along with general nutrient management.

Industry funding, public research

Industry-generated funding sources have grown as public funding for agricultural research has fallen by about one-third since the early 2000s. According to a USDA report on research funding, land-grant universities make up over half of public research and development expenditures.

Land-grant universities such as the University of Missouri were established with the help of the Morrill Act of 1862, which allowed the federal government to sell land to states for colleges. There’s an emphasis on agriculture and mechanical arts, making them the ideal place to research agronomy and fertilizer methods.

Hani Morgan, a professor and researcher at the University of Southern Mississippi who studies the influence of industry funding in various research sectors, said the increase in private funding creates more opportunity for influence over research.

“It seems to be more of a problem than it used to be,” Morgan said. “Universities are getting less funding than they used to. So very often, they have to find ways to be competitive with other universities, and in terms of the research that they produce.”

Morgan’s study has found that industry-funded research can have a “corrupting effect.”

Influence over research can look like changing research methods, leaving out certain data and contracts between researchers and corporations that stipulate exactly what they’re allowed to study, Morgan said.

While Morgan hasn’t studied the agricultural or fertilizer industries, industry influence on research has been studied in many other industries, including pharmaceuticals and nutrition.

Several researchers who have received funding from the Foundation for Agricultural Research said that the process feels autonomous, with little influence from the Foundation on the research process.

Matt Helmers, a researcher at Iowa State University, has completed two projects with funding from the Foundation for Agronomic Research and has also served on the Foundation’s Technical Advisory Board. This board identifies areas where research is lacking and helps guide decisions on project funding.

His current project, called Nutri-Net, examines the impact of nutrient management on crop yield, emissions, water quality, soil health and other environmental indicators. Nutri-Net has eight research sites in the Midwest to study these issues. Helmers said he had support from Iowa State University for his team’s research as well.

“We made sure that the research that was being done was going to be applicable to farmers and to the industry,” Helmers said.

Lindsay Pease, a researcher at the University of Minnesota, had a similar experience with funding from Foundation for Agronomic Research. Her team’s project focuses on nutrient runoff in the Red River Basin area that covers parts of Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota and Canada. It was funded in part by the Foundation and in part by commodity groups.

“I do think that actually having the fertilizer companies pay into an organization like the 4R Research Fund helps kind of buffer a little bit from anything that could be seen as maybe biased or unfavorable to a particular company,” Pease said.

After proposals for research are approved for funding by the Foundation, it becomes a hands-off process, Nigon said. The Fertilizer Institute doesn’t have control over research methods, final data or whether or not to publish the researchers’ findings, she said.

A focus on funding 4R research

Funders also help set priorities for what kinds of research get support. Both The Fertilizer Institute and the Missouri Fertilizer Control Board focus on implementing the 4Rs on farms.

The fertilizer industry designed the 4Rs to promote the best practices for farmers to reduce their nutrient runoff, and the method has become widespread over decades. In theory, 4R management benefits farmers because it keeps more fertilizer on the farm while maximizing yield. In practice, only about half of fertilizer applied is used by crops; the rest is lost to water or air.

“Most folks have room to grow, but at the same time are also very cognizant of what they’re applying and when because, quite frankly, it’s very expensive and farmers don’t want that material to wash off or go into surface waters,” said Andrea Rice, director of research, education and outreach at the Missouri Fertilizer Control Board.

Though the fertilizer industry has spent millions on research on the 4Rs, some critics say the method doesn’t go far enough to reach conservation goals.

The Center for International Environmental Law published a report last year detailing the links between the fossil fuel and fertilizer industries, calling the 4Rs an industry narrative designed to maintain the use of agricultural chemicals.

“This framework calls for using synthetic fertilizer more efficiently instead of curbing its usage, thus ultimately locking in toxic pollution and fossil fuels,” the report said.

Tom Buman, a consultant with Precision Conservation in Carroll, Iowa, said that for too long the 4Rs have been promoted as a “silver bullet” for conservation efforts.

“It should never have been thought of as a one-size-fits-all, solve-all-the-problems kind of thing,” Buman said.

Instead, Buman advocates for tailored solutions based on region and farmland, rather than just relying on 4R for every farmer. Other solutions, like vegetative buffers, cover crops and filter strips can be used along with the 4Rs to reduce runoff.

Notably, a study from the Raccoon River Watershed in Iowa showed that if all farmers adopted 4R methods, it would only “achieve about 15-20% of Iowa’s total nitrogen and phosphorus reduction goals,” according to an article published by Buman.

And an article published by the USDA in 2016 made the case that instead of focusing solely on the 4Rs, there should be 7Rs. This would add right product, right scale and right application practice to the existing four practices.

Placing the responsibility for fertilizer use on agricultural retailers and farmers also shifts blame away from fertilizer companies and society as a whole, Buman said. If nutrient runoff could be solved with the 4Rs, then that would take away incentives for other sustainability practices, he said.

Buman said the 4Rs are a good place to start, as they are backed by science, but they aren’t the place to end either.

“In itself, the 4Rs is not enough,” he said.

This story is part of The Price of Plenty, a special project investigating fertilizer from the University of Florida College of Journalism and Communications and the University of Missouri School of Journalism, supported by the Pulitzer Center’s nationwide Connected Coastlines reporting initiative.

Read Next: Part V: Futures

The Price of Plenty

The Price of Plenty