An entire town of Floridians abandoned their barrier island in the wake of a major hurricane in the nineteenth century. Historians urge us to remember their decision — but memory is a fickle thing.

To the fishermen plying the waters around the Cedar Keys, a string of barrier islands on Florida’s northern Gulf coast, the morning of September 28, 1896, revealed a sky both beautiful and strange.

“The sun was shining most of the time, but it seemed to shine like there was a heavy fog in front of it, and there was a terrible heat,” recalled veteran fisherman Nicodemus Wilder.

Unbeknownst to Wilder and his crew, and to the nearly 1,200 people living on the Cedar Keys, a massive hurricane was approaching. The storm had begun as a tropical depression south of Puerto Rico, then moved slowly up the Gulf of Mexico, biding time as it gathered strength.

The day ended with a brilliant red sunset, and an unnatural calm spread across the islands. On the little island of Atsena Otie, 10-year-old Velma Crevasse went to bed early with her family. Her father, a steamboat captain, expected to rise early to sail to Key West. Hours later, however, they were awakened by screaming winds as the hurricane slammed into the coast. Winds peaking at 125 miles an hour soon shattered the Crevasses’ front windows, forcing the family to huddle together in the back of the house. They listened for hours to the sounds of glass busting, wood rattling, and rain pouring in.

The winds died completely as the next morning dawned. The Crevasse family was shaken but unhurt. As her mother began to prepare breakfast, young Velma was sitting on the steps outside. Suddenly she ran into the kitchen, screaming, “Look at the water coming!”

A 10-foot storm surge coming off the hurricane’s back end was engulfing the island. The Crevasse family fled to their neighbor’s house, which stood three stories tall and on slightly higher ground. From the top floor, they looked below to see the water rise to the second story. They looked outside to see their own house wrenched off its foundations by the giant wave.

A resident of Way Key, the barrier island sitting closer inland, watched the devastation of Atsena Otie from his own second-story window. “A wall of foamy water came plunging over the town,” he later told a Jacksonville reporter. “Buildings went down like sticks.”

Fishermen like Wilder and 14-year-old William Delaino, a crew member on another vessel, were helplessly caught out on the water, also watching as the surge approached. “There was a mountain of water coming down on us,” Delaino recalled.

“Waves so high, it looked like a black wall coming at us, and it seemed there wasn’t any chance of us staying alive,” was Wilder’s testimony.

Somehow, both men lived. Wilder was swept out to sea but survived. Delaino’s boat sank but he swam free, clinging to broken tree limbs and other debris to stay afloat. He and many others, some living and some dead, washed ashore hours later as the storm moved inland.

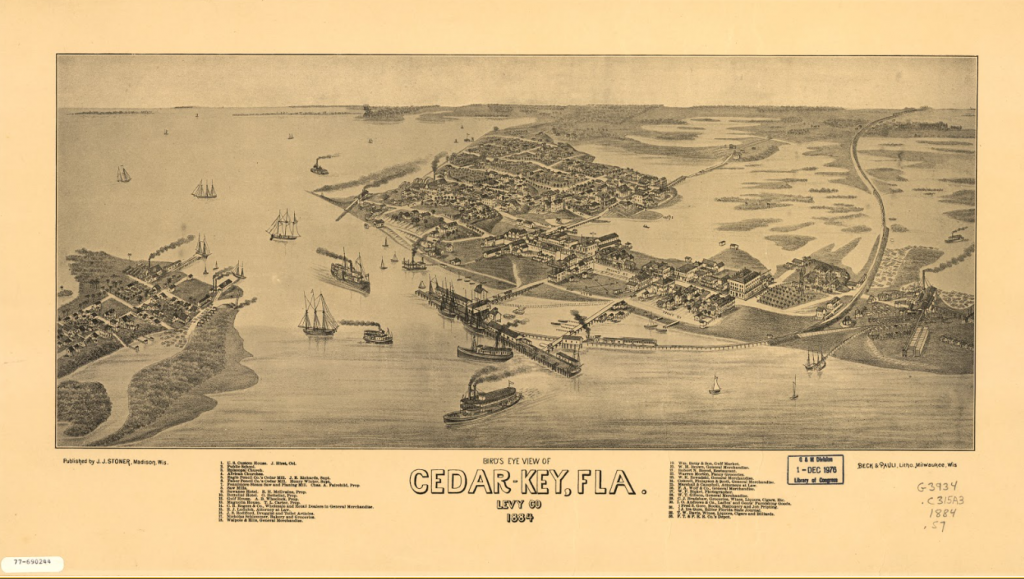

Across the Cedar Keys, more than 30 people died. Nearly all the 50 or so buildings on Atsena Otie were destroyed, including the town’s cedar mill where many of the residents earned their living. With no town left, most of them abandoned the island; the few who remained didn’t last there long. By 1910, the island had no human inhabitants. It remains that way today.

We can know the fury and devastation of the 1896 storm partly through the efforts of scholars like Ken Sassaman. An archaeologist at the University of Florida, Sassaman wants to recreate the 1896 hurricane on Atsena Otie for people today. He wants them to experience it almost as though they lived through it themselves — particularly if they’ve never experienced a hurricane before.

Climate change puts those living on barrier islands at risk of even stronger storms and deadlier storm surges. Yet many barrier islands continue to be developed. Coastal population is skyrocketing at even greater rates than Florida’s population in general as people flood into the disaster-prone state. Sassaman believes that if they were exposed to a powerful interpretation of a historic storm, one that killed people and destroyed homes and even drowned an industry, they might think twice about living on coastal outposts.

“People come in with no prior experience, no memory [of a hurricane],” he says. “But if they were actually educated about the long-term history of weather events that impacted that community, they might change their mind.”

Sassaman and his colleagues want to reconstruct the 1896 hurricane through a virtual reality experience. They hope to use archaeological, archival, geospatial and oral historical data to build the experience, so that people might don Oculus headsets and feel what it was like to be a Velma Crevasse or a William Delaino, at the mercy of a Category 3 hurricane. They would essentially be forming a memory of an event of which they had no bodily experience.

An implanted “hurricane memory,” as Sassaman calls it, could prevent humans from falling into common cognitive traps that may cause us to underestimate the long-term risk from hurricanes. For one, we tend to form memories of the past based on our most recent experiences, a phenomenon referred to as availability bias.

“If you went to Cedar Key today,” says Sassaman, “and you randomly selected 12 people on the street, and you said, hey, you’ve been living here all your life, right? OK, how bad do hurricanes get here? They’re not going to say 1896 or 1842, they’re going to be talking about the ones they lived through.”

That’s true even if those storms weren’t as bad.

“If people only have available to them what they’ve experienced,” he continues, “can we expand their experience virtually? Can we draw you into a world where the experiences of other people in other places and times will affect your vision of futures, your sense of what’s coming next?”

Humans also tend to assume that the further things are in the past, the less relevant they are to us now — an assumption endlessly frustrating to archaeologists like Sassaman, who believe that the past, no matter how ancient, holds valuable lessons for our future. Archaeology, in fact, can tell us many things about how past humans adapted to extreme weather and shifting climates, yet the discipline is unrepresented among the world’s coordinated efforts to fight climate change.

Of course, discouraging people from settling on barrier islands is not as easy as having them strap on a VR headset. Coastal waters provide livelihoods. They entice investors and developers, who in turn entice homebuyers with money and an unquenchable desire for oceanfront views. And despite all the newcomers, many coastal communities have deep roots. They are home to people whose “hurricane memory” is not simulated but very real.

Captain Kenny McCain is a fourth- or fifth-generation Cedar Keyan. He works for the University of Florida’s Nature Coast Biological Station and is well known around the small island. (Cedar Key is today’s town; its barrier island is officially known as Way Key.) He isn’t sure how many generations his family goes back, exactly — although he says that people keep wanting to add on local ancestors.

“I think the last time Dr. Payne [Jack Payne, a former executive of UF’s Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences] introduced me, it was 11 generations,” he jokes. “You know, we helped build the Earth at one time, but yeah, it’s four to five generations, maybe six.” Their roots on Cedar Key extend at least to the Civil War, according to his brother’s genealogy research.

McCain can walk the island and point to his cousin’s bait shop there, his grandmother’s old restaurant there, his mother’s house there. He and his wife live in the house his grandfather bought in 1944. It was blown off its foundation during 1950 Hurricane Easy, with the family sheltering inside at the time. Miraculously, they were unhurt.

For McCain and other multi-generation residents of Cedar Key, hurricanes are just a part of life. You keep your eye on them, you have your evacuation plan ready, you hope for the best, you pick up the pieces.

There’s muscle memory in how McCain describes the recovery process, which he and his family have undertaken many times. To tackle a flooded house, for example, “you go in there and you wash the house out. And a lot of these older houses, the sheetrock is at the four-foot level … You go in there and you cut that out, open up the walls, wash it out, dry it, put it back together, go again.”

Repairs can take as little as three or four days, “depending how energetic you are,” McCain says.

Despite the frequent threat from hurricanes, McCain can’t see himself living anywhere else. Most of his relatives have stayed on Cedar Key, including the new generation.

“I’ve seen a lot of nice places, neat places, but this is home,” he says. “A lot of it’s family. I got close family, I got friends [from] growing up.” He likes telling family stories, and he fondly recalls the big dinners his mother would cook. She would start cooking at nine every morning to have dinner on the table by noon, when his father — and usually several other relatives and friends — came in from work. (For them lunch was dinner, and dinner was supper.)

“It was fried chicken, lima beans, fried mullet, fried pork chops, you know? Every now and then baked chicken. And baked biscuits every day that she made from scratch.”

For McCain, it’s family memories, not hurricane memory, that matters more when it comes to making a home on a place like Cedar Key.

Perhaps more powerful than either type of memory, though, is money. Money is often the deciding factor in whether barrier islands get developed — or, in the case of Atsena Otie, whether they don’t.

The 1896 hurricane was the nail in the coffin for the cedar manufacturing industry on Way Key and Atsena Otie. Its days were already numbered: Most of the cedar forests had been decimated, and as soon as the trees ran out, so would the money. (There was no talk of reforestation at the time.) When the hurricane took out the town’s cedar mill, there was nothing much left for the residents. A handful of people stayed, outnumbered by cows. But by 1910 even they were gone.

Had the cedar industry still been going strong, Sassaman muses, more people would have stayed, rebuilt, continued logging trees and selling the wood.

As it was, Atsena Otie remained people-free until the late 1980s, when a proposal to develop the island into a residential community almost went through. There was local resistance to the idea, and for some, hurricane memory served.

“I doubt that anyone aware of the history of that piece of land and its devastation by past storms would entertain the idea of placing a residence there,” one local resident wrote in the Cedar Key Beacon in 1992. “Even on Way Key our exposure to storm hazard is already great enough to cause much worry; to increase that exposure by deliberately building in harm’s way would be a dangerous temptation of fate.”

In the end, though, it was the region’s burgeoning shellfish industry that helped save Atsena Otie. Shellfish farming relies on pristine, healthy waters, so that the harvests are safe for consumption. Developing Atsena Otie would reduce the water quality around the island, and with it, the area available for shellfish farming.

Bolstered by arguments for protecting the local wildlife and preserving Atsena Otie’s history, the case for keeping the island undeveloped won out: The Suwanee River Water Management District purchased Atsena Otie in 1997 for $3.1 million and turned it over to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to manage as part of the Cedar Keys National Wildlife Refuge.

“It was probably the biggest bargain in the state of Florida, for saving an environment,” says Cedar Key Vice-Mayor Sue Colson, who served on the water management district’s board at the time and “had the supreme pleasure of signing that document.”

Although the return on the investment in the shellfish industry was difficult to quantify, predictions of its profitability turned out to be correct. Cedar Key is now one of the top producers of clams in the country, and the top producer of oysters in the state. Flyers at the town’s welcome center tout both the environmental and economic benefits of clamming. Clams clean the water by filtering out excess sediment, which makes the water clearer and allows for seagrasses to grow, supporting other sea life. The clams remove excess nitrogen from the water and sequester planet-warming carbon dioxide. They perform, in other words, the same services as wastewater treatment plants and managed pine plantations. At the same time, they generate enough income to support much of Cedar Key’s population.

“This town is about money,” says Colson. “The clams are about money. It’s a way to make money. Fortunately, it’s a way to eat, too.”

Saving Atsena Otie from development played a key part in the shellfish industry’s success, she says. It shows a decision-making process typical of humans: Memory can be a powerful force. But it’s often the demands of the present, rather than the lessons of the past, that take precedence.

Living on the Edge

Living on the Edge