Inhabited and uninhabited, barrier islands move. They will need fortification to survive predicted increases in sea level rise.

The shores of Cedar Island, Virginia, are animated with movement. The ocean laps the sand and pulls it out to sea. The marshland on the back side of the island hums with the sounds of birds and fish flying from the warm, shallow water to avoid being someone’s next meal. All this stirring is observable, ordinary and easy for boaters and other ocean lovers to understand. But they may not know the island is moving. Literally.

Erosion from increased storm activity and the second-highest rate of sea level rise in the United States have made Cedar Island ground zero for barrier island movement. Waves are hitting the island harder and taking sand out to sea, while winds are blowing sand off the island. The wave and wind action leaves the island vulnerable and malleable. Over 15 years, Cedar Island has shifted to open a jetty and close it back up; from a solid island to two smaller islands; and back again. And this is only the beginning, says Christopher Hein, an associate professor of coastal geology at the Virginia Institute for Marine Science.

“Even if sea level rise stopped increasing today, the islands are still going to continue to migrate, and migrate faster,” Hein says.

Cedar Island is uninhabited by people. But that doesn’t make its migration any less concerning to humanity. Barrier islands are the first line of defense against harmful storm surges, Hein says, creating a wall between intense wave action and the mainland. When the islands move, the mainland loses natural protection and entire ecosystems.

Inhabited and uninhabited, barrier islands move. Fortification can help them survive predicted increases in sea level rise. The strategies for building them up are as unique as the islands themselves. Also like the islands, some strategies are natural and some built. On Cedar Island, Hein’s research team is working to bolster natural resiliency by building up salt marshes on the backsides of barrier islands.

Saltmarshes essentially catch the sand that winds and waves erode off barrier islands. The marshes allow the sand to build up, fortifying the island to keep up with rising seas. Without a salt marsh on the back of the barrier island, Hein says, any sand vanishes. Barrier islands still move.

While such natural strategies can stave off migration of uninhabited islands, developed islands need solutions that include the built environment, says Mohamed Dabees, vice president of Naples-based Humiston and Moore Engineers. Dabees was drawn to Southwest Florida for its great number of barrier islands. The 200-mile stretch of islands from Pinellas County south to Collier County is not only Dabees’s study area, but his backyard.

“Barrier islands are one of my passions,” Dabees said. “The dynamics of barrier islands are a good example and lesson to follow on how we can learn from and work with nature towards a more resilient approach to dealing with climate change and potential sea level rise.”

Dabees believes that the best approach to building resiliency is to create structures that work with nature, not against it. That’s easier said than done when so much of Florida was built mid-century when the approach was to fight against nature.

That was the case on Marco Island, which Dabees studied to determine nature-based fortification options. The southwest Florida barrier island was still largely wild until the Mackle Brothers purchased the land for $7 million in 1962, according to the City of Marco Island. By 1965, the island had been developed according to a master plan and by 1968 the population skyrocketed to over 1,000 people. Today, it is home to 16,000.

“When this island was developed 50 to 70 years ago, our coastline did not have the same shape,” Dabees said. “As the islands shift, the structures stayed in place and have more direct interaction with the water than they did when they were built.”

While hindsight is 20/20, Dabees believes past mistakes can help inform a better future. Structures must be built and retrofitted with long-term trends in mind. Islands are moving, sea levels are rising and storms are getting more intense. Structures built today on barrier islands must include a lower level that can flood—working with water rather than fighting water like the Mackle brothers. Armoring barrier islands with seawalls and beach berms will only cause greater disruption, Dabees says.

On the opposite coast of Florida at Hutchinson Island, a narrow barrier island stretching 23 miles through St. Lucie and Martin counties, engineers are focused on stabilizing dunes and beaches. The island is home to picturesque beaches, and families whose connections on the island date back to the early 20th century. Today, it is also home to more than 15,000 residents and a booming tourism industry. Yet climate change is already having negative impacts, from heavy rainfall and flooding to severe coastal erosion that has wiped out protective dunes altogether on some parts of the island.

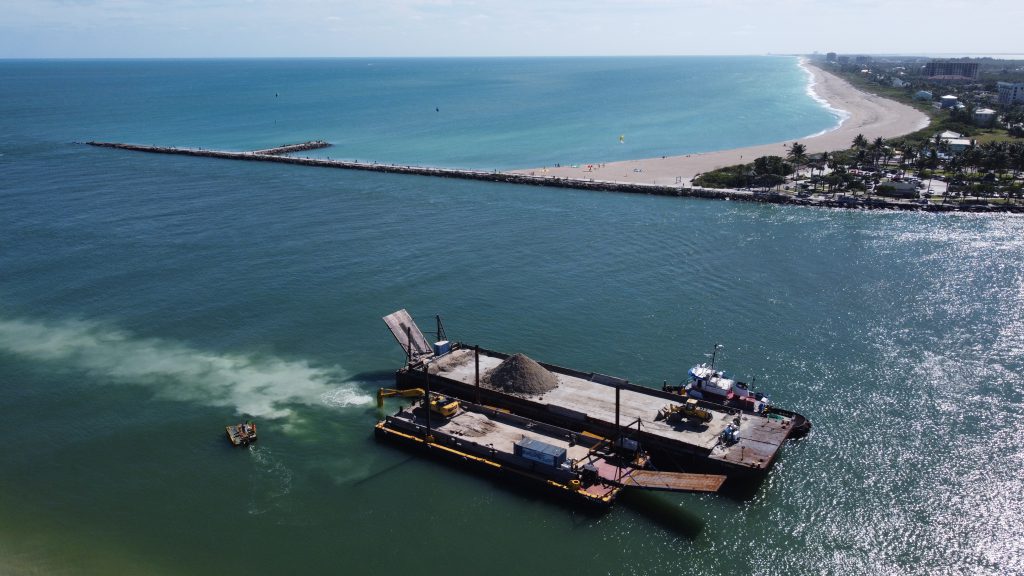

On the northern tip of the island, Martin County is building a barrier beneath the dunes at Bathtub Beach reef to defend them from wave action, and elevating MacArthur Boulevard to prevent its loss in storms. To the south, St. Lucie County has received approval for the long-awaited South County Federal Beach Renourishment Project, which engineers hope will help shore up the beach and dune system for the next half-century.

“Since this is a federal beach project, it took 20 years for it to actually come to fruition,” says Josh Revord, senior coastal engineer for St. Lucie County

Revord sees beach renourishment as a form of “soft-built resiliency.” Engineers will spread 400,000 cubic yards of sand along a 3.4-mile stretch to restore the dune system to what it was a decade ago. The project aims to save more than $1.2 billion in assets, not including roadways and infrastructure such as power and plumbing.

“The amount of material that we’re placing is really an attempt to give Mother Nature the resource she needs to make adjustments and provide additional protection during storm events,” Revord says. Both counties also have climate resilience groups at work on plans to try and keep ahead of rising seas. “South Florida has experienced and continues to experience more significant impacts because of rainy day flooding and title issues so they are really leading the conversation on what it means to be resilient,” Revord said.

Every solution is on the table, from mangrove restorations to sand-trapping fences buried under the dunes. Scientists, coastal engineers and environmental planners who work on barrier islands say they are essentially in a race against time and rising seas.

“We cannot stop erosion and sea level rise permanently,” says Hein. “We can try to slow it and buy more time for permanent solutions, but that’s where the conversation needs to be.”

Structures on Marco Island are already poking out into the Gulf of Mexico; many on Hutchinson Island slowly inching toward the Atlantic. The best solutions for each barrier island will be unique to its geology and geography, its tides and vulnerability—and its rate of movement, now hastening with each storm.

Revord, Dabees and Hein all warn that without action, structures, and the islands themselves, will continue to wash into the surrounding seas. The issue will no longer be how we make barrier islands resilient, but whether we can even live on them at all.

“If we don’t intervene in a reasonable time, then we will allow a feature to basically collapse and no longer exist,” Dabees said. “Then we end up with an unstable future.”

Living on the Edge

Living on the Edge