Fertilizer companies cash in while farmers struggle

Claims of market manipulation drive national concern over industry consolidation

By Noah Zahn

On a small vegetable farm in Georgia, Shad Dasher used to grow watermelons every year.

Last year, he didn’t plant any.

Dasher, 56, says it was because of elevated fertilizer prices. Like many of his fellow farmers, Dasher is finding it hard to stay afloat. “The American public just doesn’t understand what kind of beating our group [of farmers] has been taking over the years,” he said.

Fertilizer companies are enjoying the highest profits on record as farmers and others who rely on fertilizer have no choice but to spend more. Although fertilizer prices have fallen from their all-time high in March 2022, when they spiked up to 3.5 times higher than two years before, the commodity is likely to remain costly for some time, continuing to squeeze the food production system.

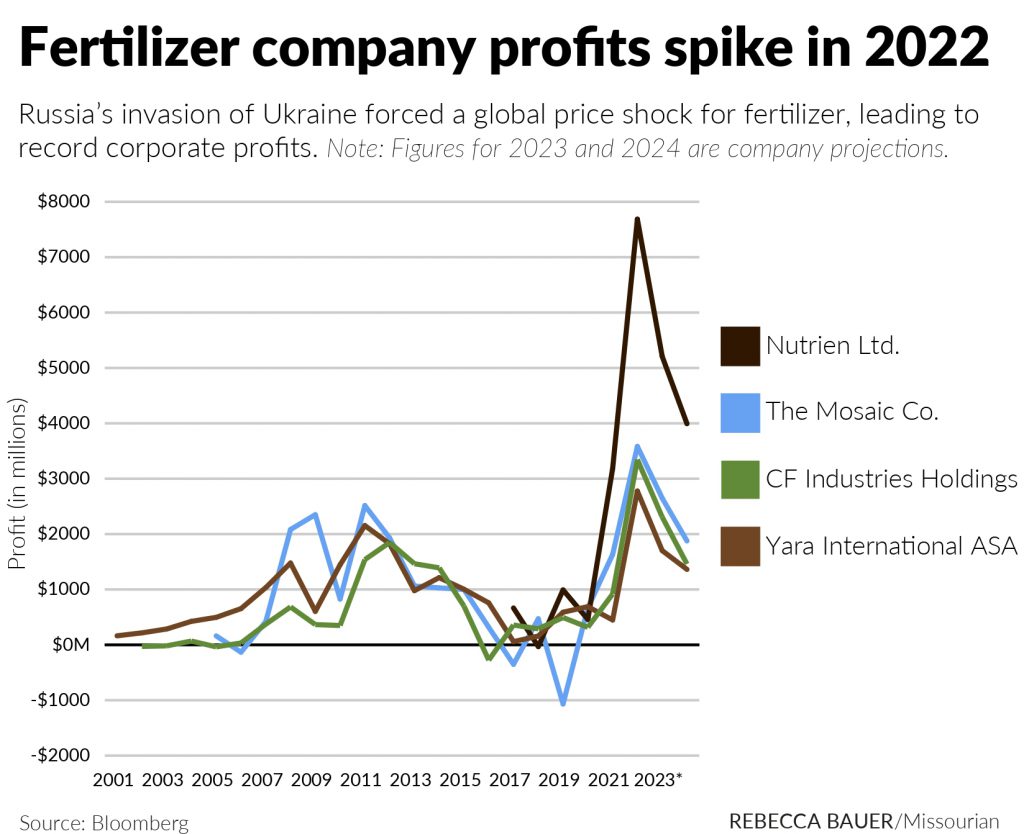

Meanwhile, the fertilizer industry has yielded record profits. Canada-based Nutrien Ltd., the world’s leading producer of potash fertilizer, saw profits increase 1575% between 2020 and 2022 to $7.7 billion. Tampa-based The Mosaic Co., one of the largest U.S. producers of potash and phosphate fertilizer, made $3.6 billion in net earnings in 2022, a 438% increase from 2020. CF Industries, an Illinois-based fertilizer company, made $3.2 billion in 2022, a 955% increase from 2020.

The eye-popping figures have heightened concerns about consolidation in the fertilizer industry, even as the Biden Administration moves to boost domestic fertilizer production.

When asked for comment, Mosaic said in an email that the fertilizer business is cyclical and thus has volatility in prices.

CF Industries did not respond to requests for comment. Nutrien did not provide a statement by press time.

Why is the price of fertilizer so high?

There are a few clear reasons for the recent record fertilizer prices. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 caused disruptions to the supply chain and labor shortages that hindered production of natural gas, a major ingredient in fertilizer.

Then came a series of natural disasters, such as the February 2021 deep freeze in Texas, which froze natural gas wells and drove up demand for residential heating. In August that year, Hurricane Ida disturbed natural gas and fertilizer production in the Southeast.

Another factor was a reduction in exports from China, the world’s leading producer of phosphate, a chemical element that is a key ingredient of fertilizer.

The war in Ukraine further tightened the market as Western countries sanctioned Russia, the world’s top fertilizer exporter. Disruptions in natural gas flow from Russia led to spikes in European natural gas prices and forced several European fertilizer plants to close or cut output.

Even low water levels on the Mississippi River contributed to price increases, as it limited the amount of fertilizer that could be shipped by barge.

“There were a myriad of reasons why we were seeing this big run up in fertilizer prices. It’s not just one thing. It was literally a whole menu of things that were seemingly going in the wrong direction if you were looking to obtain fertilizer,” said Chad Hart, an agricultural economist at Iowa State University.Several of these factors are referenced in a study Hart co-authored that was hailed by The Fertilizer Institute for providing “the best analysis data will allow to date.” But some argue the study omits a large factor of the price increase: market power as a result of consolidation.

Is the fertilizer industry manipulating the market?

Farm Action is a Missouri-based nonprofit organization that advocates for competitive food and agriculture systems across the United States. Co-founder Joe Maxwell believes consolidation in the fertilizer industry has led to market manipulation.

Since 1980, the number of fertilizer firms in the United States has fallen from 46 to 13. In 2019, just four corporations represented 75% of total domestic fertilizer production: CF Industries, Nutrien, Koch, and Yara-USA, according to Farm Action. And just two companies supply 85% of the North American potash market: Nutrien and Mosaic, according to the Federal Trade Commission.

“These companies took advantage of their dominant position in a marketplace and increased commodity price to the farmers in an effort to price gouge and extract all the wealth that they could from that supply chain at the very roots: fertilizer,” Maxwell said.

In 2021, the United States imposed tariffs on fertilizer imports from Morocco and Russia following petitions from Mosaic and CF Industries.

Growers widely derided the move. A letter from the National Corn Growers Association to Mosaic accused the company of “irresponsible” practices that “manipulate the supply curve” and “dictate price to farmers.” Later that year, Farm Action wrote a letter to the Antitrust Division of the Department of Justice accusing the fertilizer industry of using its “monopoly power” to fix prices and requesting an investigation.

A week later, Sen. Chuck Grassley, R-IA, submitted an additional letter to the DOJ requesting investigation. As of mid-May 2023, the DOJ has not announced an investigation.

Mosaic said in an emailed response that since the countervailing duties took effect, foreign producers importing fertilizer into the North American market has increased, and by extension, made the market more competitive.

In a company Q&A, a Mosaic official, Andy Jung, said that the countervailing duties are not the reason for price increase and said that the current market is not driven by “merely by a ruling for fair trade.”

President Joe Biden issued an executive order in 2021 promoting competition in the economy, including the agriculture sector and the fertilizer industry specifically. “Consolidation in the agricultural industry is making it too hard for small family farms to survive,” the order reads.

In response to the order, the USDA collected comments from agricultural producers on competition, access to fertilizer, and supply chain concerns. From more than 1,600 responses, 72% described concerns about the power of fertilizer manufacturers and 62% described what they saw as unfair price-setting practices.

One farmer commented to the USDA: “The excessive price increase of fertilizer appears to be fueled by greed within the small group of fertilizer manufacturers.” Another farmer said: “The price of fertilizer today is set by the producers depending on what the price of corn and beans happens to be.”

CF Industries replied to the USDA by comparing fertilizer to food commodities.

“Nitrogen fertilizers are internationally traded commodities, like the corn, wheat and other crops they feed,” the company said. “Their prices are influenced by global supply and demand factors, as well as domestic and local conditions.”

While the study from Iowa State University does acknowledge market consolidation, it dismisses it as a factor of price increase.

Hart sees the consolidation, but he said that to prove market manipulation, you have to be able to observe the market over a long and stable period of time, which has been difficult amid recent events.

“You just can’t separate out what’s happening and whether there is a competition problem in this market or not,” Hart said.

While all many factors have made the ingredients for fertilizer more expensive, the increase in profits is disproportionate to the increase in production costs – basically, they’re making a lot more money than they’re spending. In 2022, Nutrien’s cost of goods sold increased by 24% compared to the year prior; however, its profits were up 142% from 2021. CF Industries saw its profit increase by 212% in 2022, while the cost of manufacturing and sales was only up 28%. For Mosaic, profits were up 120% in 2022, but cost of sales only increased by 46%.

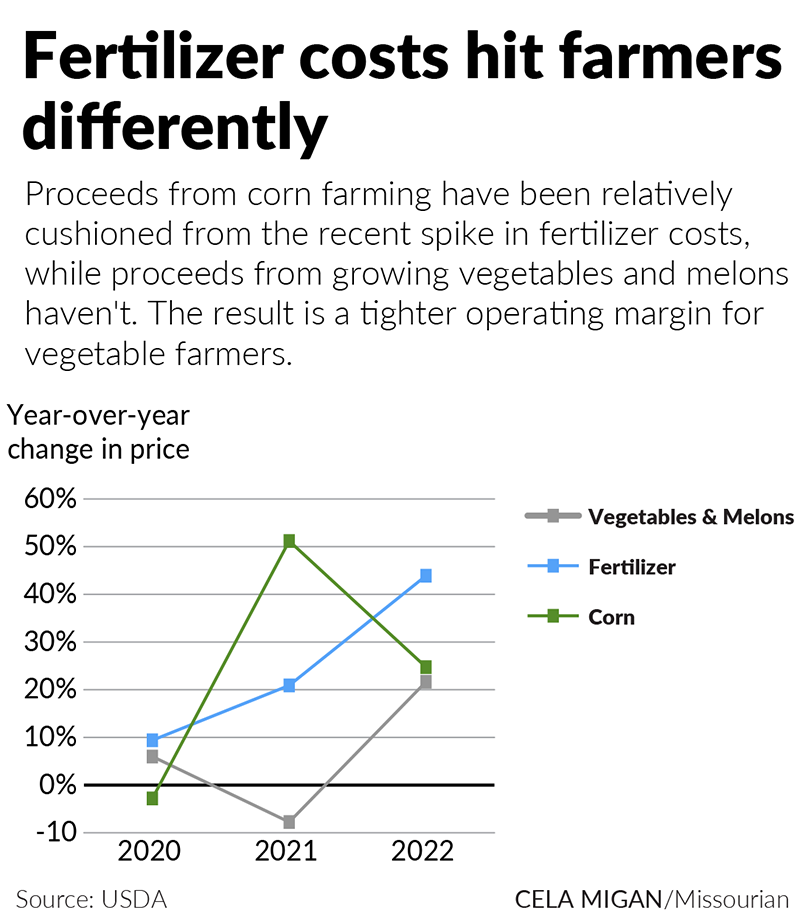

Although corn farmers enjoyed the highest corn prices on record in September 2022, their profits were offset by increased fertilizer prices.“These [fertilizer] corporations are well aware of their leverage and have used the cover of consecutive global crises to raise prices far beyond those demanded by necessity,” Farm Action said in a comment to the USDA.

Who is hit hardest by fertilizer prices?

While record fertilizer prices have translated to record profits for the fertilizer industry, small farmers, business owners and rural communities struggle to pay bills.

Gary Hamilton owns a small business in northeast Missouri called Frankford Farm Supply, where he sells fertilizer and farming equipment. He started the company about 30 years ago.Hamilton’s store is down the road from one of the many corporately-owned Nutrien stores that are scattered across rural America. Hamilton said that Nutrien’s prices are lower and he just can’t compete as a small family-owned business with less than 15 employees.

When fertilizer prices go up, Hamilton’s credit limit doesn’t. This means he may not be able to serve as many customers as he used to, and those customers have to turn to other stores for their fertilizer supply.

“Because of the high prices, I actually lose business. And when I lose business, then I have less money to pay for health insurance, fuel, salaries, wage increases, day-to-day things that businesses need to survive,” Hamilton said.

Do fertilizer prices drive food insecurity?

Global experts also worry about how the high cost of fertilizer affects rising food prices and growing global food insecurity.

John Baffes, a senior agriculture economist for the World Bank, said that fertilizer is an important input to food commodity production, especially in less-developed countries.

The International Monetary Fund’s World Economic Outlook in October 2022 said that a 1% increase in fertilizer prices boosts food commodity prices by 0.45%. Experts say the connection between fertilizer price and food inflation is smaller in the U.S. Alexis Maxwell, a fertilizer analyst for Bloomberg Intelligence, said there is not a strong correlation between the two.

However, even small increases add to the burden of the food-insecure. Prices for food at grocery stores increased 13.5% between August 2021 and August 2022, the largest 12-month percentage increase since 1979, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Many factors account for the increase, such as higher fuel costs for transporting food.

Katie Adkins, director of marketing and communications at The Food Bank for Central & Northeast Missouri, says that the food bank is serving about 30% more people now than it was last year.

Adkins also said the food bank is currently spending three times as much on food as it was before the pandemic due to higher prices and fewer donations. “In general, we are seeing fewer donations from some of those big companies, simply because people are cutting back on their production,” Adkins said.

What’s next?

Despite these concerns, it will be hard to lessen dependence on fertilizer anytime soon. It’s essential for supporting the world’s population.

“If we did not have fertilizers, the earth’s population will be not 8 billion but will be 4 billion,” Baffes said.

Farmers and small business-owners may complain about fertilizer prices, but they will continue to pay for it, Hart says, because their business depends on it.

Experts say fertilizer prices may remain high for some time, but they are expected to fall – eventually.

“As farmers have pulled back, the lesser demand has allowed some of our supplies to rebuild,” said Alexis Maxwell, the Bloomberg analyst. “Prices are falling. So it’s good news.”

This story is part of The Price of Plenty, a special project investigating fertilizer from the University of Florida College of Journalism and Communications and the University of Missouri School of Journalism, supported by the Pulitzer Center’s nationwide Connected Coastlines reporting initiative.

Read Next: Fertilizer’s greenhouse gas emissions add up

The Price of Plenty

The Price of Plenty