The worries over PFAS that began downstream from chemical plants now stretch across the country, including in Florida’s waters.

By Jordyn Kalman

Emily Donovan had no idea what “PFAS” were until the news broke that her drinking water in Brunswick County, North Carolina, had been contaminated with the chemicals.

The Chemours Company, a spin-off of DuPont, had been dumping the so-called “forever chemicals”—the technical names are per- and polyfluoroalkyl, or PFAS—into the Cape Fear River. More than 200,000 residents depend on the river for drinking water.

Communities downstream of the Fayetteville plant were potentially exposed to more than 250 different types of PFASs, Donovan said. The chemicals are associated with a range of negative health outcomes from endocrine disruption to cancer, according to the National Toxicology Program and National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Donovan and her neighbors believe their exposure led to the development of a thyroid cancer cluster among residents.

“We really still don’t have a complete picture of just how much we were exposed to.”

–Emily Donovan, Clean Cape Fear

“We really still don’t have a complete picture of just how much we were exposed to,” said Donovan, who works full-time on PFAS and safe drinking water through the advocacy group she cofounded, Clean Cape Fear. “So that was really shocking and disturbing that a company with such a high visibility was doing this in our backyard.”

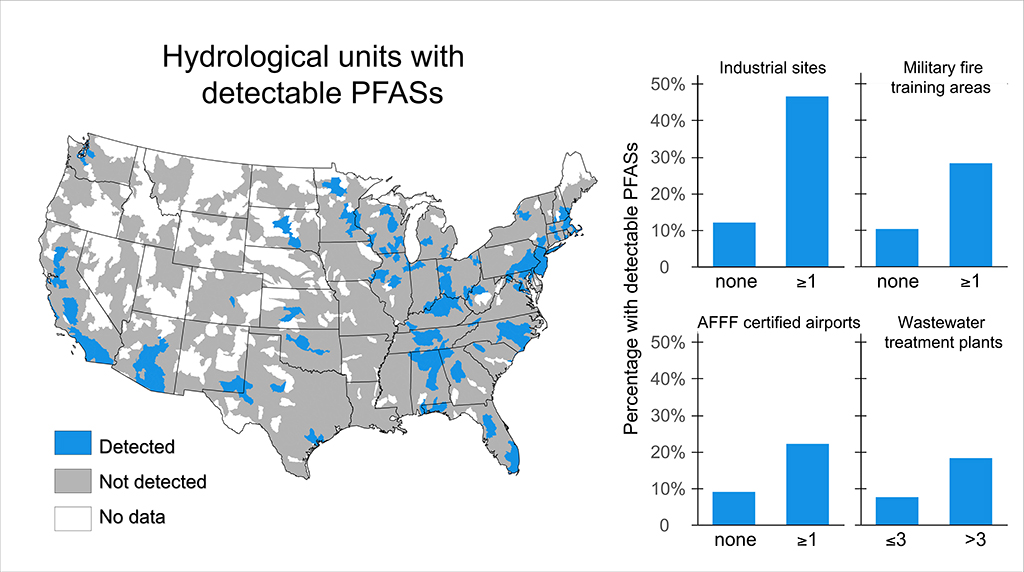

The worries that began in communities downstream from chemical plants now stretch across the country, including in Florida. PFAS are being found in significant concentrations where they were used, including in military bases; airfields and airports; and firefighting practice areas. Results of wider state testing by University of Florida’s Center for Environmental & Human Toxicology are expected later this year.

What are PFAS?

PFASs are a family of thousands of chemicals produced commercially since the 1950s, with many still used today. They can be found in manufacturing processes, industrial products, firefighting equipment and consumer goods including food packaging, cookware, upholstery, carpets, cosmetics, paper, paint, pesticides, architectural products and much more.

They resist heat, water and oil. What make them attractive for manufacturing also makes them harmful to humans.

They were nicknamed “forever chemicals” because they do not break down naturally over time. This allows PFAS to easily migrate through the environment, contaminating everything from drinking water to food, soil, dust and wildlife.

Many companies that had been using PFAS in their products have phased it out. But PFAS are still ubiquitous.

Some companies may still be producing PFAS or distributing existing stocks. The chemicals are still present in many imported goods. And manufacturers have begun replacing PFAS with structurally similar and largely untested chemicals that may pose the same safety hazards.

The persistence and mobility of PFAS, combined with decades of production and distribution, has created concerns about human health risks.

PFAS Health Risks

Elevated levels of PFAS in the body have been linked to “a variety of specific adverse human health outcomes,” Linda Birnbaum, director of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the National Toxicology Program, said in a Congressional hearing on the federal response to the chemicals. They include “immune system dysfunction, endocrine disruption, altered obesity profiles, impaired child development and cancer,” she said.

Still, many health and environmental risks remain uncertain. CDC studies show that nearly every American’s bloodstream contains PFAS. The chemicals build up over time in the body with every instance of exposure.

The Environmental Protection Agency has set a health advisory level for PFOA and PFOS, two of the most dangerous and well-studied forever chemicals, in drinking water at 70 parts per trillion, suggesting a person who consumes this much over a lifetime is at greater risk of these adverse health effects.

But there is growing evidence that PFAS are risky at much lower levels. Emails disclosed in early 2018 found that the EPA suppressed a scientific assessment from a federal health research agency that recommended a level 7-10 times lower than the agency’s health advisory.

A recent study by the Harvard School of Public Health and University of Copenhagen found that exposure limits set by the EPA and other agencies for PFAS in drinking water appear to be 100 to 1,000 times too high. The Environmental Working Group, a non-profit, non-partisan organization dedicated to protecting human health and the environment, has proposed a stricter standard for PFAS at 1 part per trillion based on these findings.

“Other toxins are measured in parts per billion, and PFAS are measured in parts per trillion, which is like a drop in an Olympic sized swimming pool,” Donovan said. “They’re very toxic in small doses.”

PFAS in Drinking Water

Drinking water is one of the most common routes of exposure. PFAS have so far polluted the tap water of at least 16 million people in 33 states and Puerto Rico, as well as groundwater in at least 38 states, according to the EWG.

In Florida, there have been 121 reports of PFAS found in ground and drinking water sources. However, because PFAS contamination has been tracked in the state for only a few years, and not widely, the number of contaminated sites is suspected to be larger.

Another Harvard study revealed that public drinking water supplies for six million Americans exceeded the federal safety levels. Lead author Xindi Hu said the actual number may be higher because government data for levels of the compounds in drinking water is lacking for almost a third of the U.S. population.

The environmental chemist Elise Sunderland at the Chan School said what’s known about PFAS health effects suggests the safe drinking water levels should be much lower than the EPA advisory. But EPA has not yet established a national regulatory standard or requirement for nationwide testing.

“The Environmental Protection Agency has utterly failed to address PFAS with the seriousness this crisis demands, leaving local communities and states to grapple with a complex problem rooted in the failure of the federal chemical regulatory system,” EWG President Ken Cook said in a press release.

PFAS in Vulnerable Communities

While everyone is exposed to PFAS to some degree, vulnerable populations such as low-income people and communities of color often bear the economic and biological burden of pollution.

In one study, higher income is associated with higher PFAS concentrations, possibly due to exposure from foods and household products. However, lower-income populations have been found to be disproportionately exposed to contamination sites.

Analyzing data on non-military site contamination, the Union for Concerned Scientists found disproportionate numbers of low-income households and people of color living within five miles of reported PFAS contamination.

Black, Latino, and Indigenous communities, as well as low-income families, are more likely to live near industrial sites, chemical manufacturing plants, and waste management areas where pollution accumulates compared with white, affluent communities.

Economic status also affects people’s ability to fight PFAS contamination, Donovan says. Language and financial barriers make it harder to raise awareness and invest in solutions in vulnerable communities. More affluent groups with access to health care are better able to recognize medical problems in the early stages.

“Everybody, everybody is drinking the same contaminated water,” Donovan said. “But if you have a higher level of income and a higher level of education, you can immediately protect yourself.”

“People are sort of waking up to the public health threat and are acting accordingly and are demanding more of their elected officials.”

–Erin Fitzgerald, Earthjustice

Policy Solutions

Without federal leadership, states have scrambled to regulate PFAS, which has led to a patchwork of standards across the country. Michigan, New York, New Jersey, Vermont, California, Massachusetts, and Minnesota have stricter PFAS limits than the EPA.

Action to address PFAS contamination is underway in multiple forms: proposed legislation, federal and state regulation, and litigation. Clean Cape Fear has co-sponsored a national petition asking the EPA to classify PFAS as hazardous substances under the Superfund law, which provides federal funding to clean up hazardous-waste sites as well as accidents, spills, and other emergency releases of pollutants into the environment.

The hazardous substance designation would require polluters to pay for the contamination they created and provide federal funding to clean up hazardous-waste sites, Donovan said. Right now, millions of taxpayer dollars are being spent to upgrade water treatment plants and clean contaminated water supplies.

Erin Fitzgerald with Earthjustice, a non-profit environmental law organization, said that while governments are facing lawsuits and public pressure to regulate PFAS, concrete change will take time and patience. “As far as how that policy is going to play out, I think it’s still so unclear,” Fitzgerald said. “I think the future of environmental regulation is still a big question mark.”

But she said real progress is underway as people come to understand the risk of PFAS.

“Part of advocacy is, of course, winning in court, but another part of it is the court of public opinion,” Fitzgerald said. “People are sort of waking up to the public health threat and are acting accordingly and are demanding more of their elected officials.”

Read Next: Part 2 – Indestructible

Forever in Florida

Forever in Florida