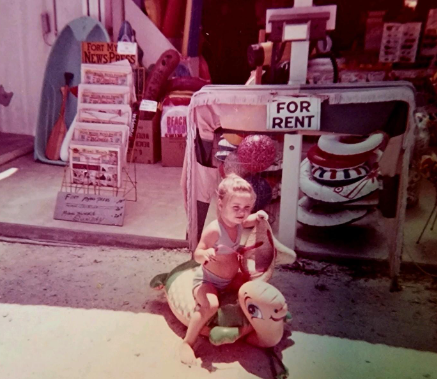

Sandy toes, striped swimsuits and surf boards. The Sanders sisters’ childhood in Fort Myers evoked an endless summer.

When they weren’t sitting in the backseat of their mom’s light green Ford Maverick helping her toss newspapers, Kimberly and Kathy spent time with their grandmother, the owner of Edna Mae’s Surf Shop on Fort Myers Beach.

“She had it down at what we call ‘Times Square,’” Sanders said. “It was a touristy shop, you go in there and buy coconut heads and silly things.”

The shop changed hands over the years but stayed true to old Florida beach nostalgia. Times Square, with its colorful clock and painted brick walkways, remained a favorite place to pick up vintage T-shirts or sip a mojito at a palm-shaded café. But today, the beach shop, its neighbors and the iconic Times Square clock no longer stand. They were destroyed along with thousands of other businesses and homes when Hurricane Ian ripped through Southwest Florida in September 2022.

After hitting Cuba as a Category 3 hurricane on Sept. 27, Ian gained strength over the warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico. On Sept. 28, the monstrous Category 4 hurricane struck southwest Florida’s beloved barrier islands including Fort Myers Beach, Sanibel, Captiva and Pine Island, the largest island on Florida’s Gulf Coast.

Six months later, those islands are still in various stages of clean-up and rebuilding. But whether they can retain their character of mixed-income homes and vintage beach vibes, especially in a time of climate change, is far from certain.

The largest U.S. population on barrier islands

Florida is home to the most extensive system of barrier islands in the United States, encompassing a third of the nation’s barrier shoreline running along the Gulf and Atlantic coasts. (Rocky cliffs and shifting tectonic plates along the Pacific Coast prevent barrier islands from forming there.) Florida also has the largest population of people living on barrier islands of any state in the nation, with hundreds of thousands inhabiting the vulnerable, shifting landscapes. The risk has long been worth it for families like Sanders’. But Hurricane Ian — and the science that climate change can make storms more severe — is changing that calculation.

Sanders, 61, now lives in Lehigh Acres, about 30 miles inland from Fort Myers Beach. She was a paramedic for almost 30 years with Lee County emergency services and now helps with cleanup efforts after disasters.

She said she is a descendant of the Blount family, who settled in the region during the 19th century. Since Ian, she has been working to aid recovery across the region she and generations of her family have called home.

“The amount of debris is unbelievable,” she said. “They’re going to be cleaning for a year.”

Sanibel may have a reputation for affluence — it is dotted with multi-million-dollar homes, after all. But before Ian, people of varying socioeconomic classes lived on both Sanibel and nearby Estero and San Carlos, the two barrier islands straddled by Fort Myers Beach.

Sanders helped clean up Periwinkle Park and Campground, a trailer park on Sanibel, in the wake of the storm. The people there lost everything, she said.

“These people, they’re not wealthy, but they pay their bills,” she said.

The risks of living on barrier islands threaten people of different income levels, though higher-income residents can more easily fortify their homes, evacuate and rebuild. Some people did not have the money to leave. Or maybe it was something they’d never consider, no matter what happened, not even a hurricane. Jennifer Sawyer’s parents, who live on Sanibel Island, fall into that category.

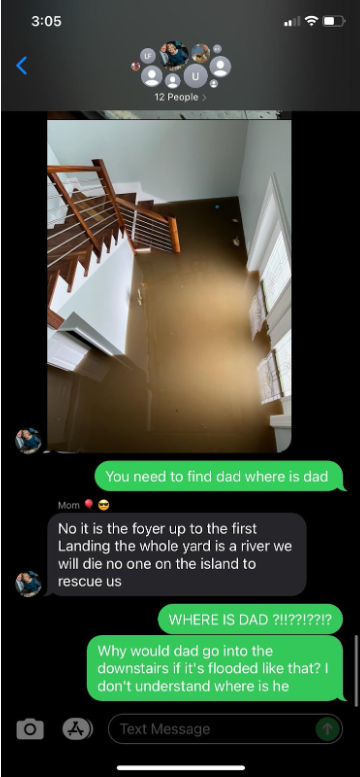

Sawyer, 27, said her parents decided to hunker down in their Sanibel home as Hurricane Ian approached. Sawyer’s dad likened the storm surge to the Colorado River with its violent rapids.

The first floor of their house flooded. Sawyer, who lives in Miami as she goes to school at Florida International University, lost contact with her parents.

“I started hearing, ‘two people dead on Sanibel,’” she said. “Oh my God, is this my mom and dad?”

Five frightening days later, Sawyer and her parents reunited.

Despite living through one of the worst storms in Southwest Florida history, Sawyer said her parents are working to fix the house and remain on the island even as fears of future storms loom.

“It’s just going to keep getting worse and worse,” she said, “but I just hope in their lifetime it’s not going to be too big of a deal.”

The growing risks of living on barrier islands

Scientists have flashed warnings about living on barrier islands for decades. “Barrier islands, particularly on the ocean side, have always been hazardous places for man,” researchers warned in the American Scientist in 1980. “Over the last several decades, however, this pattern of development has reversed, with most construction taking place dangerously close to the shoreline.”

“This trend stems from a strong desire to be near the water’s edge, even though that location clearly introduces serious risks to both life and property.”

Those risks have only gotten worse. As global temperatures rise, sea levels also rise due to melting ice sheets and glaciers and expansion of seawater as it warms. The higher seas worsen storm surge and erosion. Both encroach upon barrier islands — and can even eliminate them entirely. Climate change also shares a link with hurricanes because warmer ocean water and increasing moisture in the atmosphere can lead to more Category 4 and 5 hurricanes.

Storms and their effects, like flooding and erosion, are natural processes, which is also important to recognize, said John Jaeger, a geology professor at the University of Florida.

“It’s the built environment that has a hard time coping,” he said.

Jaeger works on coastal geology, which is becoming increasingly important as seas rise and damaging storms like last fall’s Ian and Nicole continue to threaten the state and communities near and on the water.

When barrier islands retreat over time or hurricanes and other storms pass through, the land cover changes are just nature running its course, Jaeger said.

In fact, hurricanes can entirely change the land cover on coastal landscapes, which is what researchers from North Carolina determined in a 2021 study.

The researchers analyzed land cover changes, such as marsh, vegetation and sand dunes, after Hurricanes Irene and Sandy on Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge, a coastal barrier island that constitutes a portion of the Outer Banks. The study highlighted the extent to which the hurricanes reshaped Pea Island.

Coastal ecosystems act as barriers — hence the name “barrier islands” — that protect ecological and human communities from storm and sea level rise, according to the study. The takeaway is that any efforts to preserve and rebuild coastal infrastructure must take into account the role of storms and erosion, said Elizabeth Sciaudone, a North Carolina State University engineering research professor who was one of the authors. For the barrier islands in Florida that continue to attract thousands of visitors and new residents each year, long-term planning is essential.

“When communities are doing these long-range plans, they really need to evaluate for themselves … what a resilient and sustainable future looks like,” Sciaudone said.

“How do you adapt to this compression of this coastal zone?” Jaeger asks. “There’s a lot of solutions people put out about trying to minimize the wave impact, how to deal with the rising sea level, all of those, but they still require some adaptations that a lot of people aren’t willing to put up with yet.”

Jaeger said the mentality is to “build back” rather than to retreat because that term is negatively connotated. For many people, it may signify a loss; a surrender.

Build back or retreat?

Chauncey Goss is one of the many who believe Sanibel will build back to its trademark old-Florida charm.

The former Sanibel city council member and current South Florida Water Management District Board chairman said his family lost their home to Hurricane Ian.

“I lost everything, and most of my friends did, too,” he said. “It’s tough, but you know, it’ll build back, we’ll be fine, and we’ll try and learn from it so that if the next storm that comes, we’ll be able to bounce back even quicker.”

This sentiment was evident on the island within weeks after the storm among both residents and government. Amid the rubble were signs spray painted with messages like “Still A Fisherman’s Paradise,” “Have Great Faith” and “Like A Good Pot Of Soup This Will Take Time.” The state finished emergency repairs to the Sanibel Causeway in 15 days; Lee County and federal authorities are now working to permanently repair the causeway and two other bridges at a total cost of more than $400 million.

Goss said Sanibel’s allure is that the island hasn’t changed — its history is preserved, making it a treasured time capsule.

“People came when their grandparents owned a place there, and then they keep coming back, and then they have kids, and it’s just generational,” he said. “A lot of the rest of Florida feels like it has changed a lot. And one of the reasons Sanibel hasn’t changed is because they have a very good growth-management plan, and two-thirds of the island is preserved.”

In 1976, Chauncey Goss’ father, Porter Goss, then Sanibel mayor and former director of the CIA, helped shepherd the Sanibel Plan, which put a cap on dwelling units to promote sustainable, harmonious living with Sanibel’s landscapes and wildlife.

In a revised version of the plan from 2013, officials wrote that the initial plan “marked a substantial departure from the preexisting Lee County zoning and development standards.”

If Sanibel followed Lee County rules, surely Ian’s wrath would have been worse; about 30,000 residential units would have been permitted with “virtually no environmental safeguards.” Instead, the plan reduced that figure by 75 percent to about 7,800 residential units.

Environmental preservation was always a top priority, but storm safety was, too. In the updated Sanibel plan, officials wrote: “It [the original Sanibel Plan] also developed new planning guidelines to reduce the potential threat to life, beaches and structures from hurricanes.”

Chauncey Goss said he was only about 7 or 8 years old when the Sanibel Plan was passed, so he does not remember the political battle. But he knows that it was one.

“It didn’t come easily,” Goss said. “And everything they worked for, they had to work for it.”

Despite his desire to rebuild and continue living on Sanibel, Goss recognizes the risks associated not only with hurricanes, but rising seas and other hazards associated with climate change.

“There’s always something in any paradise that’s dangerous. So, you just have to be aware of it and manage around it, and I think we can,” he said. “I don’t think it’s ‘Oh, you had a hurricane, now everybody needs to move to Colorado.’ It’s ‘Oh we had a hurricane, so let’s learn from that.’ And let’s see what we didn’t do well and what we did do well.”

Sanders, too, acknowledges the reality of climate change, and she is cognizant of its link with worsening hurricanes. She said she rejects the notion that Ian was, as some have put it, a “100-year storm.” She was born a year before Hurricane Donna, a Category 4 storm, barreled into Southwest Florida almost exactly 62 years before Ian.

“Our water is warmer,” she said. “We’re not getting Category 1 or Category 2 storms.”

Some people Sanders helped with cleanup ignore the science of climate change altogether.

“A lot of these older people, they’re not thinking climate change, or they’re in denial about it,” she said. “These people think, you know what, I’m 70-years-old, if I live another 10 years, I’ll be thankful, I’m not going to worry about it.”

Some younger residents, like 27-year-old Fort Myers native Joshua Huff, said Hurricane Ian is forcing a consideration of leaving the coast.

“I would love to get the hell out of here,” Huff said.

Time capsule, or time running out?

For Southwest Florida islanders deciding whether to stay, it’s uncertain whether Goss’s vision to maintain the vintage Florida “time capsule” can endure. Many small beach shops on Sanibel and at Fort Myers Beach were either destroyed or suffered too much damage to re-open. On the other hand, the massive Margaritaville Beach Resort that was underway in Fort Myers is on track to open at the end of this year. Company officials recently noted that “property values have grown post Ian, which is a very good indicator in the confidence of our recovery and future.” While the resort tries to market Edna Mae Surf Shop charm, it is a destination resort, one of dozens of locations, including landlocked Pigeon Forge and Gatlinburg, Tennessee.

On March 20th, a standing-room only crowd of citizens packed a joint session of the Town of Fort Myers Beach and the Local Land Planning Agency, some to protest higher density developments proposed for the town’s land-use plan. The town incorporated in part because “we did not want to have a bunch of high-rises on this island,” said lifetime resident Cassius Upton, who urged commissioners to stand up for middle-class residents who are trying to stay and not “big boy” developers.

Whatever the region’s future, said Sciaudone, the N.C. state engineering professor and barrier islands researcher, the key is that local people get involved in planning it. “It’s very important for the communities themselves to have a voice.”

Meanwhile Sanders and Goss both said they believe people rebuilding or considering moving to barrier islands should adopt a “buyer beware” mentality.

“You got to move knowing that climate change is here, these storms are nothing to play with,” Sanders said. “The potential for you to lose everything is going to be there.”

Living on the Edge

Living on the Edge