Your money and the climate are up for debate in this year’s farm bill

Congress has a chance once every five years to transform conservation in agriculture. Will they take it?

By Lauren Hines-Acosta

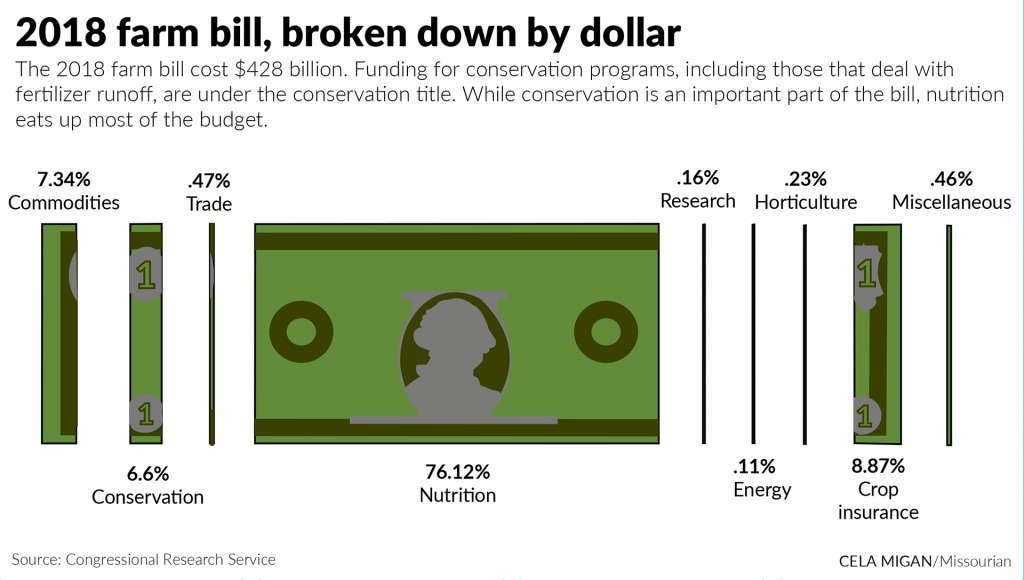

Amid concerns over national debt, Congress is under pressure to pass its first trillion-dollar farm bill this fall. The legislative package, projected to cost an estimated $1.5 trillion over 10 years, could have big implications for conservation in agriculture – including the production and use of fertilizer.

The farm bill, which goes up for renewal every five years, addresses fertilizer use indirectly by setting the direction for agriculture policy and funding. It also includes funding for nutrition programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP.

Now Congress has less than five months to renew and update the legislation before Sept. 30, when the previous farm bill expires. Conservationists see a once-in-five-year opportunity to cut agriculture’s contribution to air and water pollution.

“I think we can lay the groundwork for the beginning of some larger-scale change,” said Sarah Carden, a senior policy advocate at the Missouri-based advocacy group Farm Action.

The farm bill and fertilizer management

Chemical fertilizers are a necessity on many farms. But too much of a good thing is a bad thing. An excess of fertilizer can pollute drinking water and create toxic algae blooms and low-oxygen zones in bodies of water that are deadly to fish and other aquatic animals. Fertilizer production and use also emits nitrous oxide from soil, methane from algae blooms and other greenhouse gases that exacerbate global warming from fertilizer production.

The farm bill pays for several conservation programs that address fertilizer and nutrient management. These programs pay farmers for more than 700 conservation practices.

The bill authorizes how much government agencies like the U.S. Department of Agriculture can spend on those programs.

Programs incentivize farmers to use conservation practices by issuing grants to help pay for implementing them. For example, buffer strips are a practice that prevents excess nutrients in fertilizer, like nitrogen and phosphorus, from getting into sources of water near the farm. That way, it reduces soil erosion and keeps expensive nutrients on the farms.

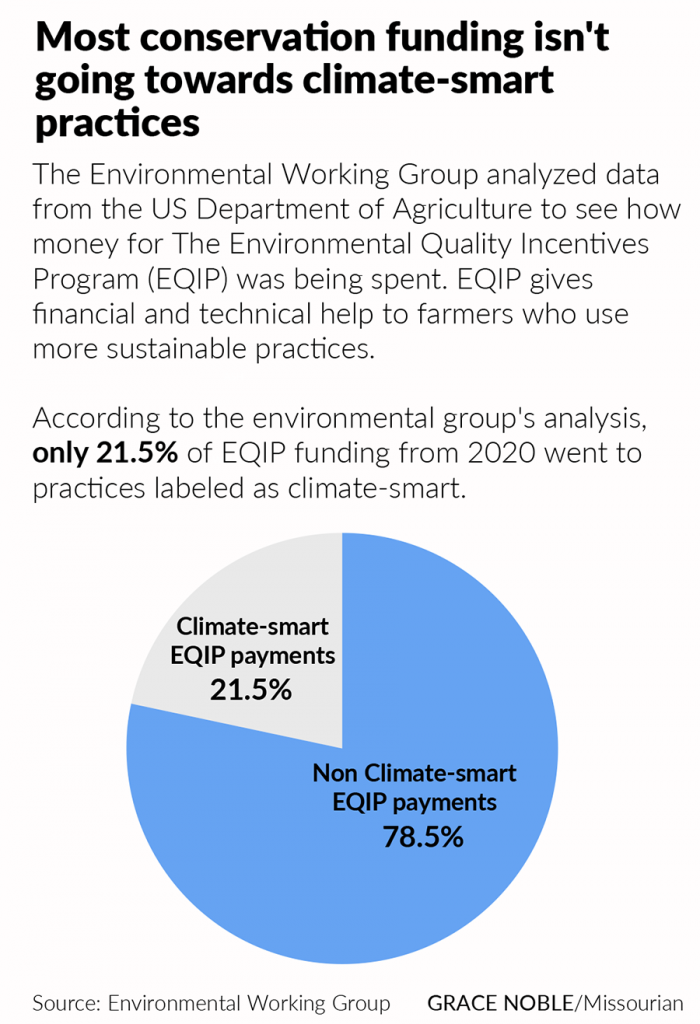

Some of these practices are better than others at reducing greenhouse gases, according to the Environmental Working Group in Washington, D.C. The environmental group determined that less than a quarter of the budget for the conservation programs in 2019 and 2020 went to practices that actually reduced greenhouse gases. Others – such as building manure pits – don’t, the group said.

Nitrous oxide is a potent greenhouse gas from fertilizer that’s almost 300 times more intense than carbon dioxide. According to the EPA, the use of synthetic fertilizer and other farm soil management practices account for 73% of all nitrous oxide emissions in the U.S.

Reducing these emissions from fertilizer is “the closest thing we have to a silver bullet when it comes to reducing greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture,” said Scott Faber, senior vice president of government affairs at the Environmental Working Group.

“We simply can’t afford to waste precious conservation dollars on practices that do little or nothing to help the environment, much less reduce emissions,” Faber said.

Conservation payments prove popular

Whether they represent the agriculture industry or environmental groups, many advocates support increased payments to farmers for conservation practices in the farm bill. Demand for these programs typically exceeds what lawmakers have been willing to dole out. According to the Institute for Agriculture & Trade Policy, fewer than half of applicants between 2010 and 2020 could participate in conservation programs.

For example, Farm Action supports the reintroduction of the COVER Act, which would pay

$5 per acre to farmers who use cover crops. Cover crops like grasses or legumes prevent soil erosion, suppress weeds and maintain nutrients in the soil.

“There are currently barriers within our farm system to using conservation farming practices, the kinds of practices that help farmers become less dependent, like cover cropping, on fertilizers,” Carden said.

The Environmental Working Group wants to increase the time on contracts to remove risky land from production under the Conservation Reserve Program. Farmers receive payments for setting aside environmentally sensitive land. Instead, they are paid to take farmland that floods frequently and plant grass and trees. Those contracts currently last 10 to 15 years.

Faber said by lengthening the contracts to 30 years, carbon stays captured in the soil longer and doesn’t escape as a greenhouse gas.

Wanted: technical assistance

The Fertilizer Institute in Arlington, Virginia, a trade group for fertilizer producers, has its own farm bill wish list. The group wants Congress to give higher priority and funding for research projects looking at the 4R framework, which refers to adding fertilizer at the “right source, right rate, right time, and right placement.”

The group is also advocating for payments that incentivize farmers to use the 4Rs.

Reagan Giesenschlag, government affairs manager at The Fertilizer Institute, said the farm bill is “for the farmers, so that’s who our priorities are around — how to increase or access these conservation programs.”

Another industry priority is to make the USDA evaluate biostimulants as a new conservation practice. Biostimulants help plants take in nutrients from fertilizer more efficiently.

In addition, the fertilizer industry, Farm Action and the American Farm Bureau Federation are pushing for greater access to technical service providers who help farmers implement conservation practices.

“Technical assistance is a big issue,” said Courtney Briggs, senior director of government affairs at the Farm Bureau. “There is a shortage of them… That’s a complaint that we hear a lot from our producers.”

Supporting domestic fertilizer production

Increased domestic fertilizer production is another priority for ag advocates.

Fertilizer prices have increased significantly since 2021, as the pandemic, natural disasters, and the war between Russia and Ukraine in 2021 exacerbated fertilizer supply chain issues.

The Fertilizer Institute supports the SUSTAIN Act, which promotes producing fertilizer domestically by labeling fertilizer’s ingredients as critical minerals. This means permits for those ingredients would be streamlined so they can be processed faster. When it’s reintroduced in the current congressional session, the group hopes policymakers will include some of the concepts in the farm bill.

Farm Action also wants more domestic fertilizer production – to create a more competitive market. The organization supports the reintroduction of two antitrust bills that would halt large agribusiness company mergers. Farm Action would like to see these included in the farm bill alongside support for conservation programs that reduce fertilizer loss.

“The fertilizer industry is highly consolidated and has a history of price gouging,” Carden said. “So we’re also addressing this indirectly by trying to liberate farmers from their dependency on the synthetic fertilizer industry.”

Last September, the Biden administration invested $500 million in expanding domestic fertilizer production to spur competition and combat price hikes.

The Fertilizer Institute filed comments with the USDA last year addressing competition and supply chain concerns.

“Past mergers or acquisitions in the fertilizer sector have not resulted in any noncompetitive conditions,” the institute wrote. “As previously stated, domestic producers compete amongst themselves and amongst a highly competitive global fertilizer business.”

Voluntary or required?

The biggest area of disagreement is whether to require, or merely encourage, farmers to adopt conservation practices. All conservation programs are currently voluntary, and the Farm Bureau thinks changing that would only make things harder on farmers.

“Flexibility is key for a lot of our producers,” Briggs said. “So the more prescriptive you get, I think a lot of the times you may deter producers from engaging in a voluntary conservation program.”

Lawmakers often have gone with a hands-off approach. At a House Agriculture Committee subcommittee hearing May 23, Republican leaders emphasized keeping programs voluntary.

“Our system of conservation delivery works because it is voluntary, incentive-based, and programs [are] locally led,” Agriculture Committee Chairman Glenn “GT” Thompson, R-Pa., said in an opening statement. “That locally led component is important because different regions have different local natural resource concerns that need to be addressed.”

However, some think the need for change is more urgent – and that mandatory measures are needed.

The Government Accountability Office, a nonpartisan congressional watchdog, has for years recommended major reforms to farm bill programs such as crop insurance and commodity payments. The GAO released a report in January recommending that the USDA and Congress tie conservation requirements to crop insurance for farmers to receive coverage.

The GAO said that increased natural disasters from climate change are a significant source of risk for the federal government. More disasters mean more damaged crops, which leads to more crop insurance claims. The USDA would need more funding and staff, but the changes could reduce the federal government’s financial risk and incentivize farmers to adopt conservation practices, the report said.

With climate change making farming conditions worse, Faber from the Environmental Working Group favors taking action.

“The magic’s in the details,” Faber said. “We’ve got to reform these programs to make climate a priority, or agriculture will soon become America’s No. 1 source of greenhouse gas emissions.”

What’s next for the farm bill?

In addition to the usual debates, interested parties are closely watching how President Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act will affect the farm bill. The 2022 legislation provides more than $19.5 billion for USDA agricultural conservation programs. Ben Brown, senior research associate at the University of Missouri Food and Agriculture Policy Research Institute, called the IRA “a historical amount of funding.” He said that may mean less money steered to conservation in the farm bill.

Some politicians want to reallocate those funds into the farm bill’s baseline. Republicans voted unanimously against the IRA – and now they want to shift some of those funds from conservation to other farm-bill programs.

“I believe that as we conduct our review of the 2018 Farm Bill’s conservation title, we must examine this enormous influx in funding and how these dollars are being allocated by USDA,” Subcommittee Chair Jim Baird, R-Ind., said in an opening statement to the Conservation, Research, and Biotechnology Subcommittee May 23.

Stakeholders on all sides are now giving their input to the House and Senate Agriculture Committees. Those bills will work their way through the House and Senate before landing on President Joe Biden’s desk later this fall. Then the nation’s agriculture policy direction will be set for the next five years.

However, the growing debate around national debt may affect the farm bill and its provisions addressing nutrition, conservation and other programs. To keep spending money on things like the farm bill, the federal government needs to increase how much debt the nation can borrow or face a shutdown.

“Conservation has received quite a bit of funding,” Brown said. “All that new funding could be at risk, and other things, if we were in a budget-cutting situation.”

If the bill isn’t passed by Sept. 30 or doesn’t get an extension, conservation programs will follow the 2018 farm bill guidelines until a new one is passed.

In the end, will the farm bill see major changes?

“There’s not broad agreement on an alternative,” Brown said. “And so as a result, we tend to get the status quo as we move forward.”

This story is part of The Price of Plenty, a special project investigating fertilizer from the University of Florida College of Journalism and Communications and the University of Missouri School of Journalism, supported by the Pulitzer Center’s nationwide Connected Coastlines reporting initiative.

Read Next: Part IV: Profit

The Price of Plenty

The Price of Plenty