When the Storm Hits

How vulnerable are the southeast’s phosphate plants, mines and mountains of waste to stronger rains and hurricanes?

By Alan Halaly

TAMPA, Fla. — Walter Smith II was shocked to see water pooling past his ankles on a street in Progress Village where his father lived, so he took a picture.

Some five or six years ago, Smith was passing through the community in East Tampa during a routine, light rain. Infrastructure meant to divert stormwater hadn’t been upgraded since the town was created in 1960 as Tampa’s first low-income housing suburb, he said. And leaders are still waiting.

“I thought, ‘Oh my God,’” said Smith, a licensed environmental engineer. “That’s a lot of water.”

The Tampa Bay region hasn’t been hit by a major hurricane since 1921, when an 11-foot storm surge plowed through. Smith can’t imagine the magnitude of flooding that would occur if Progress Village took such a hit today.

A historically Black unincorporated community, Progress Village lies in the shadow of a phosphogypsum stack — a mountain of waste topped with an open retention pond holding millions of gallons of toxic water from fertilizer production. Another stack sits about a mile west along Hillsborough Bay, a bit farther from people’s day-to-day lives.

Against Florida’s naturally flat landscapes, the towering stack is impossible to miss from some homes in nearby Riverview, the Village and two newly constructed complexes on the fenceline.

At 367 acres, the stack is bigger than the Busch Gardens zoo and amusement park that sprawls on the other side of Tampa.

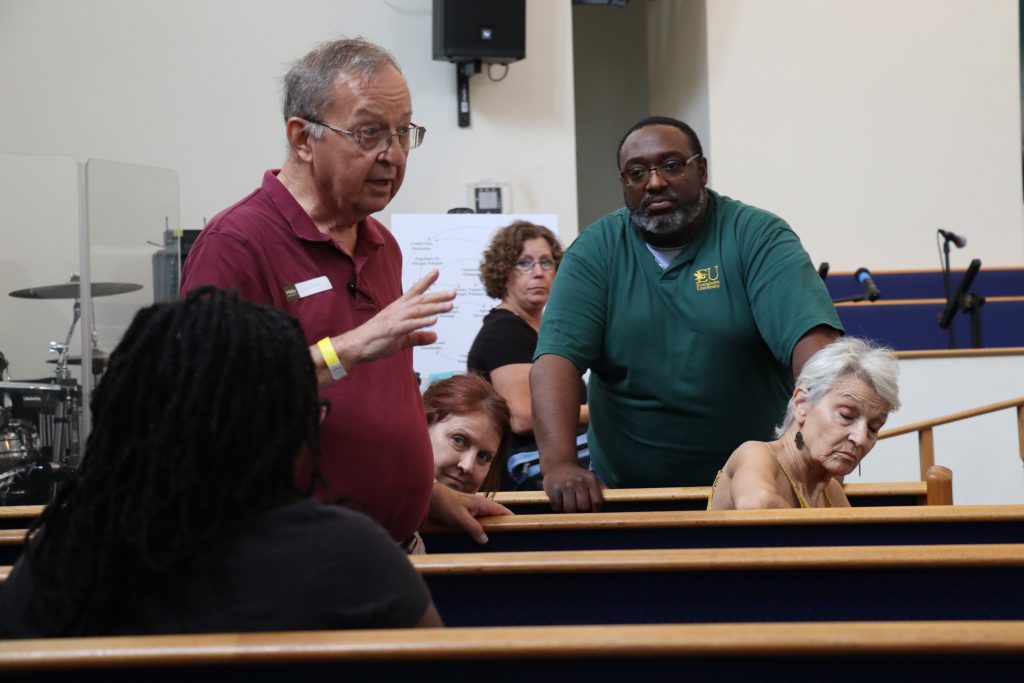

Now, some 40 years after the community unsuccessfully protested construction of what became the area’s second stack, Smith has made it his mission to educate the most vulnerable about how industry may affect the health and safety of Village residents.

Smith’s father, Walter Smith I, ultimately left town; he later served as president of Florida Agricultural & Mechanical University. Smith now worries for those who must deal with the risks of living next to a phosphate plant, two gypsum stacks and a coal-fired power plant.

“You know how people talk about forgotten places, forgotten towns?” Smith said outside the quaint Victory African Methodist Episcopal Church where he often hosts health-focused community outreach events. “This is one.”

“You know how people talk about forgotten places, forgotten towns? This is one.”

– Walter Smith II

Phosphate companies stack phosphogypsum — radioactive waste that contains uranium, thorium and radium and emits the carcinogen radon — into mountains of industrial waste. Whether it’s those “gypstacks”; phosphate mining that lays bare the earth’s underbelly in central Florida; or fertilizer processing plants in Louisiana’s so-called Cancer Alley, life in the shadow of the fertilizer industry has long been a reality for smaller, lower-income communities.

Three central Florida ZIP codes located in the towns of Mulberry, Bartow and Fort Meade carry most of the burden of phosphate mining waste, with the highest concentration of gypstacks, according to a WUFT News analysis.

Climate change may further complicate risk. Florida has the highest number of fertilizer manufacturing operations of any state in the nation, according to the IBISWorld 2022 industry report. It is also among the states facing the greatest risk of hurricanes and extreme rains that climate scientists say are growing more severe as the Earth warms.

Twenty-five phosphogypsum stacks rise across the state, according to Florida Department of Environmental Protection data, ranging anywhere from 51 to 744 acres in area. Most are concentrated in central Florida.

In other parts of the southeast, two stacks are under federal Environmental Protection Agency oversight as Superfund sites on the coast of Mississippi in Pascagoula. Other stacks, including those that hold waste from three phosphate processing facilities, rise in Louisiana.

Forty years ago, Progress Village residents packed the seats of a 1983 Hillsborough County Commission meeting to protest a permit to build a second stack. That stack is now easily visible from the playgrounds of the local elementary and middle schools.

When it was approved, some thought the community concern fell on deaf ears because of racism. “I don’t think if this site was located near an established community that was 99.8 percent white … that this company would have proposed to put this pile on that site,” Warren Dawson, the Village’s attorney at the time, said in a 1984 Miami Herald article.

As local will to fight the stack dwindled, the stack itself grew taller. The commission later quietly granted both 200-foot and 50-foot height extensions with little input from community members, according to a 2017 University of South Florida thesis by Laura Baum, who spent three years in the community documenting the Village’s story.

Several current residents from the Village and nearby town of Riverview interviewed for this project said they had never thought about what the mountain they lived next to could be.

In 1984, Village leaders came to an agreement with the company known as Gardinier, which was soon renamed Cargill. In 2004, Cargill’s crop nutrition division and IMC Global merged to become The Mosaic Co. (NYSE: MOS), a Fortune 500 company with nearly $20 billion in revenue in 2022. Based in Tampa and with major phosphate operations in Florida and Louisiana, Mosaic is today one of North America’s “Big Three” fertilizer manufacturers following CF Industries and Nutrien.

In exchange for putting up with the new gypstack, the agreement gave Progress Village residents land for a community garden, preferential hiring for locals at the nearby phosphate operations and an ongoing scholarship program, which still actively benefits local students. Cargill also reimbursed attorney fees spent to fight the stack.

The agreement set up honor roll awards of $25 per report card for local students, and a $100 gift upon graduation.

“Progress Village was strong and organized,” Baum said. “They really worked hard to have their community organization and be powerful within it. That’s the only way they were able to force the agreement.”

The water and the weather

A history of gypsum stack threats across the southeast have legitimized the initial fears of Village residents.

FDEP maintains a public database of communications between the agency and facility managers about potential spills or threats to industry infrastructure. Activists keep a close eye on the list, especially during hurricanes.

Some Floridians may have never heard of a gypsum stack until spring 2021. More than 300 homes were evacuated when officials in late March discovered a tear in the liner of a stack at the defunct Piney Point phosphate plant in Manatee County. Officials released more than 200 million gallons of polluted water into Port Manatee and Tampa Bay to avoid a worse disaster.

Two years later, Florida taxpayers have spent $85 million cleaning up the site. A court-appointed engineer is overseeing its closure. Workers are injecting a million gallons of its polluted water every day more than a half mile below ground, in a confined saltwater aquifer.

Tampa Bay saw its worst red tide in half a century the summer following the release; although some scientific studies point to Piney Point as the cause, other research is ongoing.

Meanwhile, million-gallon discharges into southeastern watersheds have happened for decades.

Most stacks are now managed by bigger fertilizer companies like Nutrien and Mosaic. This doesn’t include the two in southwest Mississippi that became Superfund sites when the EPA intervened in 2018.

Costs for the Mississippi sites have soared to $198.6 million — $95 million for stack closure and $103 million for water treatment, said Craig Zeller, an EPA remedial project manager. The project, he added, will likely be completed in 2025.

The agency lists heavy hurricane rainfall as the reason for the Mississippi discharge of 400 million gallons of partially treated waste in 2017. As of March, 5.4 billion gallons of water have been discharged into the Bayou Cossette over five years, according to EPA documents.

Phosphogypsum stacks also pose a threat for the Floridan Aquifer, the primary source of drinking water for Floridians.

Smith worries a disaster like Piney Point could be in the Village’s future, even though the stack is now under the watch of well-financed Mosaic. Many residents have long been wary of their water, coming to a consensus it isn’t safe to drink or cook with. Growing up, Progress Village Civic Council President Twanda Bradley said her family used a water purifier out of caution.

“It would be yellowish, kind of beige,” Bradley said of the community tap water in her childhood. “It wasn’t clear.”

Development on the surface can increase the aquifer’s vulnerability to sinkholes. Six years ago, a sinkhole opened up under an active gypstack at Mosaic’s New Wales facility in Mulberry. An estimated 215 million gallons of toxic wastewater leaked into the aquifer.

And that wasn’t the first time. Sinkholes triggered an 80-million-gallon spill at the New Wales gypstack in 1994, and an 84-million-gallon release in 2009 at a gypstack in White Springs, according to an E&E News report.

In the future, such disasters could be amplified by two factors: aging infrastructure and the reality of climate change, which scientists say is causing more-extreme precipitation and strengthening some hurricanes.

Storm wind speeds are expected to increase in intensity by up to 10% in the 21st century, according to model projections from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Precipitation rates may grow 10% to 15%; warmer temperatures mean the atmosphere holds more water, leading to more rain.

Meteorologists have also begun to prepare for what could be unprecedented Category 6 storms on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale — sustained winds past 200 miles per hour.

All this raises the question: Is climate change elevating the risk?

On the edge — preparing for the next storm

Another predominantly Black, unincorporated community that knows all too well the impact of the phosphate industry is Convent, Louisiana: an unassuming, quiet neighborhood in St. James Parish with 483 residents, according to the 2020 U.S. Census.

A square-mile gypstack looms at Mosaic’s Uncle Sam Plant in Convent. The phosphate fertilizer complex retained the name of the sugar plantation where more than 150 people were enslaved in the mid-19th century, according to historian Christopher Morris. Ironic given what stands there today, Morris found the rich Mississippi bottomland once thought to be infinitely fertile was so deprived of its nutrients by the 1870s that Uncle Sam’s fields had to be supplemented with fertilizers including bone black — a charcoal made of animal bones that was rich in phosphate.

In the 20th century, plantations were transformed into industrial plants along an 85-mile strip of the Mississippi River between New Orleans and Baton Rouge. It’s not just the fertilizer industry that emits toxins into the air and water along the strip, dubbed “Cancer Alley” due to high rates of cancers and other ailments among residents.

Convent is a stone’s throw from nearly a dozen plants that produce a wide range of products for ExxonMobil, Occidental Chemical, Nucor Steel and Ergon.

Industry has led Barbara Washington, a Convent resident with the local activist group Rise St. James, to swear off ever staying in her home during a hurricane or tropical storm.

She regrets riding out Hurricane Ida, the 2021, Category 4 storm that became the second most-intense to hit Louisiana since Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Locked indoors with family, destruction was at her doorstep.

“[My husband] actually called his mom and told her: ‘Mom, I love you. But I don’t think we can make it,’” she said. “When we got up that next morning, it was just devastation.”

With little assistance from the parish government or the state, the neighborhood is still reeling from the effects of Ida almost two years later. Tarps on rooftops and mold inside from flooding still mark dozens of homes in the neighborhood.

Convent’s story is one Wilma Subra, an 80-year-old environmental scientist and former EPA consultant, has heard over and over again. For decades, she’s advocated against stacking gypsum in Cancer Alley.

Like Washington, she’s wary of whether living close to industry is safe during a major storm.

“This is a disaster waiting to happen,” Subra said in Convent, gazing at a stack behind her that Louisiana state officials thought could collapse four years ago.

Mosaic’s 10-K public filing to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission acknowledges hurricanes increase water management costs, and that it may need to update its procedures amid future excess rainfall and hurricanes.

In addition to production delays due to Ida, Mosaic disclosed delayed shipments and extended down time caused by Hurricane Ian last fall. Category 4 Ian decimated entire neighborhoods in southwest Florida after initially drawing a bead on Tampa Bay, where much of the industry is concentrated.

Operating in hurricane-prone states means Mosaic officials reckon with storm preparation year-round, said company spokesperson Jackie Barron.

Even when its facilities have been in direct hurricane paths, such as during Charley and Irma, the company’s operations have survived mostly unscathed.

“It’s not to say that people weren’t concerned and paying attention,” Barron said. “But we have an incredible amount of experience in this arena. We know what to do, where to do it and how much to do it.”

There are three classifications of gypsum stacks — closed, active and inactive. In general, stacks are structurally sound, Barron said.

Closed stacks are defined as those that no longer accept waste or threaten the environment or human health.

They are covered by an impermeable liner and often a layer of grass. Closed stacks are less of a concern for extreme weather because they don’t have active ponds where phosphogypsum is still being added, said Rob Werner, the senior manager of engineering who oversees Mosaic’s 16 Florida stacks.

Inactive ones no longer accept phosphogypsum, but still hold it. Active stacks are those to which waste is continually added.

For stacks with ponds, which are regulated by the state, both an internal and external dike system keeps water impounded, preventing spillage, or overtopping, said Werner, who downplayed any risk for people living near a stack during a major storm. Potential spills are what engineers are most concerned with during a storm, he said.

So-called “trigger reports” are generated daily for active stacks, Werner said, detailing the amount of rainfall in inches that a stack can hold without the risk of a spill.

Should rainfall exceed a given quota set by a trigger report, Mosaic can redirect water to other ponds. An added layer of protection comes from a ditch around the perimeter of the external dike. Together, these systems should put nearby residents at ease, Werner said.

“As long as that dike is there, it’s not going to wash away or fall down,” Werner said. “The water level stays underneath the crest of the outer dike and the erosion action is against only the inside of the inner dike. The possibility of that overtopping or eroding out is very, very small.”

On the mining side, stormwater is managed through a diverse set of berms, or a mound barrier that separates two areas, said Keith Beriswill, Mosaic’s senior manager of geotechnical engineering.

Florida facilities also do a dry run of their hurricane plans in June, he said.

“We’re always looking throughout the hurricane season as to whether or not one of these storms may impact Florida or one of our operations,” Beriswill said. “This hurricane plan gets activated numerous times a year.”

During Ian, some mining facilities like the one in Fort Meade held in at least 10 inches of stormwater — which Beriswill said prevented further destruction of downstream communities with critical flood control.

Lance Kautz, a regulator with the FDEP’s Mining and Mitigation Program, said the facility in Fort Meade only exceeded its permitted turbidity, or the relative clarity of water. The fact that turbidity was the only issue was a remarkable feat, he said, attributable to evolving wastewater innovation.

“That kind of situation with that specific facility was probably the best that you could hope for,” he said.

But to Ragan Whitlock, a staff attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity, such talking points are just a diversion. Mosaic’s facilities aren’t helping nearby communities deal with flood risk as a whole, he said, and continued phosphate mining certainly isn’t easing concerns.

As phosphate infrastructure ages like at Piney Point — a disaster that’s currently playing out in court — threats like torn liners become more possible, Whitlock said.

“I have very little faith that any phosphate facilities or phosphogypsum stacks can withstand even a glancing blow from a major hurricane,” Whitlock said.

Canada-based Nutrien, the second-largest fertilizer manufacturer in the U.S. after CF Industries, has half a dozen phosphate operations from the midwest to the South, including at North Florida’s White Springs. Groundwater over-pumping by the phosphate industry famously dried up the former tourist attraction in the early 1970s.

Its Geismar plant in Louisiana began a closure process in 2018, brought on by a lawsuit for mishandling waste. A recent five-year review of its White Springs operations by Hamilton County showed extreme rains caused a wastewater bottleneck and other concerns at its Swift Creek chemical plant and unlined phosphogypsum stack in winter 2018. In summer 2021, heavy rains in July and again in August eroded berms, causing failures that led to turbid waters running into Long Branch, which runs into the Suwannee River.

Nutrien declined an interview but provided email responses.

“As storm predictions have improved over time — wind intensity, track, and rainfall — we have incorporated those improvements into our preparedness planning,” Jeff Joyce, general manager of White Springs Phosphate, wrote in an email. Across North America, the company launched a severe-weather program in 2022 in response to worsening risks of extremes, from record rainstorms to severe tornadoes near its midwestern operations.

Solutions: Who should carry the burden of waste?

If phosphogypsum waste isn’t best situated in stacks next to an unjustly burdened few, a question remains: Should the waste and the risks associated be equalized across the nation? The Florida Legislature thinks so.

Though the EPA had long denounced the practice, using phosphogypsum in road construction has reentered the public psyche. The agency, under the Trump administration, gave it a go-ahead in 2020 but later revoked the approval in 2021.

The Florida Legislature this year passed a Mosaic-backed bill to require the Florida Department of Transportation to study the practice, though the EPA still bans it. Aside from helping the industry with its waste problem, it could be another source of revenue for Mosaic.

Industry advocates say the use of the material is common across the world, which is what makes it plausible to James Briscoe, Mosaic’s senior operations manager.

“Our hope is, obviously, that they reapprove it so we can use it,” Briscoe said. “Like the rest of the world does.”

Barron, the Mosaic spokesperson, maintains there’s no hazard in using the fertilizer byproduct in construction. Critics say it poses an unacceptable risk to construction workers, public health and the environment.

Some activists like Glenn Compton, chair of central Florida advocacy group ManaSota-88, worry about the proposal’s environmental impacts. Advocates fear that spreading out the phosphogypsum burden from stacks to roads could contaminate the aquifer with toxic runoff, pollute the soil and emit radon gas into the air.

Compton said he finds the question of what to do with phosphogypsum to be a problem of the fertilizer industry’s own making.

“I don’t think it’s incumbent upon anyone other than the industry to come up with the solution to their phosphogypsum waste disposal problem,” he said.

But communities like the Village must deal with hazards from their porches every day.

Aside from not trusting the water, Smith believes the impact of industry to air quality also flies under the radar. Recently, he worked with researchers from USF to install an air quality monitor at a local church located a mile and a half from an open stack.

Results will be publicly available via Purple Air, a community-based effort to measure particulate matter from vehicle and industry emissions. Collecting its own data will give Progress Village a better picture of risk, Smith said, as well as leverage in any legal and other kinds of dealings with neighboring industries like Mosaic, or Tampa Electric Co., which still operates major coal-fired generators in the area.

“There’s no real evidence” of whether fertilizer and other nearby industries are safe for Progress Village residents, Smith said. “That’s why there has to be data, which is why I did this — to show people ‘Hey, you can do this. We can do something about it.’”

While communities are forming environmental justice coalitions to fight for their neighborhoods, whether intensifying climate conditions will force the southeast to reconcile with extractive industries remains to be seen.

But the onus of keeping industry in check is a task also meant for regulatory agencies with taxpayer dollars, said Brooks Armstrong, executive director of People For Protecting Peace River.

It’s vital for the government to maintain high standards and keep industry accountable, he said, especially in vulnerable periods of extreme weather.

“It seems like incrementally, FDEP will raise the standards, but it usually only happens after a disaster like Piney Point or New Wales,” Armstrong said. “But then the experiment continues.”

This story is part of The Price of Plenty, a special project investigating fertilizer from the University of Florida College of Journalism and Communications and the University of Missouri School of Journalism, supported by the Pulitzer Center’s nationwide Connected Coastlines reporting initiative.

Publication Date:

The Price of Plenty

The Price of Plenty