Gulf of Mexico dead zone researcher Nancy Rabalais leaves legacy for new generation

Scientists expect to release forecast for the size of this year’s oxygen-depleted zone this week

By Joy Mazur

COCODRIE, La. — In the summer of 1985, Nancy Rabalais set sail on a research vessel into the Gulf of Mexico — and into the scientific unknown.

Back then, scientists knew little about wide expanses of low-oxygen water, called hypoxia, that sometimes appeared in the Gulf and other bays and rivers. That summer, Rabalais’ team was set on discovering how these areas connected to creatures that dwell on the bottom of the Gulf.

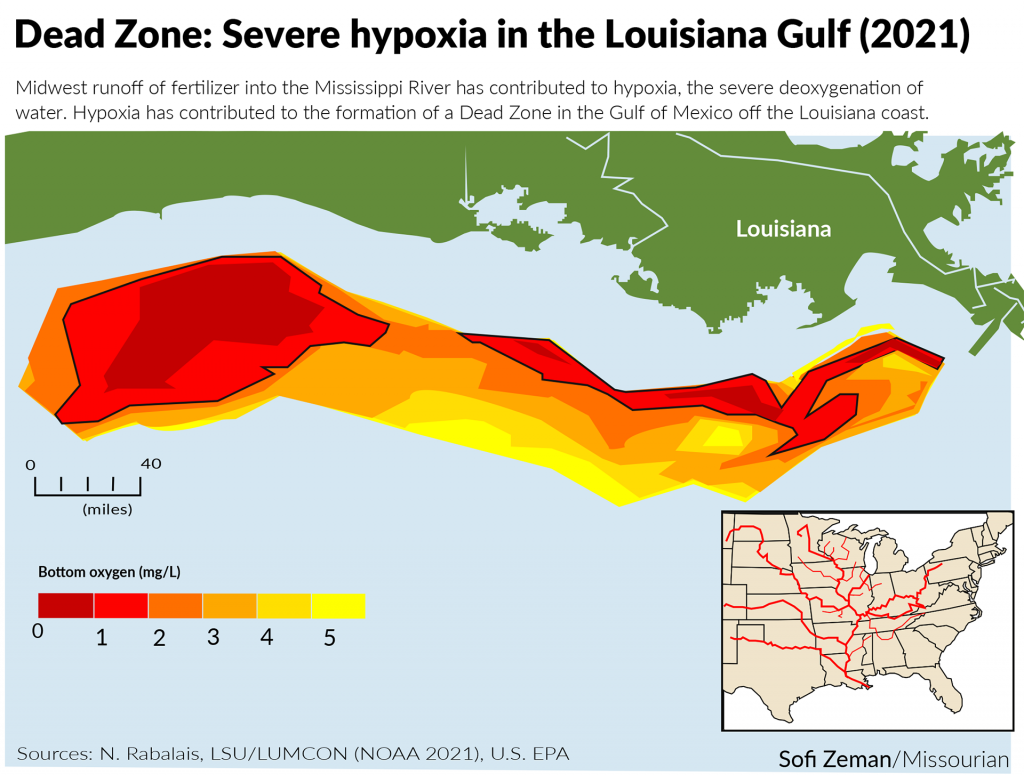

While analyzing water and sediment samples miles off the coast, the team from the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium and Louisiana State University quickly discovered that hypoxia stretched from the Mississippi River to Texas – and that it lasted for most of the summer.

Later, they pinpointed the cause: increased amounts of nitrogen and phosphorus in the Gulf, largely due to runoff from farm fertilizer and other sources in the Mississippi River Basin.

Rabalais’ research put the Gulf of Mexico “dead zone” on the scientific map and into the nation’s psyche, leading to the creation of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Mississippi River/Gulf of Mexico Hypoxia Task Force and a host of efforts to combat nutrient pollution, which EPA calls “one of America’s most widespread, costly and challenging environmental problems.”

Over nearly four decades, Rabalais has become a giant in her field. She has completed hundreds of interviews with journalists, presented a TED Talk, testified to Congress multiple times, mentored countless LSU students and published nearly 160 studies.

Now 73, Rabalais said she doesn’t plan to go on the research cruises anymore due to her age and health issues. She remains engaged in her work, even as she trains a new generation of scientists to take over.

“I believe in doing research that can support the public good,” she said. “And this is one of those ways.”

The early days

Rabalais received a simple instruction from Don Boesch, the first executive director of LUMCON, before she left for her first research cruise: “Nancy, go forth and study hypoxia.”

The rest is history — and a lot of data.

Boesch brought initial funding to Louisiana to carry on work he had started in the Chesapeake Bay, which has its own hypoxic zones caused by excessive nutrients.

At the time, Rabalais was fresh off a doctorate in zoology with a minor in marine science from the University of Texas at Austin. Born in Wichita Falls, Texas, she grew up with a love for water and studied marine science and biology throughout much of her academic career. She was certified to scuba dive at the age of 19, a skill that would come in handy while replacing monitors 60 feet under the Gulf surface.

“I just developed enormous respect for her, not only in terms of her commitment and intelligence, but her fortitude,” Boesch said.

Rabalais was in charge of the first hypoxia research cruise in the Gulf of Mexico in 1985 and directed the ship, including where and when to take water samples. Over five days, the crew split its time between day and night shifts to work full-time on the 116-foot long research vessel Pelican.

“And I was making decisions like I knew what I was doing,” she said with a laugh.

The crew set out from Terrebonne Bay and traveled about six to eight hours to reach the dead zone, where they started taking oxygen measurements at their established stations. The number of stations eventually grew from roughly 40 to 80, spanning the coast from Louisiana to Texas.

Rabalais and her colleagues also dug into the history of nutrients, literally. By inserting tubes into mud from the bottom of the Gulf and slicing them up, they were able to date the different layers of sediment and identify amounts of carbon and nitrogen from decades earlier. That proved the Gulf had not always been low in oxygen.

“We didn’t just go out and measure oxygen on the bottom,” Rabalais said. “We did all kinds of things to piece together the story and develop the long-term dataset.”

A life of hypoxia research

Over time, the crew grew to include professors, scientists, students and volunteers from a variety of disciplines. Many have become familiar faces.

One was fellow oceanographer Eugene Turner, now a professor at LSU. A mainstay in hypoxia research from the beginning, he also became Rabalais’ partner, although she swore there was no romance on the boat. They married in 1988. Eventually, she would wear her wedding ring while replacing underwater monitors, the glint of gold sparkling in murky green waters, the fish nibbling her hair and mistaking it for seaweed.

Together, Rabalais and Turner worked to detail the effects of hypoxia in the Gulf, its link to nutrients and the source of those nutrients.

Her work at LUMCON offered Rabalais opportunities for professional growth, as well as moments of personal struggle. Public speaking used to make Rabalais quiver. During one lecture, Turner recalled, she shook so much she had to hold on to the lectern to stay steady. He even moved near the podium in case she fainted.

But with practice, Rabalais conquered her fear. By 1998, she was testifying before Congressional committees to tell legislators why they should be concerned about hypoxia. As a result, Congress decided that federal funds should be given each year to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to mitigate hypoxia.

“When we started out, she’d laugh at me. She’d say ‘Oh, you’re going to write a paper and change policy?’” Turner said. “But that’s what we do.”

As Rabalais’ dataset and publications grew, so did her authority and influence. She became executive director of LUMCON in 2005 and maintained the position until 2016. In 2012, she was awarded a MacArthur Foundation “genius grant,” and in 2021, she was elected to the National Academy of the Sciences, one of the most prestigious U.S. scientific societies.

Gulf’s dead zone caused by Midwest runoff

Rabalais’ research has documented most of what we now know about Gulf hypoxia. From about May to September every year, the Gulf develops the largest hypoxic zone in the U.S. Hypoxic conditions occur when an area of water has less than 2 milligrams of oxygen per liter of water. It usually means the death or flight of most living organisms in the area.

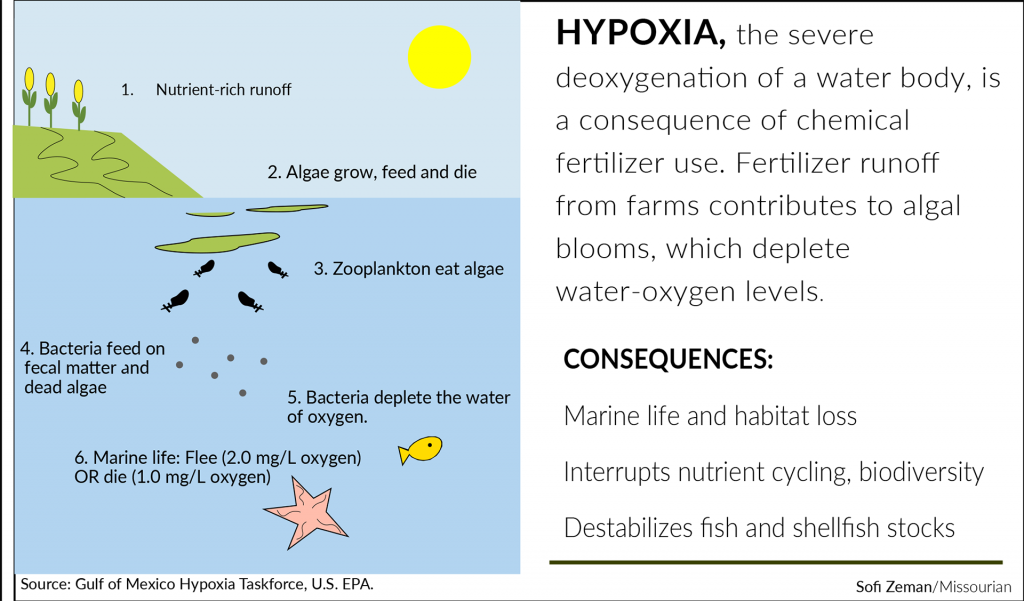

Hypoxia can occur naturally in water, but humans have worsened the problem since the 20th century. Nutrient runoff from farm fertilizer and other sources washes into rivers and streams, increasing nitrogen and phosphorus in waterways. Nutrients from states and provinces in the Mississippi River Basin wash into the watershed and into the Gulf in the spring and early summer. The freshwater with excess nutrients lies on top of the Gulf saltwater and spurs algal blooms. The algae eventually die and sink into the saltwater below, using up the oxygen supply.

Matt Rota, the senior policy director for the advocacy group Healthy Gulf, said addressing nutrient pollution is not only important for the Gulf, but also for its upstream neighbors.

“The things that we’re doing to cause the dead zone are also causing us to have less healthy soil and causing our drinking and recreational waters to become polluted,” he said.

Hypoxic conditions in the Gulf also shrink the available fishing area for the shrimping industry, increasing competition among fishers. Third-generation Louisiana commercial fisherman Thomas Olander said he advised his son to get out of the business, but his passion for fishing drove him back to it.

“I’d like to see my son stay in this business because my daddy did it and his daddy did it,” Olander said. “It’s sad that this industry could stop with my generation.”

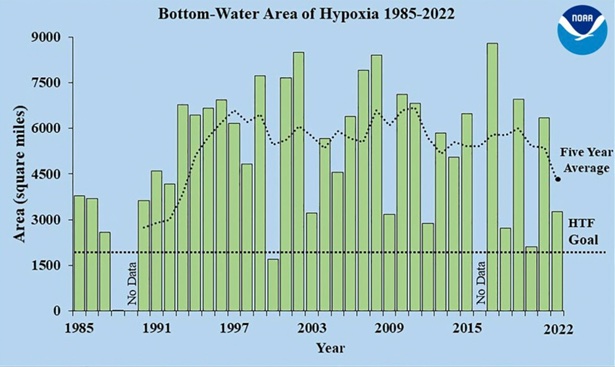

The hypoxic monster stretched across about 3,275 square miles of the Gulf in 2022. It was smaller than the previous year’s, mostly due to lower discharge from the Mississippi River. The trendline of the area’s growth has largely increased over time. The five-year average size is still more than two times larger than the 2035 task force goal.

“We’re not on track,” Rabalais said regarding the goal. “I keep saying there’s no social will.”

Every June, scientists issue a prediction for the size of that summer’s dead zone. This year’s announcement is slated for June 6. Rabalais and Turner will release their own press release around the same time.

Fertilizer and agribusiness

Since the 1950s, the amount of nitrogen in the Mississippi River watershed has tripled, and the amount of phosphorus has also increased, in part from fertilizer applied in Midwestern states along the Mississippi River Basin.

Congress exempted agriculture from the Clean Water Act of 1972, leaving responsibility for controlling nutrient pollution to individual states. This restricts the EPA’s ability to limit nutrient runoff from non-point sources like farms. The result is multiple federal- and state-funded efforts to reduce nutrients through voluntary programs for farmers, like rotating crops to enrich the soil naturally without fertilizer. But those efforts have not yet met goals to dramatically reduce the size of the dead zone.

“Trying to solve a problem of this magnitude through individual actions, you can’t find an example where that has ever been done,” said Chris Jones, a recently retired hydroscience and engineering researcher at the University of Iowa. Jones recently published a book about the link between agriculture and water quality and has his own blog on the same topic.

Jones argued the responsibility of reducing nutrient runoff should not rest solely on farmers, but on the agriculture system itself. Like all human beings, he said, farmers act in their own self-interest. Since there is usually no financial incentive from states to reduce their fertilizer application practices, farmers often opt out of alternative practices.

For Rabalais, persistence is the name of the game. She believes we shouldn’t discount the role of the individual, either. By changing diets, Rabalais said, people can signal their opposition to inappropriate fertilizer use. She eats less meat and avoids ethanol fuel to lessen her personal impact. And she stays positive, despite the size of the problem.

“I try to maintain my optimism that good efforts can produce good results,” she wrote in a 2021 reflection on her work. “It is more satisfying than dwelling in pessimism or fear of failure.”

A new era

Nothing tasted better than ice cream on the bow of the Pelican after a week of 16-hour shifts.

With the open, sunlit blue waters lapping at the hull, marine biologist Cassandra Glaspie felt a sense of accomplishment washing over her and her crew. As they turned the boat back toward the Louisiana coast, the feeling followed them in the form of bottlenose dolphins, gently dipping in and out of the Gulf.

It was 2020, and Glaspie had just led her first research cruise measuring oxygen levels in the Gulf. The trip was supposed to be a chance for Rabalais to show Glaspie the ropes. But just a few days before the voyage, Rabalais had to pull out due to an injury, leaving her available by phone only. Glaspie wasn’t worried.

“All of the crew of the Pelican know exactly what to do, because they’ve done this many, many years,” she said. “It was a well-oiled machine.”

Glaspie studies benthic organisms, creatures that live in bottom waters. After finishing a postdoctoral program in Oregon studying hypoxia, Glaspie became a professor in the same LSU department as Rabalais.

The key turning point of her career happened in Mobile, Alabama, when Rabalais pulled Glaspie aside at a university function.

“She said, ‘I put a lot into this hypoxia cruise, but I can’t do this forever, so I’d like you to consider taking it on as part of your research program,’” Glaspie said. “That will always, I think, remain a really wonderful memory.”

As she takes on her new role, Glaspie finds Rabalais’ mentorship valuable in navigating the world of science and politics. She said Rabalais has taught her how to play the long game, avoid knee-jerk reactions and develop relationships with everyone in her network, regardless of opinion.

“Nancy handles a lot of the political field with grace and keeps her intellectual integrity,” she said. “It makes her very respected, and so she’s been able to get a lot done because of that.”

In addition to heading the annual research cruise and some studies, Glaspie is taking on portions of Rabalais’ lab and deciding what the future will hold. She wants to return to continuous monitoring of hypoxia in specific areas, a venture that Rabalais once led, and update monitoring technology. She also has interest in starting an internship for students from underrepresented groups, including farmers’ children.

But moving forward, funding for other research and new programs may be a challenge.

NOAA provides funding for the research cruise to measure oxygen in the water, which maintains the dataset over time. However, continuing long-term study of factors contributing to hypoxia, like the distribution of nutrients, requires additional funding.

“There’s more to this research than just the oxygen,” Glaspie said. “Nancy and I have been trying to find ways to get the rest of it funded.”

David Scheurer, an oceanographer for NOAA’s National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science said future funding from the organization is hard to predict.

“NOAA in a large picture is supportive of continuing to monitor the dead zone,” he said. “We will try to do that however makes the most sense for a given year.”

On the bow of a smaller research vessel named Acadiana, funding and fertilizer seem far away in the peaceful wake of the bay. But their impacts are found within the tiniest organisms squirming through the mud.

As Glaspie reels up a sample of mud from the bay, the slight odor of sulfur mixes with the salty scent of the water. She digs a finger into the black and brown sediment and finds a worm called a Capitellid, which doesn’t need a lot of oxygen to survive.

“These are the weeds of worms,” she said, pointing to the small, long and thin creature. Combined with a lack of other species in the area that require more oxygen, their presence can be an indicator of hypoxia.

In a way, Glaspie has a lot in common with the critter. Despite the challenges of the dead zone, she’s here to stay, carrying on Rabalais’ legacy.

Making progress

Back on shore, Glaspie joins Rabalais in the lab. They laugh and chat about their remaining work, taking a few moments to peer into a container holding a small squid caught on the boat. Hanging above them is a framed painting from the 2007 cruise, featuring handmade icons like underwater sensors and divers in scuba gear.

The work is never finished, but Rabalais is hopeful for the future.

“I would like to see a healthy gulf,” she said. “We can never go back where we were, but we can make progress.”

This story is part of The Price of Plenty, a special project investigating fertilizer from the University of Florida College of Journalism and Communications and the University of Missouri School of Journalism, supported by the Pulitzer Center’s nationwide Connected Coastlines reporting initiative.

Read Next: Your money and the climate are up for debate in this year’s farm bill

The Price of Plenty

The Price of Plenty